What creature has a lifespan of over 250 years and catches prey by suction?

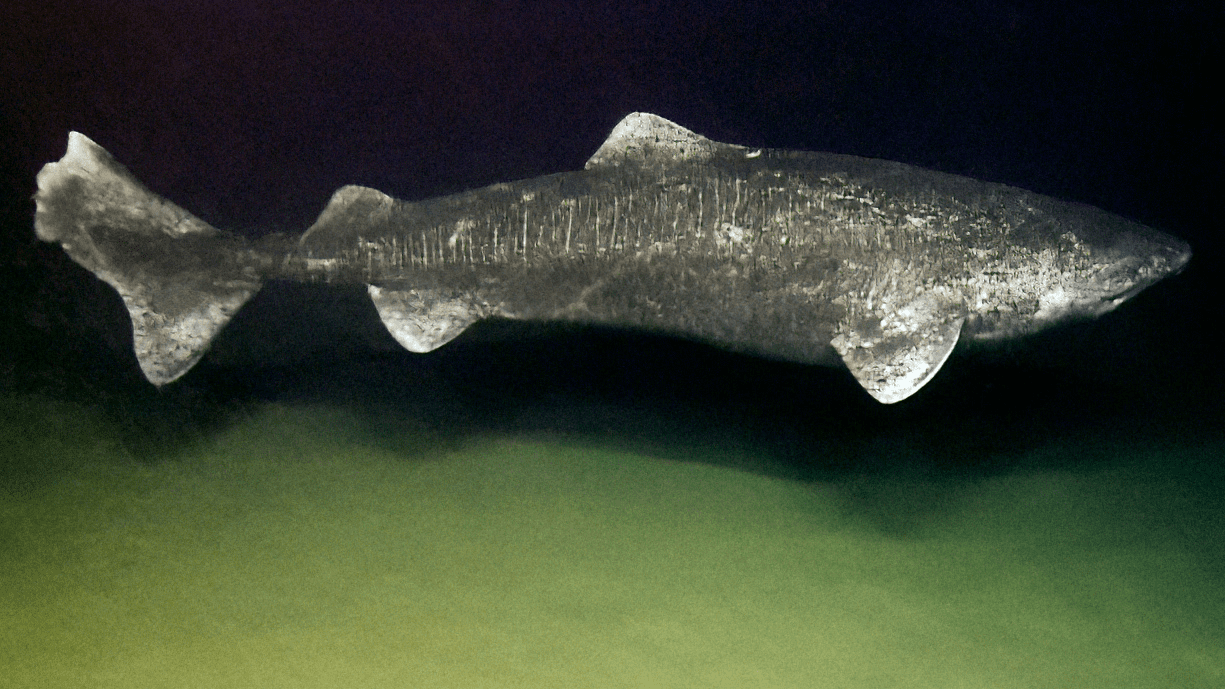

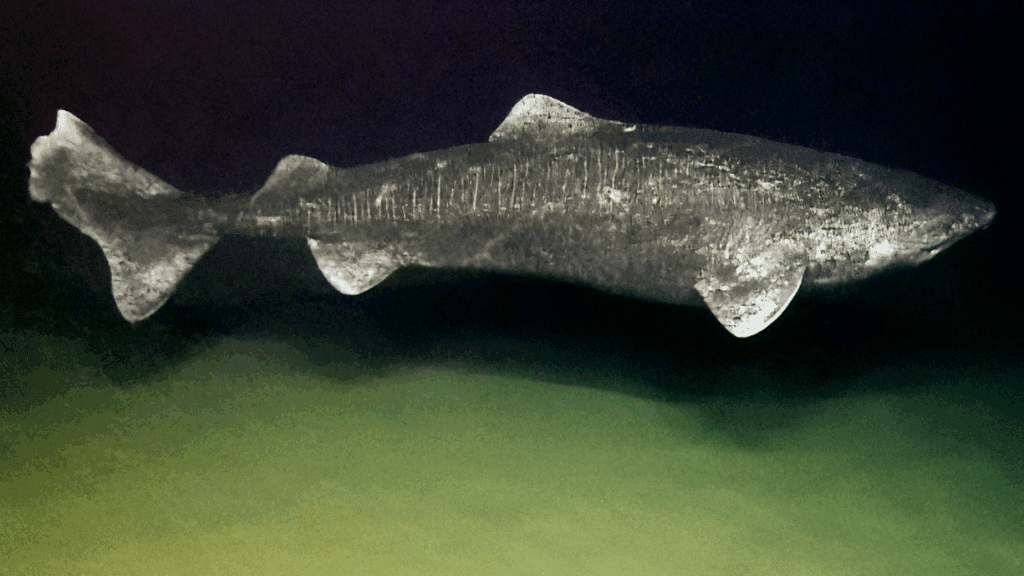

The Greenland Shark (Somniosus microcephalus) is one of the oldest and largest sharks in the world. It is the biggest of its superorder, Squalomorphii (one of the two groups of sharks). They can get up to 21 feet and 2,255 pounds, and have an average lifespan of 272 years. The oldest recorded Greenland Shark was almost 400 years old; that shark was alive during the Scientific Revolution! When I first came across these sharks and their longevity, I was fascinated. There are so many interesting things about this creature, so let’s take a look!

Amazing Adaptations

Unlike most other sharks, Greenland Sharks like cold, deep water, and are usually found near the Arctic or Atlantic Oceans. Greenland Sharks have special adaptations that help them thrive, and allow them to survive near-freezing water temperatures and high water pressure.

For one, they’re big animals, and larger animals tend to have slower metabolisms and therefore age slower. Their slow metabolisms also mean they move almost lethargically. This gives them part of their scientific name, Somniosus microcephalus; “Somniosus” comes from “somnum”, the latin word for sleep! That’s why they’re also called sleeper sharks.

If they’re so slow, how do they catch prey so fast? Greenland Sharks are known to eat seals, fish, and other fast aquatic animals, but they can only reach a maximum of around 1.6 miles per hour (one of the slowest animals of their size!). They primarily catch food by ambushing prey while they’re asleep, and by targeting injured animals. Since there’s little to no light at the depths these sharks are found at, and they’re usually dark colors, they can sneak up and surprise other creatures. They also have a special method of actually “grabbing” their targets. They open their mouths fast, creating a suction force that draws water (and the animal) into their large mouths, allowing them to swallow some prey whole.

Another example of Greenland Sharks’ adaptations to their environment is the fact that they have specific chemical compounds in their bodies that help them in different ways. The two common ones are urea and TMAO (trimethylamine N-oxide). Since these sharks are constantly surrounded by saltwater at high pressure, lots of urea in their body helps the shark’s cells keep their shape. This is why they’re classified as osmoconformers: they have high concentrations of urea in their body to match high concentrations of salt in the outside water, keeping a balance. Also, both urea and TMAO help the shark be less dense, allowing it to float better.

