What is the heaviest, oldest and one of the largest creatures on the planet?

It’s not the sperm whale, not even close. The surprising answer is PANDO!!!

You’ve never heard of Pando? Neither had I, till Paula Phipps here at Bio4Climate suggested it as a Featured Creature!

Pando is a 108-acre forest of quaking aspens in Utah, thousands of years old, in which all of the trees are genetically identical! These trees are all branches on a shared root system that is thousands of years old, so the whole forest is one single organism!

Known as the “Trembling Giant,” Pando is more than just your average arbor. It’s so unique it has a name. In a sense, Pando “redefines trees,” says Lance Oditt, who directs the nonprofit Friends of Pando (you will see his name on some of the photos in this piece). Pando also has symbolic significance to many people. Former First Lady of California Maria Shriver puts it this way: “Pando means I belong to you, you belong to me, we belong to each other.”

Lance Oditt/Friends of Pando (Wikimedia Commons)

Pando (Latin for “I spread”) is a single clonal organism, i.e., it is one unified plant representing one individual male quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides). This living organism was identified as a single creature because its parts possess identical genes with a unitary massively-interconnected underground root system. This plant is located in the Fremont River Ranger District of the Fishlake National Forest in south-central Utah, United States, around 1 mile (1.6 km) southwest of Fish Lake. Pando occupies 108 acres (43.6 ha) and is estimated to weigh collectively 6,000 tonnes (6,000,000 kg), making it the heaviest known organism on earth.

Its age has been estimated at between 10,000 and 80,000 years, since there is no way to assess it with any precision due to the irrelevance of branch core samples to the age of the whole creature. Its size, weight, and prehistoric age have given it worldwide fame. These trees not only cover 108 acres of national forestland, but weigh a shocking six million kilograms (13 million pounds). This makes Pando the most massive genetically distinct organism. However, the title for the largest organism goes to “the humongous fungus,” a network of dark honey fungus (Armillaria ostoyae) in Oregon that covers an amazing 2,200 acres. I had no idea such single living organisms could exist! I was instantaneously intrigued, and wanted to learn more about this curious entity.

(Lance Oditt/Friends of Pando)

