Which creature is one of the largest snakes in the world, a popular exotic pet, and an unwanted addition to the Florida Everglades ecosystem?

One summer in high school, a close friend confessed that her parents had committed a crime when she was little. They released their two pet goldfish into a small pond behind her house to see what would happen. As far as experiments go, it was uneventful: the pair of fish grew to a respectable size, enough so that someone staring intently at the little pond could catch flashes of orange now and again. My friend’s goldfish fared well in her tiny pond, but could have also succeeded in a larger, more competitive environment. Goldfish thrive in most settings, so it is likely that they would outcompete native fish for food resources in the process of survival. However, the goldfish is not the only exotic pet with this potential. Governments around the world recognise this, which is why the release of pets into the wild is a legislated issue.

Many species can illustrate the need for these laws well, but one particularly dramatic story exists in the Florida Everglades: that of the Burmese python. What was once a popular pet has now become Florida’s nightmare, a situation so dire that massive swaths of Florida society have mobilized to hunt these former pets and their descendants en masse through the Everglades. While the Burmese Python has found a comfortable habitat in Florida, its tendency to eat everything in sight has made the state unable and unwilling to accommodate it.

Burmese Python Basics

The simplest way to understand what a Burmese python looks like? Ask a kindergartener to describe a snake. The Burmese python is a massive, formidable serpent. Although female Burmese pythons grow to larger sizes relative to their male counterparts, the average python commonly reaches lengths of 10-15 feet, but can grow over 20 feet and weigh in at 200 pounds. At this size, they can easily suffocate small mammals and other similar-sized prey.

The Burmese python is an r-selected species with reproductive traits ideal for turbulent situations. The Burmese python reaches reproductive age between four and five years old and can reproduce throughout its life. The average Burmese python lives to be 15-30 years old, depending on if it’s in the wild or captivity, and reproduces once per year. One clutch of eggs can be anywhere between 50 and 100 individuals. The average clutch has only a 38% survival rate, but this is all part of the snake’s plan of quantity over quality of maternal care. This reproduction strategy, combined with the python’s unfussy diet, allow it to adapt to new environments, and even outcompete native species for food and resources to the detriment of the ecosystem’s health: the definition of an invasive species.

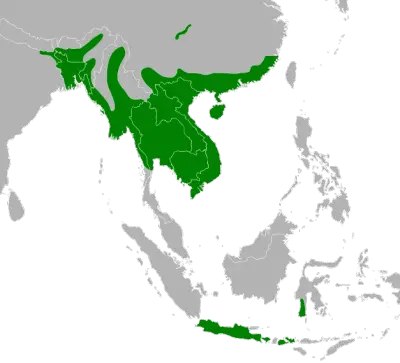

Courtesy Animalia.

Burmese pythons exist in a variety of settings with varying degrees of success. Firstly, they often exist in captivity as a lucrative part of the exotic pet trade.

The python is an apex predator in the wild, and the only notable threats adult members of the population face are from humans, namely, poaching and industrial development. These issues are most prevalent in certain areas in the Burmese Python’s native range in Southeast Asia. In some zones, populations have declined by 80% in a single decade. The Burmese python is therefore globally classified as a “threatened” species. Overall, the Burmese python has found the most success in the Florida Everglades, where it can hide in the vast, untouched, and diverse ecosystem.

The Florida Everglades, a Biodiverse Haven

The Florida Everglades is one of the largest wetlands in the world and an incredible source of tourism for the state. It is also the primary freshwater source for a third of Floridians, and provides water for most of the state’s agricultural ventures. None of these vital functions, however, are the reason that Everglades National Park was created. Instead, early local conservationists, such as the Florida Audubon Society and Marjory Stoneman Douglas, believed that the area’s unique and considerable biodiversity was worth preserving. These voices won despite fierce opposition from game hunters and other interested parties, and Everglades National Park was authorized by Congress in 1934 with the Everglades Act and formally established in 1947. It became the first US national park created to preserve biodiversity.

As biodiversity continues to decrease globally, the statistics comprising the Everglades become even more significant: the many endangered, endemic, and otherwise rare species comprising the Everglades should serve as a shining example of the importance of ecosystem preservation in the US. Instead, the Everglades today is only 50% of its original land size and faces an onslaught from many familiar sources. For one, agricultural activity in the greater Everglades Agricultural Area (EEA) has predictably led to fertilizers and pesticides being found in the Everglades system.

Moni3, public domanIncreased industrial and residential development in Florida has also had an impact. Many of these projects date back to the 1940’s, when large swaths of the Everglades were drained for industrial and agricultural purposes. These have resulted in a 70% reduction of water flow from Lake Okeechobee to the Everglades and beyond. The secondary effects of this decreased water capacity are serious. In addition to many rare species, the Everglades feature acres of peatland, consisting of soil incredibly dense with decomposed organic matter, leaving behind carbon and nitrogen. As these areas have received less water and experienced drought, allowing oxygen to move in and decompose the peat, releasing carbon, nitrogen, and other material into the atmosphere. Finally, the Burmese python has spent decades wreaking havoc on the Florida Everglades. In the face of these challenges, the Florida and federal governments have had limited success.

Other entities, however, have voiced concerns over the situation, as well as a desire to be involved in decision making, such as the local Seminole and Miccosukee tribes, who have called the Everglades home for generations. The Second Seminole War began in 1835 over the Seminole and Miccosukee peoples’ forced relocation west of the Mississippi from their reservation north of Lake Okeechobee in what is now central Florida. Many native forces used the Everglades as a refuge and meeting place during the conflict. By the third Seminole war, most of the nation had moved west, those who stayed dug deeper into the Everglades.