Urea does also have some negative side effects: too much of it can destabilize enzymes within the shark, hurting them and keeping proteins in their body from functioning correctly. TMAO counteracts this, stabilizing proteins even when there’s a lot of urea. This process allows Greenland Sharks to survive without trouble in the Arctic Ocean.

While these chemicals are helpful to sharks, they’re absolutely not for humans. TMAO in particular is extremely toxic to mammals, and can lead to extreme sickness or death. People do eat them, though! These sharks are a delicacy in some places: Hákarl, cubes of fermented Greenland Shark meat, is the national dish of Iceland. Because of the TMAO and urea, the meat has to be dried for weeks or months, and fermented in a certain way so it becomes safe for human consumption.

Deep water usually doesn’t get much light, so these sharks adapted by also evolving other ways to “see”. They have an incredible sense of smell and rely heavily on it for navigation. They also have the ability to sense electric fields through special gel-filled pores all over their snout and face! This sixth sense lets them detect small movements and even heartbeats, allowing them to navigate both on a small scale (their immediate surroundings) and a large scale (Earth’s magnetic field).

In fact, their other senses are so well-developed that they don’t need sight at all. Many Greenland Sharks’ eyes become infected by a copepod called Ommatokoita elongata. This parasitic crustacean gets permanently attached to the corneas of the shark, injuring their eyes and sometimes rendering them completely blind (though the sharks don’t notice or care!). These creatures can sometimes have bioluminescence, making the shark look as if it has glowing eyes. It’s been theorized that, in the darkness of the water, this spot of light may help the shark attract prey.

Important interactions

Greenland Sharks have been around for a long time, and lots of different people have interacted with them in various ways. Because of their niche habitat range, accidental encounters are rare, and there haven’t been any recorded human attacks. These sharks aren’t aggressive (like most sharks, even though they get a bad reputation). Since they’ve been around for over a million years, different cultures have had different peaceful interactions with Greenland Sharks.

