What plant thrives in the harshest landscapes, conserving water like a desert camel, and produces a sweet yet spiky fruit enjoyed for centuries? The Prickly Pear Cactus!

When I’m in the south of France, nothing makes me happier than spending the day by the ocean, taking in the salty breeze and strolling along the littoral. After a long afternoon on the beach, as I make my way home, I always notice prickly pear cacti scattered throughout the local fauna.

Prickly pear cacti are everywhere in the south of France, where I’m from. My mom, who grew up in Corsica, used to tell me stories about how she’d collect and eat the fruit as a kid. So, naturally, last summer, when I spotted some growing along the path home from the beach, I figured—why not try one myself?

Big mistake.

Without gloves (rookie move), I grabbed one with my bare hands. The next 20 minutes were spent with my friends painstakingly plucking hundreds of tiny, nearly invisible needles out of my fingertips. The pain wasn’t unbearable, but watching my hands transform into a pincushion was… unsettling. And to top it all off? The fruit wasn’t even ripe.

For the longest time, I just assumed prickly pears were native to the Mediterranean. They grow everywhere, you can buy them at local markets, and my mom spoke about them like they were an age-old Corsican tradition. But a few weeks ago, while researching cochineal bugs (parasitic insects that live on prickly pear cacti), I discovered something surprising—prickly pears aren’t native to the south of France at all. They actually originate from Central and South America, and were introduced to the Mediterranean from the Americas centuries ago. They’ve since become naturalized.

Curious to learn more, I dove into the biology of prickly pears—and it turns out, these cacti are far more than just a tasty (and slightly dangerous) snack. Their survival strategies, adaptations, and ecological impact make them one of the most fascinating plants out there.

Credit: Maciej Cisowski via Pexels

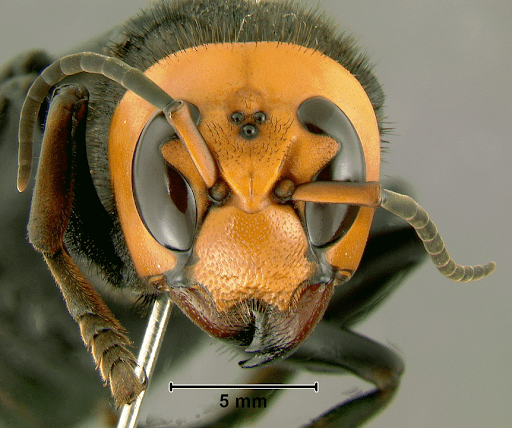

Prickly pear cacti belong to the Cactaceae family, and they’re absolute survivors. In spring and summer, they produce vibrant flowers that bloom directly on their paddles, eventually transforming into edible berries covered in sneaky little thorns (trust me, I learned that the hard way).

These cacti thrive in drylands but adapt surprisingly well to different climates. They prefer warm summers, cool dry winters, and temperatures above -5°C (23°F).Their ability to store water efficiently and withstand long dry periods has earned them the nickname ‘the camel of the plant world.’ They can lose up to 80-90% of their total water content and still bounce back, an adaptation that allows them to endure long periods of drought.

They are designed to make the most of their access to water whenever they get the chance. The cactus can develop different types of roots depending on what they need to survive, making them masters of adaptation. One of their coolest tricks? “Rain roots.” These special roots pop up within hours of light rainfall to soak up water—then vanish once the soil dries out.

And then there are their infamous spines. Prickly pears have two kinds: large protective spines and tiny, hair-like glochids. The glochids are the real troublemakers—easily dislodged, nearly invisible, and an absolute nightmare to remove if they get stuck in your skin. (Again, learned this the hard way.)

Nopal (Cactus Pads) – A Nutrient Powerhouse

The term “nopal” refers to both the prickly pear cactus and its pads. It originates from the Nahuatl word nohpalli, which specifically describes the plant’s flat, fleshy segments.

These pads are highly nutritious and well-suited for human consumption, packed with essential vitamins and minerals. They are especially rich in calcium, making them an excellent dietary alternative for populations with high rates of lactose intolerance, such as in India.

Beyond calcium, nopales also provide amino acids and protein, offering a valuable plant-based protein source. They are rich in fiber, vitamins, and minerals, making their nutritional profile comparable to fruits like apples and oranges, explaining their long-standing role in traditional cuisine. From soups and stews to salads and marmalades, they are a versatile ingredient enjoyed in a variety of dishes

Ever wondered how to clean and grill a prickly pear pad at home?

The Fruit – Sweet & Versatile

Prickly pears produce colorful, juicy fruits called tunas, which range in color from white and yellow to deep red and orange as they ripen. Their flavor is often described as a mix between watermelon and berries, while others compare it to pomegranate. Either way, they make for a delicious and refreshing snack.

But before you take a bite, be sure to peel them carefully. If you don’t remove the outer layer properly, you might end up with tiny spines lodged in your lips, tongue, and throat (which is about as fun as it sounds). Once cleaned, the fruit is used in jams, juices, and is even pickled!