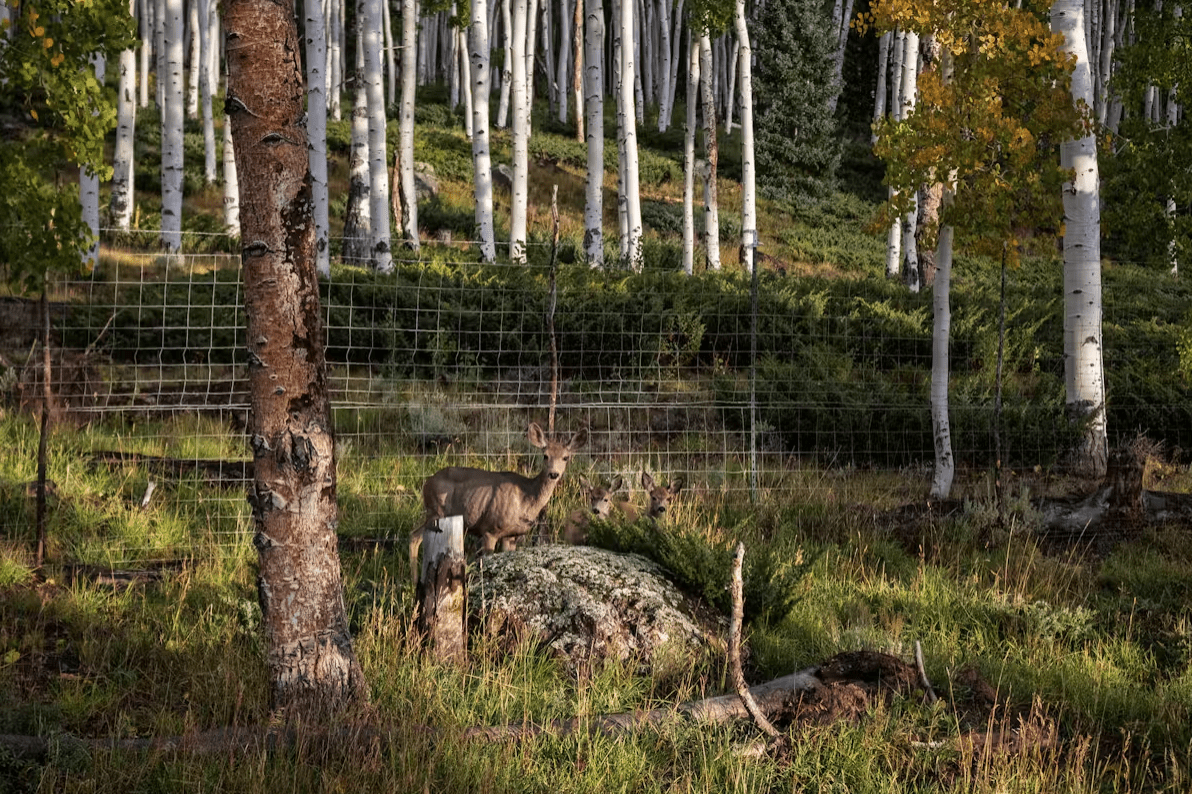

Pando is also in trouble, because older branches (since it is not composed of individual “trees” despite its appearance, but sprouts from one extensive root system) are not being replaced by young shoots to perpetuate the organism. The reason is difficult to determine, between issues of drought, human development, aging, excessive grazing by herbivores (cattle, elk and deer), and fire suppression (as fire benefits aspens). The forest is being studied, and fencing has been put up around most of the area to prevent browsing animals from entering the forest and eating up the young shoots sprouting from this unified root system. Scientists believe that both the ongoing management of this area and uncontrolled foraging by wild and domestic animals have had deeply adverse effects on Pando’s long-term resilience. Overgrazing by deer and elk has become one of the biggest worries. Wolves and cougars once kept the numbers in check of these herbivores, but their herds are now much larger because of the loss of such apex predators. These game species also tend to congregate around Pando as they have learned that they are not in any danger of being hunted in this protected woodland.

An Epic History

Despite its fame today, the Pando tree was not even identified until 1976. The clone was re-examined in 1992 and named Pando, recognized as a single asexual entity based on its morphological characteristics, and described as the world’s largest organism by weight. In 2006 the U.S. Postal Service honored the Pando Clone with a commemorative stamp as one of the “40 Wonders of America.”

Genetic sampling and analysis in 2008 increased the clone’s estimated size from 43.3 to 43.6 hectares. The first complete assessment of Pando’s status was conducted in 2018 with a new understanding of the importance of reducing herbivory by mule deer and elk to protect the future of Pando. These findings were also reinforced with further research in 2019. But Pando is constantly changing its shape and form, moving in any direction the sun and soil conditions create advantages. Any place a branch comes up is a new hub that can send the tree in a new direction. If you visit the tree and see new stems, you are witnessing the tree moving or “spreading” out in that direction.

Botanists Burton Barnes and Jerry Kemperman were the first to identify Pando as a single organism after examining aerial photographs and conducting land delineation (basically, tracking its borders). They revealed their groundbreaking discovery in a 1976 paper.

Today, perhaps the person who knows the most about Pando’s genetics is Karen Mock, a molecular ecologist at Utah State University in Logan. She and three other scientists ground the aspen’s leaves into a fine powder and then extracted DNA from the dried samples. “When we started our research, I was expecting that it wouldn’t be one single clone,” as is the case with other systems, Mock says. “I was wrong. Pando is a ginormous single clone.” They published their findings in a 2008 study. The group also confirmed that this quaking giant is male, creates pollen and constantly regenerates itself by sending new branches up from its root system in a process called “suckering.”

“The original seed started out about the same size as an aphid,” Mock says. “It’s tiny, and to think that it started this one little tree, its roots spreading and sending up suckers to become one vast single clone.” For context, Pando’s current size is about 10-11 times bigger than that!

Their research has forever changed the way that the scientific community approaches Pando and helped raise public awareness of this unique clone growing in southern Utah while providing it additional protection. For example, Friends of Pando has fixed numerous broken fences that were allowing deer access to the tree.