Sightings of these sharks may be behind the legends of the Loch Ness monster (although other creatures might contribute, too). There are also Inuit legends involving these sharks. Since they have such a high urea content, they smell like ammonia, or urine. One legend involves the sea goddess Sedna throwing a urine-soaked rag into the ocean, where it transformed into the first shark, a Greenland Shark. The nordic dish hákarl originally got so famous because when the meat isn’t fully fermented, it’s mostly non-toxic but has inebriating effects, which was thought to help people connect to and communicate with Sedna.

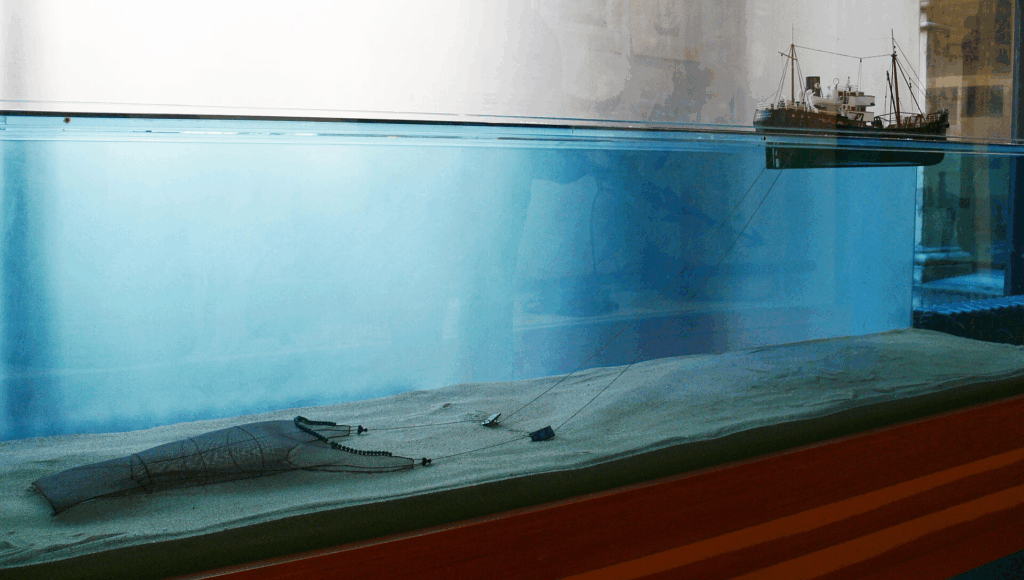

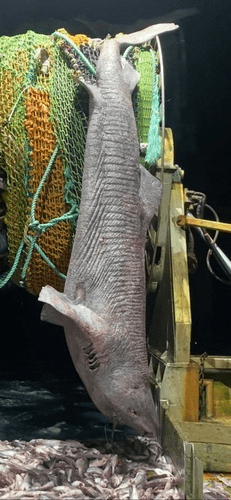

These sharks have had plenty of negative interactions with people, too. They used to be purposely hunted for the production of certain oils. This doesn’t happen as much anymore, but they are still a frequent bycatch species. This means that they’re often accidentally captured or killed in the process of trying to catch some other animal. Modern fishing methods make bycatch more and more common, and this results in overhunting of many fish species around the world. Trawls are one of the most problematic examples of this.

A trawl net is a large, basket-like net that’s weighted to drag along the sea floor. Boats pull the nets along the ground at high speeds, and any animal in the way gets scooped up and trapped. This is terrible for sea life; imagine if you were a little sea creature at the bottom of the ocean, and out of nowhere an almost-invisible net grabs and traps you along with everyone else nearby. Entire populations of animals get captured in these nets, and most of them end up getting thrown away! Bottom feeders, or species that spend their time on the ocean floor (like Greenland Sharks), are typically deemed undesirable for selling. The targeted fish species only end up being a tiny fraction of the total catch, and the rest often gets discarded.

Not only is this fishing method inefficient and wasteful, the nets damage homes of ocean animals by breaking or smashing everything in their path. Annually, around 3,500 Greenland Sharks are caught and killed as bycatch. Fishing methods like these have resulted in a decline in Greenland Shark populations, as well as many other aquatic animals.

Other factors relate to the well-being of Greenland Sharks, and global warming is a big one. Since these sharks love cold water, they usually stay around the Arctic circle. Global warming is making this water a little warmer than it used to be, and a lot of the sea ice is melting.