Prickly pear cacti produce stunning flowers that attract a variety of pollinators, particularly bees. Some specialist pollinators have evolved to depend exclusively on prickly pear flowers as their sole pollen source, highlighting an amazing co-evolutionary relationship. One fascinating example is a variety that has evolved to be pollinated exclusively by hummingbirds, demonstrating the plant’s remarkable ecological flexibility.

If you’d like to see this incredible interaction for yourself, check out the following footage of a hummingbird feeding on a prickly pear flower. Though the video quality is low, the enthusiasm of the couple filming it makes up for it! 🙂

Another fascinating feature of prickly pear flowers are their thermotactic anthers. Okay so yeah, that’s a bit of a mouthful. Basically, the part of the flower responsible for producing pollen, the anthers, have a unique ability to respond to temperature changes—releasing pollen only when conditions are just right for pollination. Prickly pear flowers achieve this through movement; the anthers physically curl over to deposit pollen directly onto visiting pollinators.

You can even see this in action yourself! Try gently tapping an open flower, and watch as it instinctively delivers its pollen like a built-in pollen delivery system.

Once pollinated, the flowers transform into fruit, which then serve as an essential food source for birds and small mammals. These animals help disperse the seeds, allowing new cacti to grow in different areas. But prickly pears don’t just rely on seeds for reproduction, they also have an incredible ability to clone themselves. If a pad breaks off and lands in the right conditions, it can root itself and grow into an entirely new cactus. Talk about resilience!

Like most cacti, prickly pears are tough survivors, thriving even in degraded landscapes. But they go a step further, not just enduring harsh conditions, but actively helping to restore them. The plant’s roots act as natural barriers, preventing erosion, locking in moisture, and enriching the soil with organic matter. Studies show that areas dense with prickly pears experience significantly less soil degradation, proving their role in restoring fragile land.

They also improve soil structure, making it lighter and more fertile, which boosts microbial activity and essential nutrients. They act as natural detoxifiers, absorbing pollutants like heavy metals and petroleum-based toxins and offering an eco-friendly way to restore contaminated soils.

Credit: Homrani Bakali, Abdelmonaim, et. al, 2016

A Tale of Two Ecosystems

Prickly pear plantations are powerful carbon sinks, pulling CO₂ from the air and storing it in the soil. In fact, research shows that prickly pear cultivations in Mexico sequester carbon at rates comparable to forests. A major factor? The cactus stimulates microbial activity in the soil, a key driver of carbon storage.

When farmed sustainably, the CO₂ prickly pears absorb offset the greenhouse gases emitted during cultivation.

Prickly pear cacti have immense capability for land restoration and carbon sequestration, but this potential varies dramatically depending on how they are introduced and managed, and where. In some regions, like Ethiopia, they serve as a lifeline for communities facing desertification. In others, like South Africa, they’ve become invasive, disrupting native ecosystems.

By exploring these two contrasting case studies, we can see how the same plant can either heal or harm the land—and why responsible management is key.

Tigray, Ethiopia: A Natural Fit for Harsh Climates

In Ethiopia, where over half the land experiences water shortages, the prickly pear cactus has become indispensable since its introduction in the 19th century. Arid lands are notorious for unpredictable rainfall, prolonged droughts, and poor soils. But the prickly pear cactus defies these challenges. Requiring minimal water, it provides a reliable food source for both humans and animals, making it an essential crop for small-scale farmers in dry regions.

Prickly pear pads are a crucial livestock feed during droughts, providing moisture and nutrients when other forage is scarce. While it cannot be used as the sole source of nutrition for most ruminants, it’s definitely a necessary supplement in times of drought.

Additionally, the plant’s dense growth creates natural barriers, curbing overgrazing and helping native vegetation recover.

As a food source, prickly pear can be used to supplement human diet. The cactus is an alternative to water-intensive cereals like wheat and barley. With higher biomass yields and significantly lower water requirements, it offers a sustainable solution to food security in drought-prone areas.

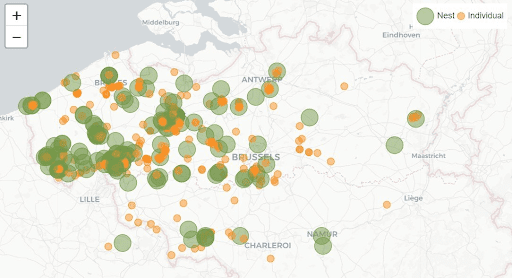

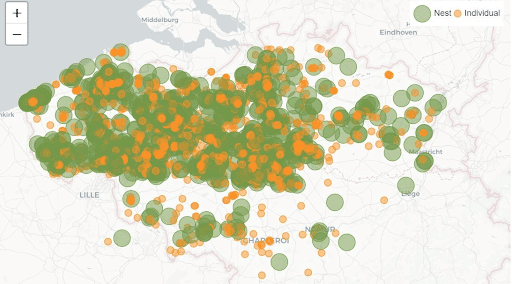

Unfortunately, prickly pear cultivation in Ethiopia is under threat from invasive cochineal infestations. These cochineal insects, originally used for dye production, were later introduced outside their native range, where they’ve become agricultural pests, devastating cactus populations.

