Which creature is the largest Asian antelope, considered sacred to some and pest to others?

The Nilgai!

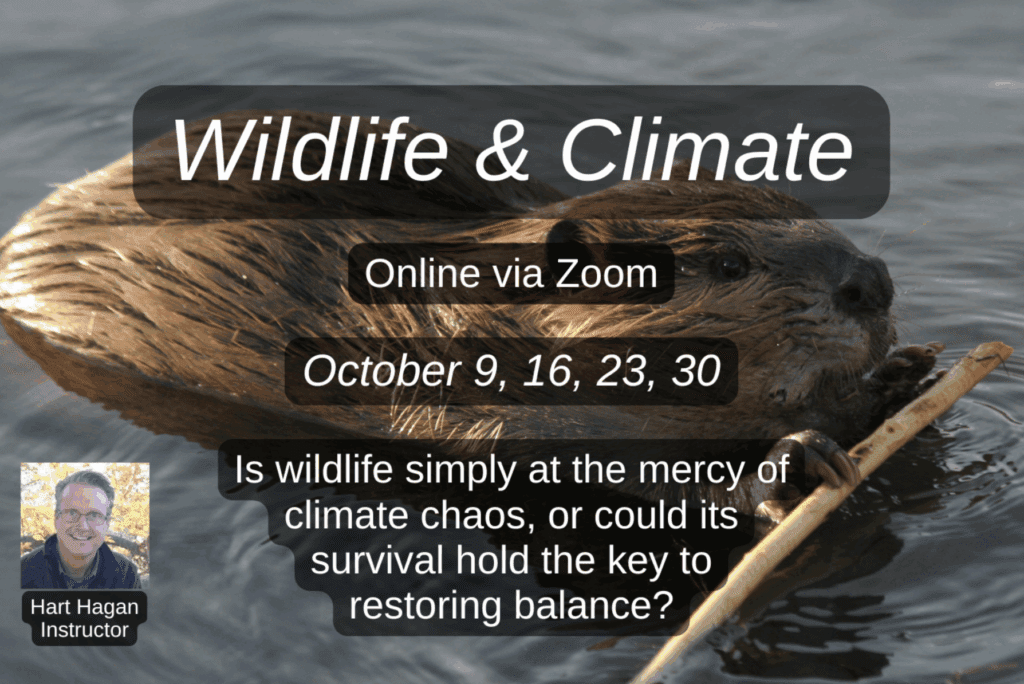

This fascinating four-legged friend could be described by a whole host of leading questions, depending on which notable features we want to emphasize. Elizabeth Cary Mungall’s Exotic Animal Field Guide introduced the nilgai with the question “What animal looks like the combination of a horse and a cow with the beard of a turkey and short devil’s horns?”

Personally, I find the nilgai much cuter than that combination might suggest, but it may all be in the eye of the beholder. The name ‘nilgai’ translates to ‘blue cow’, but the nilgai is really most closely related to other antelopes within the bovine family Bovidae. Mature males do indeed have a blue tint to their coat, while calves and mature females remain tawny brown in color.

As their physiology suggests, nilgai are browsers that roam in small herds, with a strong running and climbing ability. I encountered them in the biodiversity parks of New Delhi and Gurgaon, where efforts to rewild the landscape to its original dry deciduous forest make for ideal stomping grounds for the nilgai.

Prolific Browsers

Indigenous to the Indian subcontinent, the nilgai is at home in savanna and thin woodland, and tends to avoid dense forest. Instead, they roam through open woods, where they have room to browse, feeding on grasses and trees alike. They’re considered mixed feeders for that reason, and will adjust their diet according to the landscape. Nilgai are adept eaters, standing on their hind legs to reach trees’ fruits and flowers and relying on their impressive stature (which ranges from 3 to 5 feet, or 1 to 1.5 m, at the shoulder) to get what they need.

(By Akkida, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=34508948)

Like other large herbivores, nilgai play an important role in nutrient cycling and maintaining the ecosystems they’re a part of. In this case, that looks like feeding on shrubs and trees to keep woodlands relatively open, as well as dispersing seeds through their dung. One 1994 study noted the ecological value of the nilgai in ravines lining the Yamuna River, where the nitrogen contained in their fecal matter can make a large difference in soil quality, particularly in hot summer months.

These creatures actually defecate strategically, creating dung piles that are thought to mark territory between dominant males. As a clever evasion tactic, these are often created at crossroads in paths through forest or savanna-scape, so that predators may not be able to trace the nilgai’s next steps so easily.

Food webs for changing times

The natural predators of the nilgai once included the Bengal tiger and Asiatic lion, as well as leopards, Indian wolves, striped hyena, and dholes (or Indian wild dogs) which sometimes prey on juveniles. However, as deforestation, habitat loss and fragmentation, and development pressures change the face of the subcontinent, the ecological role of the nilgai has become more complicated. While their association with cows, a sacred animal in Hinduism, has widely prevented nilgai from being killed by humans, the relationship between people and nilgai is becoming more contentious.

Where nilgai lack their traditional habitat to browse, they turn to plundering agricultural fields, frustrating the farmers who work so hard to cultivate these crops. Farmers in many Indian states thus consider them pests, and the state of Bihar has now classified them as ‘vermin’ and allowed them to be culled.

There’s no place like… Texas?

Strangely enough, when I got inspired by my nilgai sightings in India and decided to learn more about these Asian antelopes, one of the first search results I encountered involved nilgai populations here in the US. Specifically in Texas, an introduction of nilgai in the 1920 and 30s has spawned a population of feral roamers. Accounts say that nilgai were originally brought to the North King Ranch both for conservation and for exotic game hunting, somewhat distinct priorities that regardless led to the same result, a Texas population that now booms at over 30,000 individuals.

In this locale, nilgai largely graze grasses and crops, as well as scrub and oak forests. Here hunters have no qualms about killing them, but some animal rights groups object, and popular opinion remains divided on whether such treatment is cruelty or, well, fair game.

These days, one concern is that a large nilgai population contributes to the spread of the cattle fever tick. Another concern remains about these grazers acting as ‘pests’ on agricultural land.

Fundamentally there is a question that lies at the heart of the nilgai’s fate, both at home in India and Bangladesh, where natural predators and original habitat have steeply declined, and abroad, where they weren’t a part of the original ecosystem at all: what do you do when an animal’s ecological role is out of balance?

In my view, there are no easy answers, but a familiar pattern we seem to uncover – that healthy ecosystems, where intact, harbor more complexity than we can recreate or give them credit for. Little by little, I hope we can support their conservation and resurgence.

By Maya Dutta

Maya Dutta is an environmental advocate and ecosystem restorer working to spread understanding on the key role of biodiversity in shaping the climate and the water, carbon, nutrient and energy cycles we rely on. She is passionate about climate change adaptation and mitigation and the ways that community-led ecosystem restoration can fight global climate change while improving the livelihood and equity of human communities. She is the Assistant Director of Regenerative Projects at Bio4Climate.

Sources:

https://animalia.bio/nilgai

https://www.thedailybeast.com/nilgai-the-chimeric-beast-overrunning-texas-and-spreading-disease

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nilgai

https://www.britannica.com/animal/nilgai