What animal is the “Superhero of the Desert,” reshaping entire ecosystems simply by eating, roaming, and . . . pooping?

Meet the Desert Superhero!

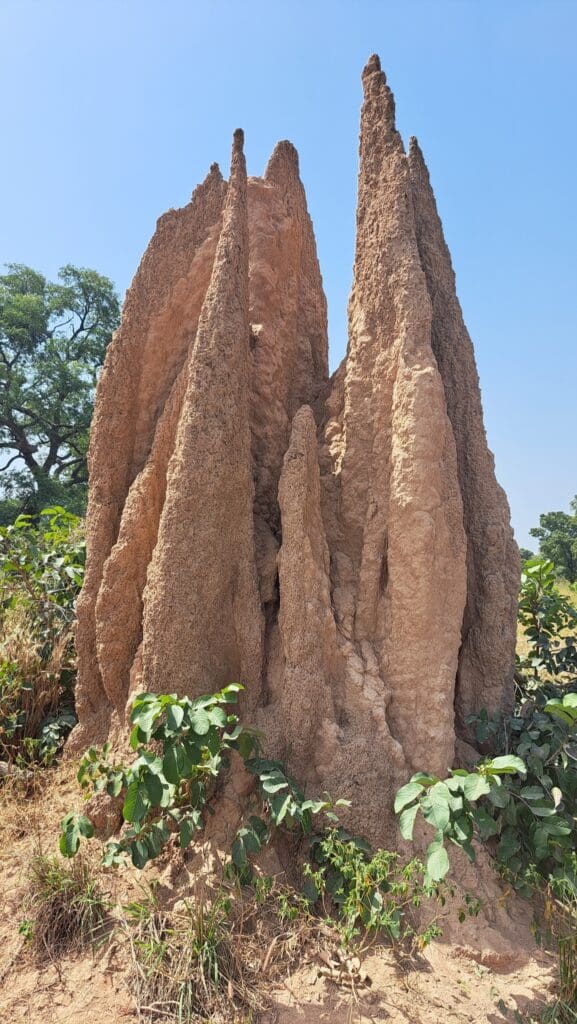

Image credit: Houman Doroudi via iNaturalist (CC-BY-NC)

Desert wanderer

Curved as the dunes he walks on

Splat! Anger expressed

A close family friend asked me to cover camels as one of my Featured Creatures. Ask, and ye shall receive! Despite the majority of camels today being domesticated species, they still play important roles in their local ecosystem, and contribute to the biodiversity of the habitats in which they live.

Dominating the Desert, and De-bunking Assumptions

Camels are far more than the four-legged, desert pack animals typically shown in movies—their presence shapes the health, stability, and biodiversity of their ecosystems. Their grazing patterns, movement, digestion, and remarkable resilience collectively engineer the landscapes they inhabit.

Camels haven’t just adapted to desert life, their entire bodies are designed for endurance in some of the most unforgiving climates on Earth. Did you know they can go up to 10 days without drinking, even in extreme heat! Their long legs help keep them cool, elevating their bodies away from ground temperatures that can reach 158ºF (70°C), and their thick coat insulates them against radiant heat. In the summer, their coats lighten to reflect the sunlight.

Long eyelashes, ear hairs, and sealable nostrils protect against the blowing sand, while their wide, padded feet keep them from sinking into the desert sand or snow. Bactrian camels grow heavy winter coats that enable survival in winter temperatures (-20ºF [-29ºC]), then shed them to adapt to the hot summer temperatures. Their mouths have a thick, leathery lining that allows them to chew thorny, salty vegetation, with split, mobile upper lips that help them grasp sparse grasses . . . and spit. Well, sorta. . .

Desert Engineers and Seed Dispersers

These “ships of the desert” feed on thorny, salty, dry plants that most herbivores avoid, keeping dominant species in check and promoting plant diversity. Their nomadic lifestyle prevents overgrazing, spreading this balancing effect across vast ranges and reducing the risk of desertification. As they move, they disperse seeds in their dung, enriching poor soils with nutrients and enabling new vegetation to take hold where it otherwise could not.

Even their hydration strategy—relying heavily on moisture from plants and drinking only occasionally—protects scarce water sources that smaller species depend on. Trails they create become pathways for other wildlife, while their presence attracts predators and scavengers, helping sustain food webs in seemingly barren terrain.

People often assume that camels carry water in their humps and spit when they are annoyed. But those humps aren’t sloshing with water. They are fat-storage structures that provide a slow-burning energy reserve when food is scarce. And that spitting? It’s actually a warning system composed of both saliva and partially digested stomach contents.

Helping People and Ecosystems Endure

Even though they may look goofy at first, the ecological and cultural value of the camel is extraordinary.

They have supported human survival in harsh environments for thousands of years. Domesticated camels provide wool, meat, milk, transportation, and labor. Their endurance and strength have made them central to trade routes, cultural traditions, and economic activity across regions where few other animals could thrive.