Pando Seed sat down in may have looked like

(Lance Oditt/Friends of Pando)

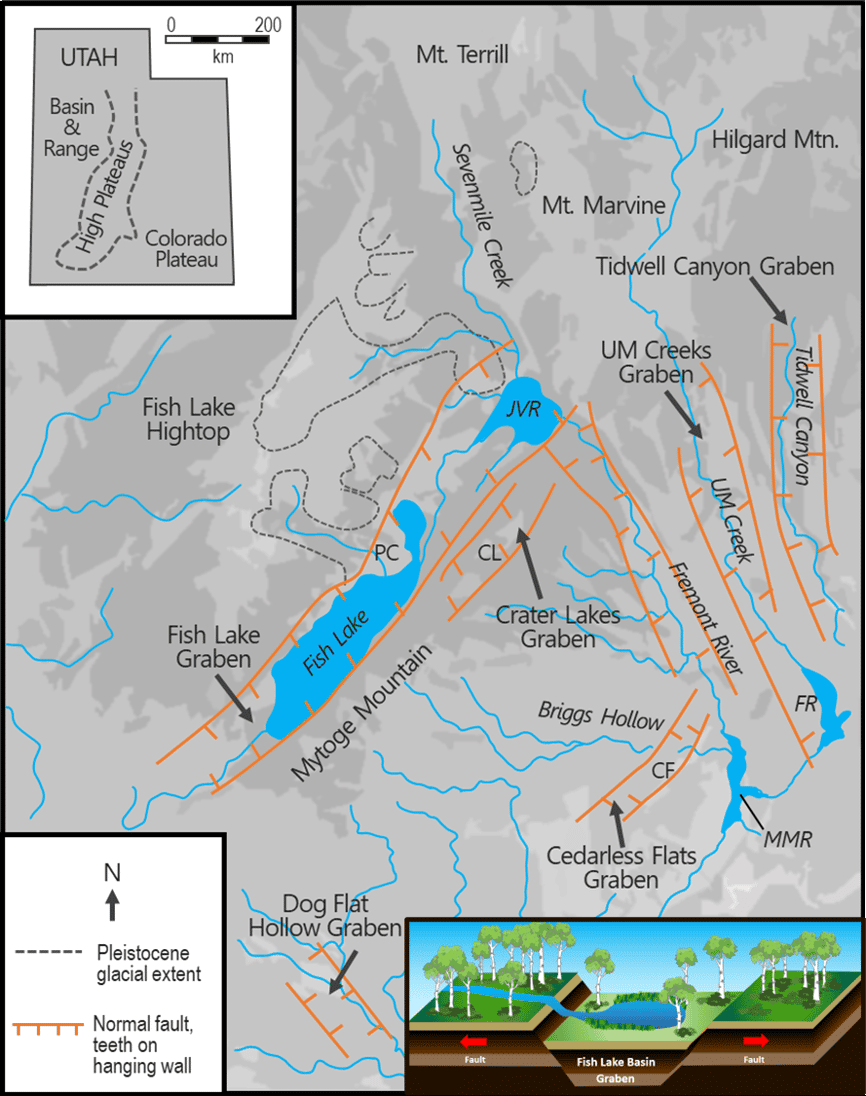

Speculating about how Pando started, biologists have woven a rough image of its early origins. They describe Pando as a tree that transcends nearly every concept of trees and natural classifications we have today. Pando is simultaneously the heaviest tree, the largest tree by land mass, and the largest quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides). A masterpiece of botanical imagination, how Pando came to be is even more improbable than the challenge of classifying it. One possibility is that on one of the first warm spring days of the year, thousands of years after the last ice age, a single Aspen seed floating 9,000 feet in the sky came to rest on the southeastern edge of the Fishlake Basin, a land littered with massive volcanic boulders, split apart along an active fault line, carved by glaciers, littered with mineral rich glacial till and shaped by landslides and torrential snow melts that continue to this day.

But what would appear to be a wasteland to the untrained eye made for a perfect home for the Pando seed. This was a prime location along the steep side of a spreading fault zone that provides water drainage to the lake below and a barren landscape with rich soil laid down by glaciers. Therefore this was a place where the light-hungry Pando seed would face no competition for sunlight. Underground, a tumultuous geologic landscape favored Pando’s sideways moving roots system over other native trees that prefer to dig down.

If we were to see the first branch of Pando, we might think nothing of it, not knowing what was in store for this organism with the ability to grow up to 3 feet per year. Those first years, any number of disasters could have destroyed the tree altogether.

