What acrobatic raptor was so essential to medieval public health, killing it was a crime and it became the national bird of Wales?

The red kite (Milvus milvus)!

Nature really thinks of everything.

I was back on my run through Madrid’s Casa de Campo, the 4,257 acre public park and preserve where I found Feature Creature inspiration in the form of a sickly hare a few weeks ago. After spending several minutes observing the hare, I continued as my run opened into a large clearing. A cinematic scene rolled out before me, as a red kite (milvus milvus), one of the hare’s natural predators, dropped out of an umbrella pine and flew off before me.

Maybe it was just my own naivety, but it was a special moment for me. You see, I’d run the park many times before, but rarely looked any further than the trail in front of me. Instead, this time I tried to pay attention to the web of life around me, and how each strand of it, living or not, connected with the others around it.

Take that red kite. It is an animal that works in service of its environment with a body and design that, in turn, work in near perfect service of it.

Nature’s cleanup crew

The red kite’s nesting range stretches in a broad band from the southern corner of Portugal, up through the Iberian Peninsula, central France, and Germany, before reaching the Baltic states. Smaller populations are also found in Mediterranean islands, coastal Italy, and the British Isles, where reintroduction campaigns in the 1980’s successfully revived its numbers.

They prefer to nest at the edge of woodlands, enabling quick and easy access to the open sky and landscape, not unlike how I look for an apartment within walking distance to the metro, or how a commuter in the suburbs might prefer to live a short drive from a highway or major thoroughfare on ramp. But wherever the red kite calls home, it has an important job to do.

The red kite is, first and foremost, a scavenger. Its diet consists primarily of carrion—dead animals, often livestock and game. By feeding on these carcasses, the red kite acts as a natural janitor and ultimately helps recycle nutrients back into the soil and surrounding environment.

When a scavenger like the red kite feasts on a dead animal, it kickstarts nature’s process for removing a carcass from (or to!) the environment. In feeding, they speed up the process of decomposition by physically breaking down the body and handing off a more manageable scene to smaller organisms like insects, bacteria, and fungi.

These insects and microbes release nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon into the soil as they break down the red kite’s leftovers. These nutrients enrich the soil, promoting plant growth, supporting other forms of life in the ecosystem, and maintaining essential geosystems.

Sarah W. Keenan, et al.

It’s humbling. What seems brutal or grotesque—feasting on dead animals—is really an elegant solution from nature to each life’s inevitable end.

Plasticity

While foraged carrion can make up the majority of the red kite’s diet (upwards of 75%), it is also an agile and capable hunter of hares, birds, rodents, and lizards, respectably quick prey in their own right. A deeply forked tail acts like a rudder, providing precision flight control when on the hunt.

Stephen Noulta (CC via Pexels)

This remarkable agility serves another purpose: communication. The red kite pairs a variety of unique vocalizations with striking physical displays, especially during courtship. And man, on that front does it deliver. It’s as if, in a bid to outdo the more visually aesthetic displays of other birds like parrots and peacocks, the red kite said, “alright, I see your colorful feathers and raise you tandem, spiraling corkscrew dives.” It’s worth taking a few seconds to watch.

This is all to say that the red kite is well-equipped to meet the demands of its environment, whether foraging or hunting. They have been observed changing their foraging behavior and diet based on food availability and changing environmental conditions. While this level of flexibility, or plasticity, is found among other raptors, what makes the red kite stand out in this regard is its success adapting to both rural and increasingly urbanized environments.

A connected, complicated story

It’s difficult to tell the story of the red kite without understanding the species’ relationship with us, with humans.

