What animal travels over 100 miles for food and, due to warming temperatures, is suffering from insomnia?

The Black Bear!

Observing the scene from a large boulder at the water’s edge, the silence is disrupted by a faint clanging in the bushes as an unnatural rustling sounds from my campsite. Enraptured by the unfurling of clouds across the jagged landscape, I don’t see the creature until it emerges from a cluster of pines, pattering along a neighboring stretch of bedrock. The Black Bear is only 20 feet away when it dips into the water, head bobbing as the creature paddles to the other side of the lake. When it reaches the opposing shore, I release a breath I didn’t know I was holding, and watch as it pulls itself out of the water and crawls onto the green grass. The bear blends in with the darkness and disappears into the night.

It was the last night of a seven-day backpacking trip in Kings Canyon National Park in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California. We were staying at a campsite by Emerald Lake. After the bear encounter, I later returned to my campsite, only to find my bear barrels, designed to securely store food and other smellable items, scattered about – a reminder of the bear’s presence, and the complicated relationship between our species.

The Black Bear, also known as the American Black Bear, is found throughout North America, from the rugged Arctic regions of Alaska and Canada to parts of northern Mexico. In search of food, these creatures will travel up to 100 miles outside their territories, with their food availability often differing depending on the season. As omnivores, Black Bears consume both plants and other animals. Black bears help the growth of plants, such as berries, because the seeds are able to exit their digestive track and germinate – with the added benefit of fertile soil.

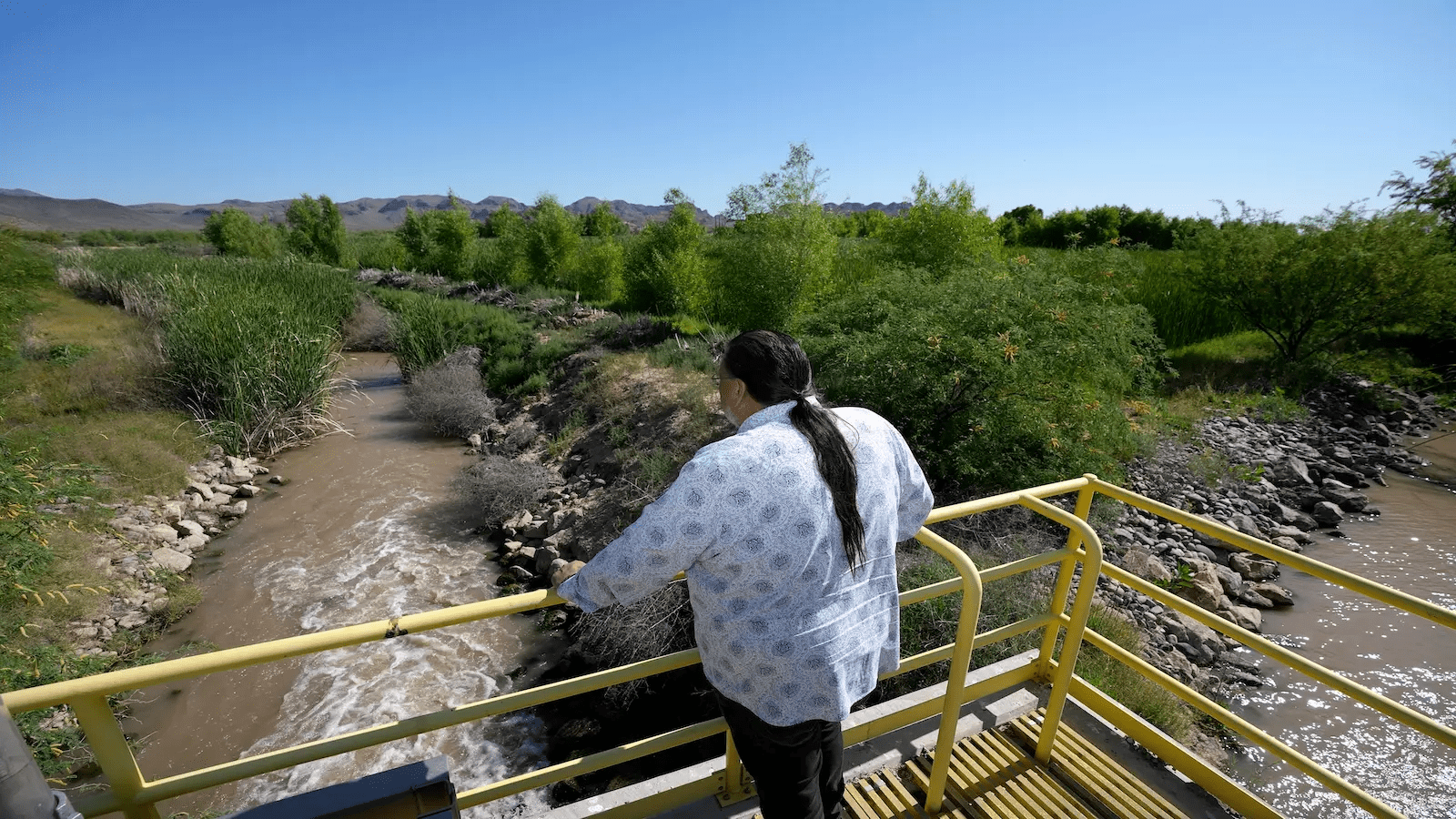

In the Pacific Northwest, Black Bears are well-known for their consumption of salmon. After catching and consuming salmon, Black Bears will often leave the carcasses at the edges of the stream or river, in an area known as the riparian zone. The salmon release nitrogen into the soil, which is then absorbed by large plant species. There is evidence that the nutrients from the salmon, created as a result of their predator-prey relationship with Black Bears, increase the overall health and well-being of the forest ecosystems in these areas.

