I prowl the woods, both fierce and lean,

With golden eyes and coat unseen.

Once a ghost upon the land,

Now brought back by careful hand.

Who am I, wild and free,

Yet bound by fate and history?

Many moons ago, for two years during college and one year after, I worked at the Columbus Zoo & Aquarium in central Ohio (for those keeping score at home, that’s Jack Hanna’s zoo. Yes I met him.)

I spent thousands of hours over hundreds of days at that zoo. I got to know every path, every Dippin’ Dots stand, and every habitat under the zoo’s care.

The Columbus Zoo & Aquarium has an incredible collection of creatures (they’re one of the only institutions outside of Florida with manatees). While I was enamored with all of them, my favorite were the Mexican Wolves, a critically imperiled species.

In a place full of more diversity and creatures than I could ever count, the zoo’s Mexican wolves were different. As part of the (American) Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ Species Survival Plan, a nationwide conservation effort. There were excellent educators of the impact one creature can have on an ecosystem, and what can happen when we don’t take care of them.

Credit: JCaputo via Flickr. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

A Predator on the Brink

The Mexican wolf (Canis lupus baileyi) is both the rarest and most genetically distinct subspecies of the more well known gray wolf. It is notably smaller than its northern relatives, with adults weighing standing about two feet tall at the top of the shoulder. Despite this (relatively) diminutive stature, the Mexican wolf is an apex predator in its environment, finely tuned by evolution for survival in the rugged, often unforgiving landscapes of the southwestern United States and northern Mexico.

Consider those landscapes for a moment. What does it take for a species already up against the ropes to survive there? What would it take for you to survive there?

You’d have to have exceptional endurance to hunt in vast, open environments. Long, slender legs and a streamlined body would allow you to cover these great distances while tracking prey, often over the course of 30 miles in a single day. You’d require an acute sense of smell and keen eyesight to pick up on the movements of smaller creatures from far away, even in the dim light of dawn or dusk when your prey is most active.

You’d be an expert of efficient thermoregulation, that is, keeping cool in the heat and warm in the cold. And you’d have to be, an expert, when your world ranges from scorching desert heat to bitter mountain cold, these wolves have developed a double-layered coat that provides insulation in winter while shedding excess warmth in summer. The coat’s coloration, a mixture of gray, rust, and buff, serves as excellent camouflage against the rocky and forested landscapes they inhabit.

A Wolf’s Role

It’s old news to you, I know, but it bears repeating. For ecosystems to function, predators must play their part. Like other wolves, the Mexican wolf is a keystone species, regulating prey populations and influencing plant communities. Without them, the system unravels.

The Mexican wolf primarily hunts elk, white-tailed deer, mule deer, and occasionally livestock, but they will also take smaller mammals like rabbits and rodents when such larger prey is scarce. When they hunt, they do so together, as cooperative pack hunters. Their strong social structure is as essential a tool as their razor sharp incisors in felling prey much larger than themselves. Beyond the hunt, these [ack dynamics are critical to their survival—each member has a role, from rearing the pups learning the ropes to experienced hunters leading coordinated chases.

Both on the hunt and at home, communication is central to the wolves’ social structure. Howling serves as both a bonding ritual and a way to locate packmates over vast distances. Body language, like tail positioning and ear movement, helps maintain hierarchy within the group. You may even recognize a few of these traits in your own dog, barking or howling to communicate, using their tail and ears to express emotion, or learning through playful wrestling as a puppy.

Packs are tight-knit, usually number four to six members, though some may grow larger depending on prey availability. They establish territories spanning up to 200 square miles, marking them with scent and vocalizing to warn off intruding wolves and other creatures.

Image by Bob Haarmans, CC BY 2.0

In the absence of wolves, prey populations, especially elk and deer, explode, stripping vegetation and weakening forests. Overgrazed lands mean fewer young trees, degraded soil, less cover for smaller animals and heightened wildfire risk. This domino effect, known more scientifically as trophic cascade, ripples through the entire ecosystem. Beavers lose the young saplings they rely on for food and dams. Birds struggle to find nesting spots. Streams warm without tree cover, altering aquatic life.

But when wolves return, balance begins to restore itself. Just ask Yellowstone National Park. Wolves keep elk and deer moving, preventing over-grazing in sensitive areas. Carcasses left behind provide food for scavengers, including ravens, eagles, foxes, and even bears. Their presence reshapes the landscape, not just through their actions but through the fear they instill in prey. They don’t just hunt; they change the way the river of life flows.