Today, the Seminole tribe is heading the ambitious Everglades Restoration Initiative, a $65 million dollar project that is mostly focused on improving the Everglades water system. The initiative aims to clean the water of pollutants, increase water storage capacity, and lobby for decreasing development projects in the greater Everglades area. Furthermore, the Miccosukee people have been successfully lobbying governments on behalf of the Everglades for decades, including fighting legal designations that would force the native population to vacate the Everglades. It is this continued ignorance from the government that has led organizations such as the National Academies to call for increased cooperation between the groups: after all, ancestral knowledge of the ecosystem predates western scientific knowledge. For one, the Miccosukee and Seminole peoples have a better understanding of how a restored Everglades should look. The governments of the United States and Florida have also had limited successes in addressing other issues plaguing the Everglades, such as an aforementioned invasive species.

A Long Way From Home

Rome wasn’t built in a day, and neither was the Florida Everglades branch of the Burmese python family. The first pythons in Florida arrived in the 1970s and early 80s as a popular exotic pet. However, breeders and owners alike allowed many snakes to escape into the wild. These individual cases mostly slipped by undetected. The real catalyst for today’s python crisis was Hurricane Andrew, which hit Florida in 1992 and led to many snakes escaping from a breeding facility.

These snakes rapidly found a home in the familiar, subtropical Florida Everglades, where their r-selected tendencies helped them thrive.

But what exactly is the problem with the Burmese python being in the Everglades? An invasive species thrives at the expense of the health of a larger ecosystem. Much like their fellow invasive species, such as the Asian Carp, the Burmese python is a predator with an appetite so large that their new ecosystem cannot provide enough food. It’s what’s known as a carrying capacity overshoot. In the Everglades, their unchecked predation devastated native mammal populations.

Although the snake primarily snacks on small mammals, no creatures are really safe. A widely cited 2012 study found that between 1997 and the publication, raccoon numbers in the Everglades (once an incredibly common sight) had declined by 99.3 percent. Fellow common mammals in this study barely fared better, with all population crashes being over 85%. Most damningly, sightings of these animals were often in areas where pythons were not present or had only been recently introduced. Other species, like marsh rabbits and foxes, “effectively disappeared over that time.” Today, estimates of their population in the Everglades range from 100,000 to 300,000 individuals.

Photo: Tigerpython

A Serpentine Smear Campaign

It wasn’t until 2000 that the Burmese python was officially recognized as an established species in the Everglades. In 2006, the Florida government took a soft approach to eliminating pet python releases with the new Exotic Pet Amnesty program.Through this program, pet owners could connect with parties interested in taking their unwanted pets free of charge. Two years later, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission (FWC) decreed the python as a “reptile of concern.” This distinction meant that the Burmese python could only be kept as a pet after a potential owner jumped through bureaucratic hoops.. The effectiveness of these solutions to the python’s presence in the Everglades was limited, as working to prevent snake releases does not address the already-established local population.

It is important to note that during this early period, the most effective and robust solutions to the python invasions came from local and national non-profits. In 2008, the Nature Conservancy launched its Python Patrol program for the Florida Keys, an initiative that trained volunteers in the best methods of python seeking and euthanizing. The Nature Conservancy partnered with Everglades National Park in 2010 and the FWC took over the program following its success.

A parallel yet arguably more impactful program was that of the local Conservancy of Southwest Florida. Unlike the Nature Conservancy, their efforts comprise a larger number of innovative strategies. Firstly, they considerably publicized the efforts of their eradication and removal volunteer crews: several videos went “viral” on a global scale, which helped raise awareness toward the issue. They also pioneered a high-tech elimination strategy that involved catching and airtaging male pythons of breeding age in order to track their movements to python nests.

In 2012, the Obama-era US Fish and Wildlife Administration decided to weigh in on the python problem. The Burmese python, along with several other exotic snakes, was designated as a Prohibited Species under the Lacey Act. This act is one of the oldest pieces of conservation legislation in the United States. Dating back to 1900, it bans the interstate sale and purchase, importation, exportation, etc, of a list of specific plant and animal species without a permit. Later amendments were more comprehensive and dealt with wildlife shipment labelings, timber supply chains, and other mechanisms affecting the transport of foreign species. The ability to own one of these animals, such as the Burmese python, is a matter left for individual states to decide.

Despite a myriad of eradication efforts, experts and officials share the opinion that eradicating the Burmese python from Florida is nearly impossible.

Lessons Learned

Unfortunately, it is far too easy to blame the processes of government in this story, as decisive action was quite delayed. Legal theorists over the years have also pointed out that the Lacey Act has a loophole, whereby government agencies cannot take action against an already established invasive population. In the future, should it be the responsibility of the government to take preemptive preventative measures to protect biodiversity? Despite their smaller role in this story, I would venture a yes: as development projects threaten the stability of the Everglades as a water purifier and essential ecosystem, the law is needed to stop these endeavors in spite of the market forces demanding their creation.

The state of Florida remains an absolutely essential player in hopes of preserving the Everglades. However, the old and continuing story of Everglades conservation is absolute proof of the power of non-government entities to motivate legal and public policy actions. The state would therefore be wise to consult not only pioneering non-profit conservationists, but the longtime local experts that call the national park home.

Alexa Hankins is a student at Boston University, where she is pursuing a degree in International Relations with a concentration in environment and development policy. She discovered Bio4Climate through her research to develop a Miyawaki forest bike tour in greater Boston. Alexa is passionate about accessible climate education, environmental justice, and climate resilience initiatives. In her free time, she likes to read, develop her skills with houseplants, and explore the Boston area!