What athletic creature can reach speeds of 45mph and cool itself down with large ears – all in a 2.5 kg frame?

The Iberian hare (Lepus granatensis)!

Five times the size of New York’s Central Park, Casa de Campo (literally, “country house”) outside Madrid is filled with rustic stone pine trees – emblematic of the Mediterranean and easily identified by their bare trunks and full, blooming crown of pine needles. It’s sometimes called the “umbrella pine” for good reason. Above, within, around, and beneath these trees, nearly 200 species of vertebrates live.

Out for a run through the park, my feet pounded the dry dirt along a gradual decline for the last mile. Here, the earthen trail dipped down steeply and cut through dense brush. As I dropped in, I almost landed squarely on top of what appeared to be a large rabbit. To my surprise, it didn’t dart away; I think I was more startled than it was. You see, I’d set out on that run in part to find inspiration, follow my curiosity, and think of a creature I wanted to learn more about. I’m not such a strong believer in fate, but this rabbit (or so I thought at the time) had certainly made its case.

I lingered and watched it mill around the brush. The more I watched, the more I wondered about its story.

A Keystone Species On The Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian hare (Lepus granatensis) is endemic, or native, to the entire peninsula that contains Spain, Portugal, and the enclave nation of Andorra. Throughout that region they can be found in diverse habitats including dry Mediterranean scrublands, woodlands, and agricultural fields. It thrives in regions with ample vegetation that offer cover and food, adapting well to the peninsula’s varied landscapes, which range from dry, hot areas to slightly cooler, temperate zones. In some respects, Casa de Campo itself is a microcosm of these environments.

Lepus granatensis is a keystone species, meaning it occupies an essential link in the ecosystem’s food chain and plays a particularly outsized role in balancing its environment. It survives on a diet of grasses, leaves, and shoots, playing a crucial role in seed dispersal and vegetation control – and is a source of prey for a range of birds and mammals. The hare’s diet and grazing habits help control plant overgrowth and support a diverse plant community, evidenced in Casa de Campo by the more than 600,000 plant specimens found in the park alone.

The open ground this hare navigates every day is patrolled by animals who want to eat her– lynx, coyote, and red foxes from the land and eagles, owls, hawks, and red kites from the air. To get from point A to point B she must be fast, and she is. Powerful hind legs propel Lepus granatensis to top sprinting speeds of 45-50 miles-per-hour, making her one of the fastest land animals on the peninsula. It’s a pace that puts my nine-minute mile to shame, and is an essential adaptation to survive here, far from the relative safety of dense forest or lush meadow.

Image by author, who was apparently far too busy taking pictures instead of running while on his run.

Nature’s Air Conditioning

When I first started coming to Madrid, adapting to the sparing or non-existent use of air conditioning in the summer was an adventure, to say the least. I can do without the Chipotle and readily available iced coffee, but having been raised on A/C since I was born, it took some getting used to. Unlike me in this regard, the hare I ran into that day is well suited to her environment. It is one of large, open landscapes dotted with thick low lying brush, olive trees, holm oaks, and pines. Rainfall is infrequent, and summers are scorched by the strong Spanish sun.

Her ears are larger and thinner than those of a rabbit. They often stand upright. When backlit, one can easily make out a network of veins and arteries, traversing the ear like rivers and streams through a watershed.

Image by author.

Therein lies her secret. Hares don’t perspire like you and me– nor do they pant like a canine. Instead, they depend on their large, thin-skinned ears to act as thermostat and air conditioner. No, they don’t flap them like a paper fan. Instead, they help her cool down by getting hotter.

When the hare needs to release excess heat, she can expand that network of blood vessels in her ears, allowing her to redirect hot blood away from her body and through the thin skin of her ears. Because her ears have a large surface area putting those veins in closer contact to the ambient air, this increased blood flow facilitates the dissipation of heat into the ever so slightly cooler surrounding air, helping her regulate her body temperature effectively.

We see this strategy of counter-current thermoregulation in nature again and again, in the ears of elephants and deer, and a variation in the snow and ice-bound paws of the arctic fox.

heat disparity between a rabbit’s ears, and the rest of its body.

Confronting a Microscopic Threat

Before I continued my run, I fired off a few observations to a zoologist friend of mine for help with the species identification. Among them was what we suspected to be a bad case of conjunctivitis in both eyes; significant levels of swelling and discharge were present.