A Fragile Comeback

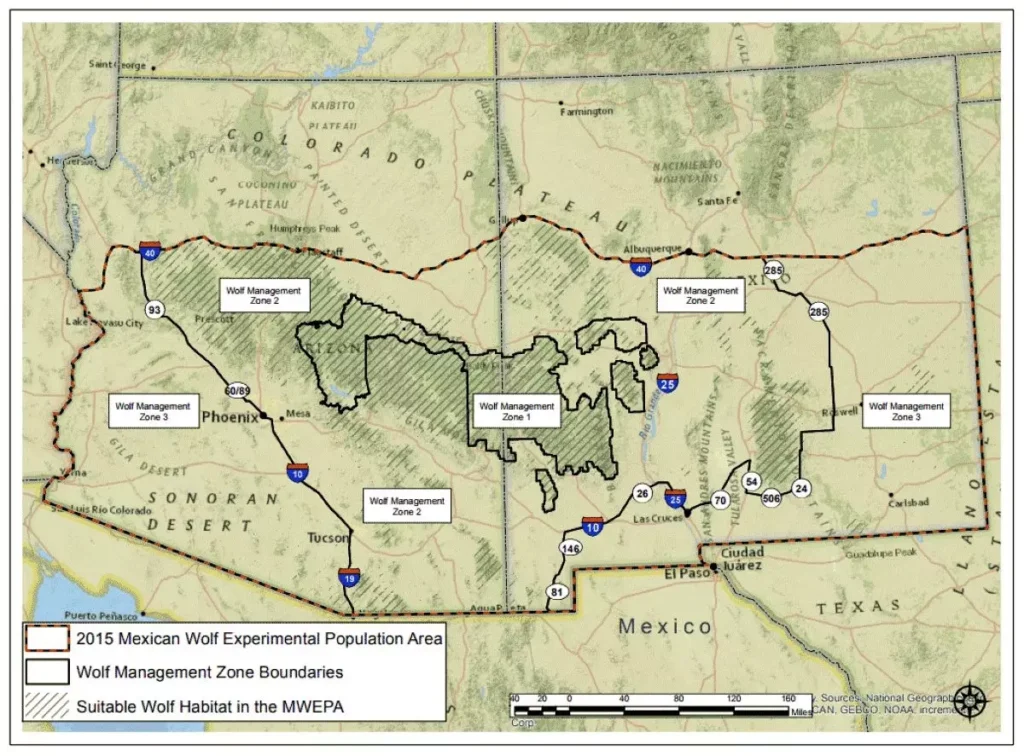

Conservation and reintroduction of Mexican wolves has been an uphill, if slightly progressive, endeavor since the first captive-bred wolves were reintroduced into Arizona and New Mexico in 1998.

Ranchers in the area saw them as a renewed threat to livestock, and illegal killings were common practice. Some reintroduced wolves were shot before they had a chance to establish packs. Others were relocated after venturing too close to human settlements and industry.

Populations have grown slowly. From a low of just seven wolves in 1980, there are now about 250-300 Mexican wolves in the wild today. This precarious population is still critically small, vulnerable to disease, low genetic variation, and continued conflict with humans.

Climate change has also complicated things.

Rising temperatures are altering the Mexican wolf’s habitat. More frequent and severe droughts in the American Southwest threaten prey availability, pushing elk and deer into different ranges. Increased wildfires, driven by hotter, drier, and more flammable conditions, destroy the forests that wolves depend on for cover and prey.

Last Word

I know zoos can be complicated, controversial places at times. I’m not really here to weigh in on that. But I think like many things in life, there is great value in the best parts of them. As we all continue to advocate for a less-extractive relationship with the rivers of life beyond our front door, I think the ability to educate, connect, and inspire others to care about the world around them is critically important. I saw the Columbus Zoo do that well time and time again, and I think every time we share a featured creature, post a picture of our gardens, or take someone along for a Miyawaki planting, we do the same.

Brendan Kelly began his career teaching conservation education programs at the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium. He is interested in how the intersection of informal education, mass communications and marketing can be retooled to drive relatable, accessible climate action. While he loves all ecosystems equally, he is admittedly partial to those in the alpine.