In fact, for Pando to exist at all, at least one disaster likely set the tree on a new course that created the tree we know today. As a male tree, Pando only produces pollen so, to advance itself over the land, Pando has to replicate itself by sending up new stems from its root, a process called suckering. Probably at some time during those first 150 years of Pando’s life, something disrupted the growth hormones underground and within its trunk, creating an imbalance so Pando began to sucker. Although there’s no way to tell what that force was, we do know that was the moment Pando started to self-propagate, to spread both across the land and toward us in time. And today, that one tree has become a lattice-work of roots and stems that a rough field estimate indicates would conceivably be able to stretch as far as 12,000 miles or about halfway around the world.

Opinions do seem to vary on different estimates of Pando’s real weight and age. One source said Pando’s collective weight was 13 million pounds, double the estimate stated above, with the root system of these aspens believed to have been born from a single seed at the end of the last major ice age (about 2.6 million years ago). As we cannot measure Pando’s true age, we are left with intelligent guesses. This reminds me of what I often jestfully say might be an academic’s ideal state of mind, to be “unencumbered by facts or information and thus free to theorize”!

Wonder among wonders

While Pando is the largest known aspen clone, other large and old clones exist, so Pando is not totally unique. According to a 2000 OECD report, clonal groups of Populus tremuloides in eastern North America are very common, but generally less than 0.1 hectare in size, while in areas of Utah, groups as large as 80 hectares have been observed. The age of this species is difficult to establish with any precision. In the western United States, some argue that widespread seedling establishment has not occurred since the last glaciation, some 10,000 years ago, but some biologists think these western clones could be as much as 1 million years old.

Pando encompasses 108 acres, weighs nearly 6,000 metric tons, and has over 40,000 stems or trunks, which die individually and are replaced by new stems growing from its roots. The root system is estimated to be several thousand years old with habitat modeling suggesting a maximum age of 14,000 years, but others estimate it as much older than that. Individual aspen stems typically do not live beyond 100–130 years and mature areas within Pando are approaching this limit. Indeed, the worry is that there are so few younger stems surviving that the whole organism is being placed at risk. This is why the scientists are trying to restrict herbivore access to this protected area.

