Steven J. Pyne is an emeritus professor at Arizona State University and the author of several books on fire history and policy. He wrote this opinion piece as a protest against the prevention and suppression of wildfires in our land management process. He argues that revising our perception of fire and accepting its presence in ecosystems is critical to our ongoing relationship with our planet.

He describes “a paradox at the core of Earth’s unraveling firescapes,” that “we have too many bad fires — fires that kill people, burn towns, and trash valued landscapes. We have too few good ones — fires that enhance ecological integrity and hold fires within their historic ranges” [Pyne 2020]. Operating under a paradigm of total fire suppression leads us astray in managing landscapes, while we so readily accept fire in the form of fossil fuel combustion in so much of our lives. Pyne sees these behaviors as evidence that our relationship with fire is out of whack.

He stresses the importance of distinguishing between burning in living ecosystems and burning the fossils of life from past ages.

The critical contrast lies in a deeper dialectic than burned and unburned landscapes. It is a dialectic between burning living biomass and burning fossil biomass. We are taking stuff out of the geologic past, burning it in the present with all kinds of little understood consequences, and passing the effluent into the geologic future.

…

Fires in living landscapes come with ecological checks and balances. Fires in lithic landscapes have no boundaries save those humans impose on themselves [Pyne 2020].

Pyne associates three paradoxes with our current fire policies. First, abandoning a traditional lore of “light burning” has removed good fires and left us with only bad and harmful ones. When controlled burns are not practiced regularly to manage landscapes, vegetation can build up and fuel the intensity and spread of uncontrolled blazes that spark.