While neither of us can offer a certain diagnosis for this particular hare, further research has indicated that something more serious is afoot.

In 1952, France was well into its post-war reconstruction, buoyed along by a growing economy and population. As the country was just beginning a new chapter in its story, so too was recently retired physician Dr. Paul-Félix Armand-Delille. In his new-found free time, Armand-Delille took up great interest in the pristine care and management of the grounds of his estate, Château Maillebois, in the department of Eure-et-Loir, a little more than 100km west of Paris.

Troubled by the presence of wild European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) on his property, Armand-Delille read about the success Australian farmers had found using strains of the myxoma virus to control invasive rabbit species on that continent (they’d been imported by an Englishman decades earlier). Using his old medical connections, Armand-Delille secured some myxoma virus for himself and intentionally infected and released two of the rabbits on his property, confident that they would not be able to leave it.

Image credit: Marcengel (CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons)

In just one year, nearly half of all wild rabbits in France would be dead, consumed by myxomatosis, the disease caused by the myxoma virus. In the decades since, the disease has ravaged Oryctolagus cuniculus populations across Europe, shrinking their numbers to just a fraction of what they were at mid-century. The sudden, near overnight disappearance of the European rabbit also crippled populations of its specialist predator, the Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus). With the lynx unable to replace the rabbit in its diet, the species was pushed to the brink of extinction. Recent conservation efforts have helped recover and stabilize populations, but Lynx pardinus remains a “vulnerable” species.

Fortunately, over just the last few decades some populations of the European rabbit have resurged, having developed strong resistance to the virus.

But viruses are always trying, though usually failing, to jump from one host species to another. As species migrate and habitats converge, a virus gets more and more chances to make the leap.

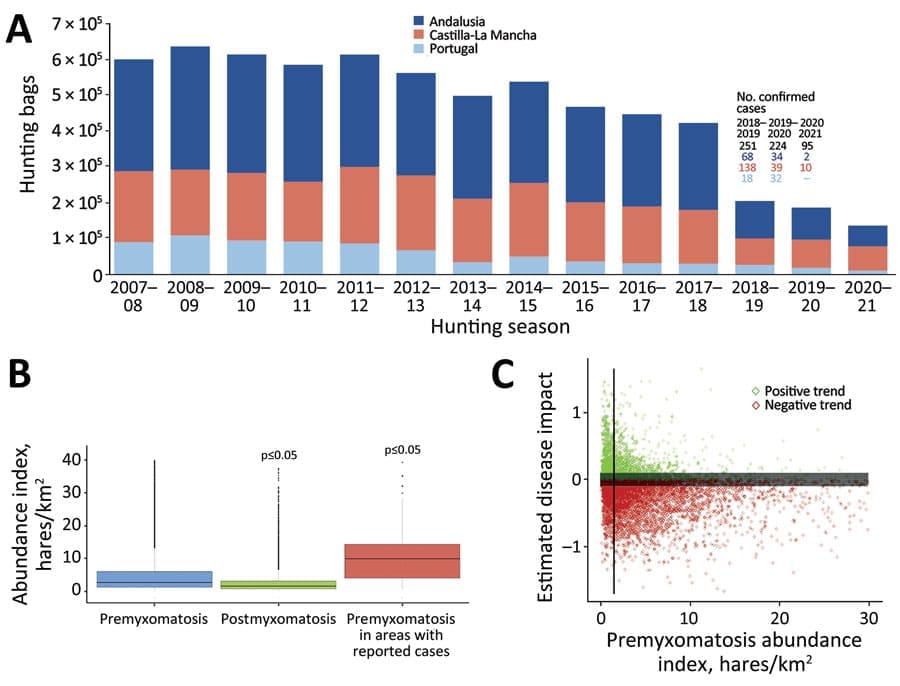

As early as 2018, myxoma succeeded in making the leap from Oryctolagus cuniculus to Lepus granatensis. The virus that causes myxomatosis has wreaked havoc on Iberian hare populations on the peninsula; a species that did not have the advantage of decades and decades of exposure to build up resistance. Myxomatosis can cause fever, lesions, lethargy, and, it turns out, severe swelling and discharge around the eyes. Sometimes these symptoms can subside. But for the Iberian hare the virus is remarkably lethal, with a mean mortality rate of about 70%. Data indicates that since 2018, the virus has decimated Iberian hare populations. This break in the chain has serious implications for both the vegetation the hare keeps in check and the predators that depend on the hare as prey – implications that we are only beginning to understand.