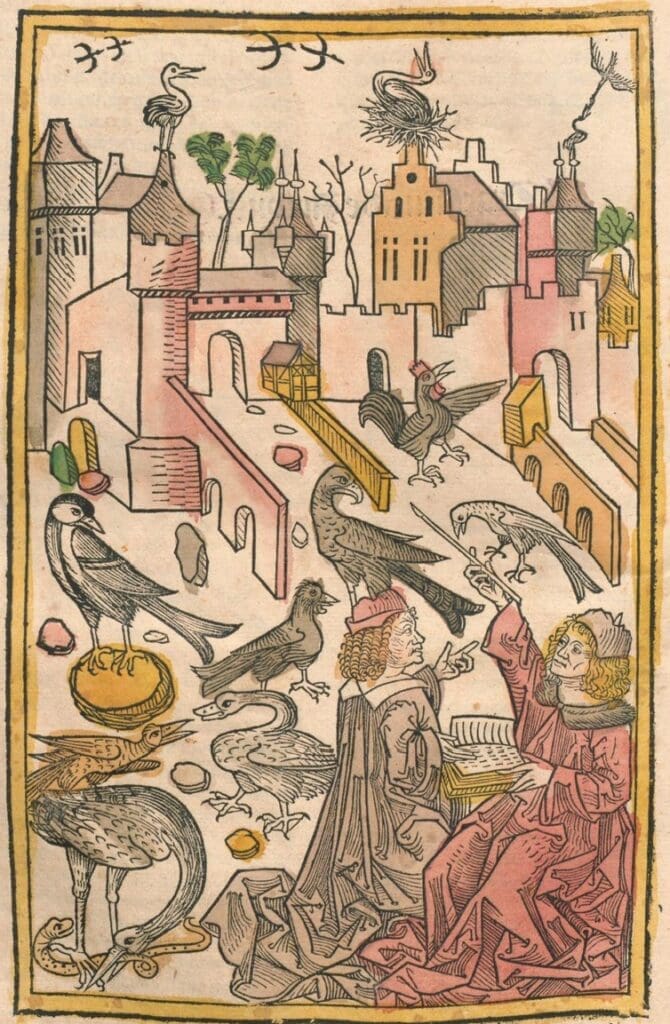

A natural & social scavenger, the red kite’s role in our story goes back almost as long as we’ve been hunting, practicing agriculture, and leaving waste in the streets. Our complex relationship spans centuries and reflects our evolving attitudes toward wildlife, shifting dynamics of human environments, and the species’ own plasticity. In the middle ages, the red kite was a common sight in European cities, and especially London, where it acted as a natural street cleaner, scavenging for scraps and waste in the then-squalid streets. In fact, it was protected by law, and harming one was a punishable offense, as its presence was crucial to maintaining urban sanitation.

Bredfield Wildlife Friendly Village

Attitudes began to shift however as human settlements expanded and agricultural practices intensified. The birds came to be seen as vermin, threatening livestock and hunting game populations. This, combined with a broader adoption of poison to control other animals like foxes, led to a dramatic decline in red kite populations. By the turn of the 20th century, the red kite had been pushed to near extinction in many parts of Europe. As few as a handful of pairs were believed to have survived in remote parts of Wales.

But as part of larger, global conservation trends, red kite reintroduction programs took off in the 1980’s, particularly in the UK. These efforts were successful, with Royal Society for the Protection of Birds operations director Jeff Knott declaring that it “might be the biggest species success story in UK conservation history.”

As I’ve come to understand it, this recovery is not so much the end of a story, but the beginning of a new, equally complicated chapter in Europe’s story with the red kite. Bird populations have rebounded, and are now learning how to live in a densely populated, 21st century world. Ever the survivors, red kites are adapting to modern urban and semi-urban environments. In southern England, they’ve once again become a common sight, soaring over towns and cities as they did hundreds of years ago, and foraging for food in suburban gardens.

bitsandbugs (CC via iNaturalist)

Raised on a steady diet of Planet Earth, Animal Planet, and Nat Geo, I think it was easy to see “nature” as a separate thing we’re siloed off from in our built environments, something wonderful and to be safeguarded in a separate place, something we can enter and exit at our leisure. It’s evident even in the way we collectively discuss it. We talk about “being out in nature,” “escaping to the outdoors,” “getting away from it all.”

And sometimes it takes a bird like the red kite to remind you that nature doesn’t exist separately from us. The red kite doesn’t necessarily see the Iberian savannah as any more or less wild than a British village. Where there is any life, there is an ecosystem.

Running to catch the next creature,

Brendan

Brendan Kelly began his career teaching conservation education programs at the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium. He is interested in how the intersection of informal education, mass communications and marketing can be retooled to drive relatable, accessible climate action. While he loves all ecosystems equally, he is admittedly partial to those in the alpine.

Sources and Further Reading:

- Movements of the Red Kite

- Red kite Milvus milvus, Scottish Wildlife Trust

- Red Kite (Milvus milvus), Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- RAPTORS a field guide for surveys and monitoring, John Hardey

- Breeding biology, behaviour, diet and conservation of the red kite (Milvus milvus), with particular emphasis on Mediterranean populations, François Mougeot, et al. 2011

- VULTURES AND LIVESTOCK