In many areas, Black Bear food availability is being impacted by climate change. Recently, a group of researchers from the University of Nevada, Reno aimed to better understand how bear behavior has changed over time, especially the tension between human centers and Black Bear habitats. The group found that temperature swings in the early spring are devastating Black Bear food supply, resulting in bears seeking out food sources in human-centered areas. According to Dr. Kelley Stewart, who is leading the project, “The plants start growing and flowering with an early spring warm-up, and then there’s a late-season frost that takes them all out. It especially affects berries and the harder things like acorns, pine nuts and other things that nature normally provides for bears.” This decrease in food supply is leading to another negative outcome: Black Bears entering human settlements in search of food.

With increased human-bear interactions, bear mortality rises. While in part a result of lacking food resources, scavenging in human-dominated areas can result in the bears getting hit by cars or being euthanized. In June of 2024, Sierra County, California reported the first Black Bear-caused human mortality in recorded California history. Researchers have connected late frosts in early spring causing twice as many lethal removals of Black Bears compared to years without these cold snaps. When bears seek out the food of humans, they get used to trash and other attractants as a viable food source, therefore increasing their proximity to human centers. When bears become habituated to these environments, and human food, they are often labelled as “dangerous” and are euthanized.

There are communities working to repair this relationship between Black Bears and human-occupied places. The Boulder Bear Coalition was founded in 2014 and aims to educate the Boulder, Colorado residents on “proactively reducing attractants and enhancing deterrents.” Their methods focus on targeting the root of the issue, such as securing trash and providing resources so residents can implement strategies that keep bears and people safe. But the question remains that if Black Bears are seeking out human food in response to limited sustenance availability, do these actions solve the fundamental problem of our changing climate?

Climate change not only threatens Black Bear food supplies, but also their hibernation patterns. During the winter, Black Bears enter a state of decreased heart rate and dormancy known as hibernation, which is a response to colder temperatures. In preparation for hibernation, bears partake in excessive eating habits, otherwise known as hyperphagia. This increase in food intake helps build up body mass for the long winter months. However, with warming winters, bears are not sleeping for as long as they used to. According to a recent study, the length of bear hibernation could decrease by 19 to 39 days by 2050. With a shorter hibernation period, Black Bears will be threatened by limited food supply during the winter months. Which only becomes more complicated by the availability of human-caused waste and attractants – therefore resulting in further conflict and bear euthanizations.

It was our last night in the alpine zone. We reached our destination, Moose Lake, in the early afternoon, and had the rest of the day to enjoy our last night at elevation. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw a sleek figure meander along the shore. The shape of the creature slowly came into focus. There was a Black Bear wandering only twenty feet away from our campsite, scrambling along the rock edge, looking blissfully serene as it glanced back and forth to the shore ahead and the crystal clear water. Barely looking our way, the bear prodded into the distance, its body ebbing and flowing with the gently lapping shoreline. It continued along the water’s edge before disappearing on the far side of the lake.

My experiences in the California backcountry have shown that mutual respect between our species is possible – and has the power to be a beautiful relationship. In the face of climate change, we must learn to co-exist and compromise with care and empathy in our ever-evolving landscape.

To learn more about the connection between humans and species like bears, watch the webinar we hosted in partnership with GBH last year. In The Goldilocks Strategy: Getting Our Relationship with Bears and Lions Just Right, hear straight from experts working with lions and bears and communities that live alongside them.

Adrianna Drindak is a rising senior at Dartmouth College studying Environmental Earth Sciences and Environmental Studies. Prior to interning at Bio4Climate, she worked as a field technician studying ovenbirds at Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest and as a laboratory technician in an ecology lab. Adrianna is currently an undergraduate researcher in the Quaternary Geology Lab at Dartmouth, with a specific focus on documenting climate history and past glaciations in the northeast region of the United States. This summer, Adrianna is looking forward to applying her science background to an outreach role, and is excited to brainstorm ways to make science more accessible. In her free time, Adrianna enjoys reading, baking gluten free treats, hiking, and backpacking.

Sources:

- https://bear.org/bear-facts/black-bear-range/

- https://westernwildlife.org/black-bear-ursus-americanus/biology-behavior-3/

- https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1365-2664.13021

- https://www.unr.edu/nevada-today/news/2025/bear-climate-research

- https://boulderbearcoalition.org/

- https://www.kcra.com/article/california-deadly-black-bear-attack-on-human-sierra-county/61009436

- https://blog.nwf.org/2025/01/awake-in-winter-how-climate-change-is-disrupting-black-bear-hibernation/

- https://www.adirondackexplorer.org/adirondacks-almanack/fed-bear-is-a-dead-bear/