Camels shape vegetation patterns, support biodiversity, stabilize fragile ecosystems, and enable life in regions that would otherwise be nearly uninhabitable. Without camels, many desert landscapes would lose the very processes that sustain them.

So next time you see a camel, in a movie, at a zoo, or on your travels, remember that these are no ordinary creatures. They are survival specialists and a cornerstone of some of the world’s harshest and most remarkable environments.

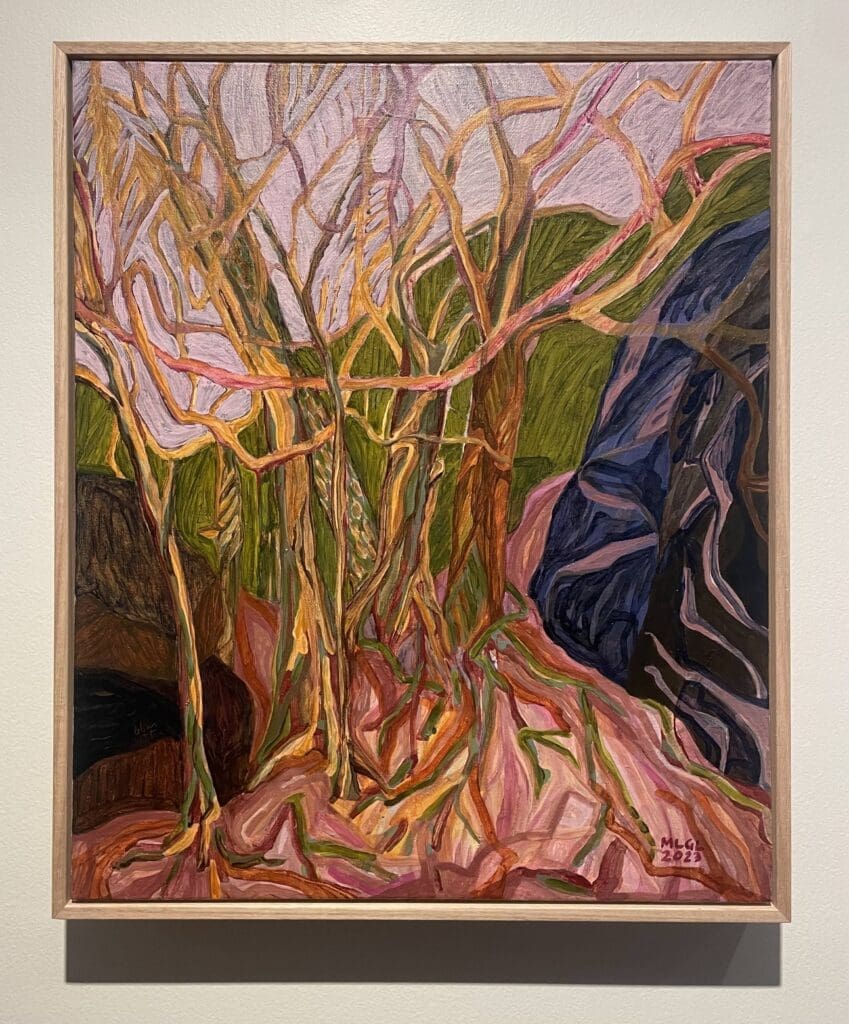

photographed in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert.

Image credit: Chris Scharf, a client of Royle Safaris via iNaturalist (CC-BY-NC)

Sienna Weinstein is a wildlife photographer, zoologist, and lifelong advocate for the conservation of wildlife across the globe. She earned her B.S. in Zoology from the University of Vermont, followed by a M.S. degree in Environmental Studies with a concentration in Conservation Biology from Antioch University New England. While earning her Bachelor’s degree, Sienna participated in a study abroad program in South Africa and Eswatini (formerly Swaziland), taking part in fieldwork involving species abundance and diversity in the southern African ecosystem. She is also an official member of the Upsilon Tau chapter of the Beta Beta Beta National Biological Honor Society.

Deciding at the end of her academic career that she wanted to grow her natural creativity and hobby of photography into something more, Sienna dedicated herself to the field of wildlife conservation communication as a means to promote the conservation of wildlife. Her photography has been credited by organizations including The Nature Conservancy, Zoo New England, and the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. She was also an invited reviewer of an elephant ethology lesson plan for Picture Perfect STEM Lessons (May 2017) by NSTA Press. Along with writing for Bio4Climate, she is also a volunteer writer for the New England Primate Conservancy. In her free time, she enjoys playing video games, watching wildlife documentaries, photographing nature and wildlife, and posting her work on her LinkedIn profile. She hopes to create a more professional portfolio in the near future.

Dig Deeper

• https://animals.sandiegozoo.org/animals/camel

• https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camel

• https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wild_Bactrian_camel

• https://kimd.org/the-role-of-camels-in-desert-ecosystems/

• https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/how-many-types-of-camels-live-in-the-world-today.html

• https://www.zsl.org/news-and-events/news/wild-bactrian-camel-research