As a warming world continues to heat Iberia, the delicately balanced ecosystem Lepus granatensis inhabits is increasingly jeopardized. More intense storms flood the parched terrain while stifling heat and wildfires threaten vegetation. Lepus granatensis is likely to migrate north in search of more tolerable environments that can sustain the plant life it depends on for both food and cover. The further north the hare goes, the more its new habitat will overlap with the European rabbit and other species. The future of large populations of Lepus granatensis in the face of this disease and increasing climate fallout is uncertain. Since returning to Casa de Campo, I’ve noticed the swelling and discharge in other leporids as well.

Image credit: JoseVi More Díaz (CC-BY-NC-ND)

Complexity

This isn’t the story I set out to tell. When I stumbled on the hare, I expected to write an essay about reconnecting with nature as I embarked on my own new journey as part of the Bio4Climate team.

Transitioning from a place of hope and curiosity, to understanding the more dire situation faced by both the hare I crossed paths with and the species as a whole was deflating. Yet, that’s all part of nature’s complexity; we don’t always get the happy endings we want. To some extent, these aren’t our stories to write. But even that conclusion is built around a false premise, because none of these stories are over.

The recent outbreak has prompted renewed research interest into threats facing hare populations. And even if we distill the bigger story down to this specific hare, I don’t know what will become of her. No, the odds aren’t great. But in the time that I watched her she simply carried on, foraging away in the brush. It’s a small thing to observe, but I think there’s hope in that— in identifying the struggle and the resilience of living things, and channeling that understanding to shape a better world.

It’s hard not to think about the web of plants, animals, ecosystems, and microscopic organisms that have been set on a collision course with each other as they seek to rebalance themselves. And in the middle of it all is us.

After watching the hare for a few minutes, I continued my run. The trail led out of the brush and opened up into a large, flat field, sparingly dotted with those umbrella pines. At that moment, a bird I later identified in iNaturalist as a red kite (Milvus milvus) dropped out of one of the trees, skimmed the earth, and climbed into the sky.

Brendan began his career teaching conservation education programs at the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium. He is interested in how the intersection of informal education, mass communications and marketing can be retooled to drive relatable, accessible climate action. While he loves all ecosystems equally, he is admittedly partial to those in the alpine.

Sources and Further Reading:

Articles

- Myxoma’s Viral Leap into Iberian Hares Sheds Light on How Viruses Swap Genetic Material by Gabrielle Hirneise

- Return of the Missing Lynx, Rewilding Europe

- Darwin’s Rabbit is Revealing How the Animals Became Immune to Myxomatosis by Josh Davis

- Lepus granatensis: Granada hare by Derek Weaver

- Casa de Campo – Official Madrid Tourism

Scientific Papers

- Unraveling the Genomic Landscape of Myxomatosis Susceptibility in Iberian Hares (João P. Marques, et al., 2024)

- First Cases of Myxomatosis in Iberian Hares (Lepus granatensis) in Portugal (Carina Luísa Carvalho, et al., 2020)

- Effect of Myxoma Virus Species Jump on Iberian Hare Populations (Beatriz Cardoso, et al., 2024)

- Heavy Flooding Effects On Home Range and Habitat Selection of Free-ranging Iberian Hares (Lepus granatensis) in Doñana National Park (SW Spain) (Francisco Carro, et al., 2011)

- The Dynamics of Lepus granatensis and Oryctolagus cuniculus in a Mediterranean Agrarian Area: Are Hares Segregating from Rabbit Habitats after Disease Impact? (José Prenda, et al., 2022)

- The Health and Future of the Six Hare Species in Europe: A Closer Look at the Iberian Hare (Margarida D. Duarte, et al., 2020)

- Homeostatic Processes for Thermoregulation (Jonathan A. Akin, et al., 2011)

- Myxoma Virus and the Leporipoxviruses: An Evolutionary Paradigm (Peter J. Kerr, et al., 2015)