Greenland Sharks have extremely long lifespans, but they also have low fertility rates and long gestation periods (how long it takes a baby to develop). Greenland Sharks have gestation periods of around 8 to 18 years. This means that it takes them a long time to replace population members. If too many die at once, baby sharks might not be born fast enough to save the population.

All of these factors influence the rarity and vulnerability of these sharks.

The IUCN Red List is a list that keeps track of vulnerable or endangered species. In 2020, Greenland Sharks got reclassified from near threatened to vulnerable. Unfortunately, since they have such a slow recovery time, their status will probably continue to get worse. This is bad news for a very strong reason: Greenland Sharks are incredibly important to their ecosystems.

As apex predators, they eat pretty much everything, including fishes and seals. They’re able to do this by ambushing prey, as described above. This helps them keep those populations in check by controlling how many of their prey species there are. If Greenland Sharks went extinct today, those other species would multiply. They would quickly take over ecosystems, destabilizing them, interrupting food chains, and overall harming everyone. Greenland Sharks prevent this by acting as a neutralizing force on population sizes of other fish. These sharks are important for maintaining balance in their environments.

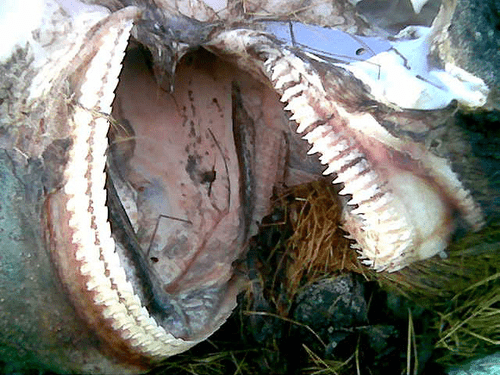

Greenland Sharks are scavengers; they eat carrion and other dead matter. They can eat large carcasses of animals that fall to the bottom of the oceans (like whales; have you ever heard of a whalefall?). Greenland Sharks actually have very unique, specialized teeth to let them do this; their upper teeth are small, thin, and pointy. Their lower teeth are chunkier with complex shapes that point away from the top teeth. This lets them tear off large chunks of meat when they roll their jaw. Teeth like this are another incredible example of Greenland Sharks’ specialized evolution! Eating already-dead animals lets them get energy and nutrients from other sources, “recycling” it and putting it back into the ecosystem.

Overall, Greenland Sharks are very important to their environments, and their removal would have disastrous effects on surrounding sea life.

To me, these weird, fascinating sharks are incredible. They have strange and unique adaptations that help them survive their extreme environments, and they’re important to those environments because of their interactions with other species. Because of the specificity of their Arctic circle deepwater habitat, they’re relatively poorly studied. There isn’t that much recorded information on them; we still have a lot of unanswered questions. After learning more about them, I’m personally interested in how they’re able to survive for centuries (some genetic research implies it’s related to transposons, or “jumping genes” that can move around the chromosome!).

And while I tried, there’s also a lot about these sharks I didn’t mention. You can read more about their genetics here, about their longevity here, and about the harms of overfishing and trawling here.

Anya Reddy is a high school student at Blue Valley North. She loves biology and biochemistry, as well as entomology, ecology, and environmental science in general. Some of Anya’s non-science passions include archery and all kinds of 2D and 3D art. She enjoys learning about all kinds of organisms and how they connect and interact with others in their environment; she hopes to use writing to help share fascinating details about them, helping others like the weird and interesting organisms she loves.

Dig Deeper

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/fish/facts/greenland-shark

- https://www.sharksider.com/greenland-shark/

- https://www.livescience.com/greenland-shark

- https://nbscience.com/greenland-shark-somniosus-microcephalus-greenland-shark/

- https://saveourseas.com/worldofsharks/what-are-the-biggest-sharks

- https://wordpress.evergreen.edu/somniosusmicrocephalus/deep-sea-adaptations/

- https://www.trackingsharks.com/monster-inuit/

- https://usa.oceana.org/reports/impacts-bottom-trawling-fisheries-tourism-and-marine-environment/

- https://mustreadalaska.com/trawl-bycatch-understanding-the-serious-harm-to-alaska-and-the-possible-solutions

- https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.09.09.611499v1

https://thebiologist.rsb.org.uk/biologist-features/very-cold-and-very-old

https://sharkresearch.earth.miami.edu/commercial-shrimp-trawling-the-profit-does-not-out-weigh-the-damaging-effects-on-rest-of-the-ecosystem/