Credit: tjeerddw (CC-BY-NC)

Credit: Toxmace (CC-BY-NC)

South Africa: When Prickly Pear Becomes a Problem

While the cactus is a valuable resource in some regions, in others, it becomes an invasive species, altering ecosystems and threatening native plants.

In South Africa, prickly pears were introduced by European settlers, but without natural predators to control them, they spread aggressively. Today, they dominate large areas, outcompeting native vegetation and consuming scarce resources like water and soil nutrients. Their dense growth also creates impenetrable thickets that hinder livestock grazing and disrupt local ecosystems.

To control its spread, South Africa turned to biological solutions, ironically using the same cochineal insect that threatens Ethiopia’s prickly pear. In South Africa, cochineal insects have been highly effective at curbing cactus overgrowth, selectively feeding on the invasive species and allowing native plants to recover.

This dual role of the prickly pear cactus—as both a valuable resource and a potential ecological threat—highlights the importance of responsible management. Striking a balance between conservation and cultivation is key to harnessing the plant’s benefits while preventing unintended environmental consequences.

Innovative Uses: From Energy to Eco-Friendly Materials

The prickly pear’s resilience extends beyond its survival in harsh environments—it’s also fueling innovation in sustainability. Scientists and entrepreneurs are finding new ways to harness this plant’s potential, from renewable energy to eco-friendly materials.

In the search for cleaner energy sources, prickly pear biomass is being used to produce biogas and bioethanol, offering a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Unlike resource-intensive crops, the cactus thrives with minimal water, making it a low-impact solution for sustainable energy. Meanwhile, its juice is being explored as a base for biodegradable plastics. Unlike corn-based bioplastics, which require significant land and water resources, cactus-based plastics are more sustainable and continue growing after harvesting, reducing environmental strain.

Cactus leather, developed by companies like Desserto, provides a sustainable alternative to synthetic and animal-based materials. Unlike traditional vegan leather, which often contains petroleum-based plastics, cactus leather is biodegradable, water-efficient, and durable. As more industries embrace the potential of this remarkable plant, the prickly pear is proving that sustainability and innovation can go hand in hand.

From nourishing communities to restoring degraded land, and generating clean energy, the prickly pear is far more than just a desert plant—it’s a symbol of resilience, innovation, and sustainability. However, its impact depends on careful management. Whether cultivated as a food source or controlled as an invasive species, striking the right balance is key to unlocking its full potential.

And if this article has inspired you to try a prickly pear fruit for yourself, please stick to the store-bought varieties. Unlike wild varieties, cultivated prickly pears are often spineless, making them easier (and safer) to eat. Plus, it would give me, the author, peace of mind knowing that no one has to suffer the same fate I did when I ended up with a hand full of spines after an ill-fated foraging attempt.

Lakhena Park holds degrees in Public Policy and Human Rights Law but has recently shifted her focus toward sustainability, ecosystem restoration, and regenerative agriculture. Passionate about reshaping food systems, she explores how agroecology and land management practices can restore biodiversity, improve soil health, and build resilient communities. She is currently preparing to pursue a Permaculture Design Certificate (PDC) to deepen her understanding of regenerative practices. Fun fact: Pigs are her favorite farm animal—smart, playful, and excellent at turning soil, they embody everything she loves about regenerative farming.

Sources and Further Reading

- Agricultural Extension, Somervell County. (2015). Prickly pear biology and management. Texas A&M AgriLife Extension.

- Carbon Cactus Foundation. (n.d.). Carbon sequestration using Opuntia cactus

- Kumar, K. (2018). Introduction of carmine cochineal to Northern Ethiopia: Current status of infestation on cactus pear and control measures. ResearchGate.

- Kumar, K. (2018). Cactus pear cultivation and uses. ResearchGate.

- Rhodes University. (n.d.). Mass rearing of biocontrol agents at the Kareiga Uitenhage mass rearing facility. Centre for Biological Control.

- ScienceDirect. (2022). The role of prickly pear in the ecological restoration process.

- Snowden, S. (2019, July 14). Scientist in Mexico creates biodegradable plastic from prickly pear cactus. Forbes.

- Something Over Tea. (2018, October 9). Cochineal insects: A tale of two imports.

- Springer. (2024). Prickly pear cochineal and carmine production. Springer Link..

- Sustainable Jungle. (2021). Cactus leather: A sustainable alternative to traditional materials

- Tacinga. (2013). The hummingbird-pollinated prickly pear. ResearchGate.

- Texas A&M AgriLife Extension. (2015). Prickly pear biology and management. Somervell County Extension Office.

- Texas Beyond History. (n.d.). Prickly pear in coastal Texas. Texas Beyond History.

- (2023). Cultivation of Opuntia ficus indica under biofuel production conditions.

- Wiley Online Library. (2019). Prickly pear cochineal (Dactylopius coccus) and carmine production. BES Journals.

- (2023). Potential for biofuels from prickly pear biomass.(n.d.). Prickly pear cactus for biogas production. Anaerobic Digestion Blog.