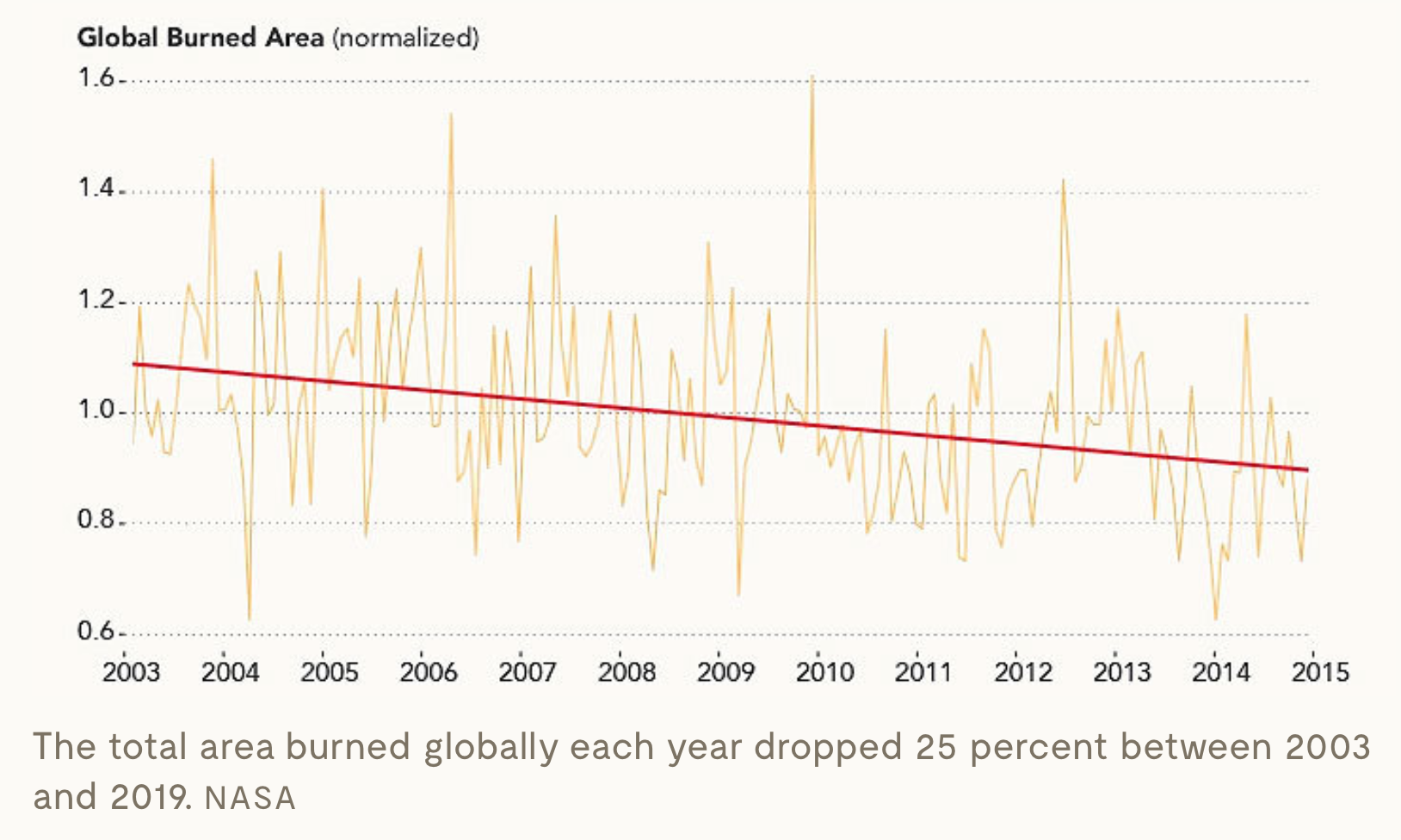

Second and surprisingly: “The Earth does not have more fire today than before fossil fuels emerged as a primary source of energy: It has significantly less” [Pyne 2020]. That is, the amount of land burned in fires has actually decreased, while the presence of intense “feral flames” has increased. The decrease in the scope of fire is largely due to the move away from fire’s use in agriculture and its replacement with modern techniques, including machinery powered by combustion. As Pyne describes,

Farmers had relied on fire to fertilize, fumigate, and alter microclimates. Fire did all this in one catalytic process that self-propagated. But with the transition to fossil biomass, modern agriculture found surrogates with artificial fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides, and it now had the fossil-fuel-powered machines to distribute them. Production became more efficient; transport, more dense. As agriculture joins a modern economy, working flames recede [Pyne 2020].

What we are left with is intense, destructive wildfire, rather than helpful working fire. Pyne points out that we now only see one half of fire’s possibilities, since the working fire shaping landscapes and agricultural systems is notably absent. He says: “Landscape fire fades; what fire persists tends to be outbreaks of feral fire. We see those oft-disastrous flames. We don’t see the lost fires or the sublimated fires in machines that removed them” [Pyne 2020].

The third paradox is that as we reduce our use of fossil fuels going forward (as one sort of fire), we will have a greater need “to manage fire in living landscapes.” So Pyne calls for us “to reinstate the right kind of fire, and … adapt to fire’s presence and let it do the work for us.” He pushes for the recognition that transitioning away from our reliance on fossil fuel burning is an important but incomplete step in balancing ecosystem health. Fires in living systems have an important role to play, and according to Pyne, “the need is not just to reduce fuels to help contain wildfires; those missing fires did biological work for which no single surrogate exists” [Pyne 2020]. He asserts that we will need to reintroduce fire as a staple tool on our landscapes.

|

Fires in living systems have an important role to play, and according to Pyne, “the need is not just to reduce fuels to help contain wildfires; those missing fires did biological work for which no single surrogate exists.” He asserts that we will need to reintroduce fire as a staple tool on our landscapes. |

Pyne concludes with a call for the overhaul of our conceptual and policy treatment of fire.

Anthropogenic fire needs more room to maneuver – more geographic space, more legal space, more political space, more conceptual space. … Equally, society needs to rethink liability law to reduce the risks incurred by fire officers doing a necessary job …; adapt air quality regulations …; and tweak National Environmental Policy Act review processes … [to] accommodate the realities of restored fire at a landscape scale. … Communities in the fire equivalents of floodplains need hardening [Pyne 2020].

He proposes that fire restoration jobs can replace those lost from forestry and fire suppression. He admits that our understanding of fire biology requires more research, and that our greatest need is for “a working fire culture … that ensures fire’s proper place in the landscape” by renewing “our ancient alliance” with fire and making it “an indispensable friend.”

Pyne, Stephan, 2020, Our Burning Planet: Why We Must Learn to Live With Fire, Yale Environment 360, https://e360.yale.edu/features/our-burning-planet-why-we-must-learn-to-live-with-fire.