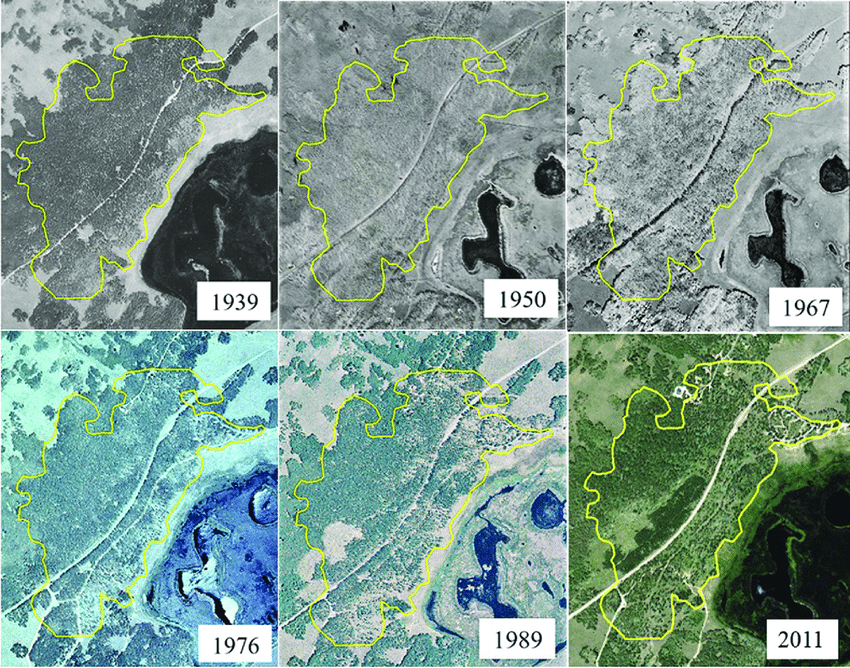

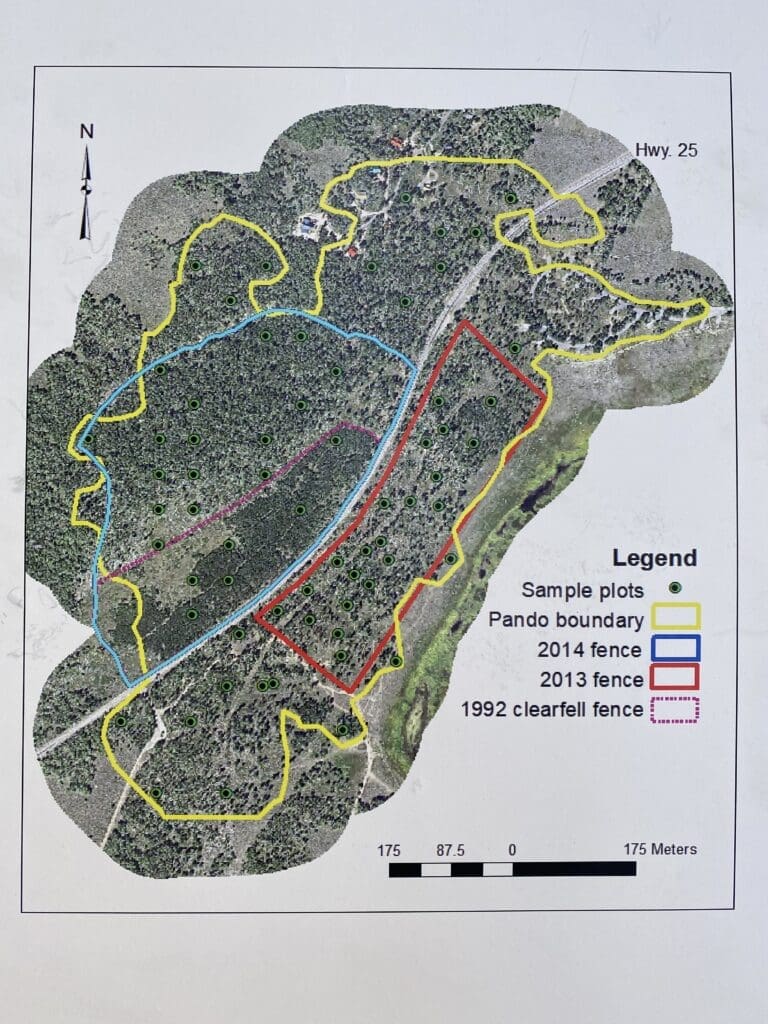

Base images courtesy of USDA Aerial Photography Field Office, Salt Lake City, Utah

This ancient giant, however, has been shrinking since the 1960s or 70s. This timing is no coincidence. As human activity has grown in the western United States, so has our impact on the surrounding ecosystems. The biggest factor behind this shrinking is a lack of “new recruits.” The shoots that form from Pando’s ancient rootstock are not making it to maturity. Instead, they are being eaten while they are still small, soft, and nutritious. Mule deer are the main culprits. Cattle are also allowed to browse in this forest for brief intervals every year, and the combined herbivory has thwarted Pando’s efforts to keep up with old dying trees.

These changes have led to a thinning of the forest. One study used aerial imagery to identify these changes, showing that Pando isn’t regenerating in the way that it should. Researchers assessed 65 plots that had been subjected to varying degrees of human efforts to protect the grove: some plots had been surrounded by a fence, some had been fenced in and regulated through interventions like shrub removal and selective tree cutting, and some were untouched. The team tracked the number of living and dead trees, along with the number of new stems. Researchers also examined animal feces to determine how species that graze in Fishlake National Forest might be impacting Pando’s health.

The problem is that with enough loss of old trees, the grove will lose its ability to regenerate. A dense forest can feed its roots with fuel from photosynthesis, and is able to send up new shoots regularly. But as it loses leaves and their photosynthetic capability, it can start to shrink.

installations to protect its growth

Image courtesy of Paul Rogers and Darren McAvoy, St. George News

As part of this new study, the team analyzed aerial photographs of Pando taken over the past 72 years (see previous image above with photos from 1939 to 2011). These impressions drive home the grove’s dire state. In the late 1930s, the crowns of the trees were touching. But over the past 30 to 40 years, gaps begin to appear within the forest, indicating that new trees aren’t cropping up to replace the ones that have died. And that isn’t great news for the animals and plants that depend on the trees to survive, researcher Paul C. Rogers said in a statement.

Fortunately, all is not lost. There are ways that humans can intervene to give Pando the time it needs to get back on track, among them culling voracious deer and putting up better fencing to keep the animals away from saplings. As Rogers says, “It would be a shame to witness the significant reduction of this iconic forest when reversing this decline is realizable should we demonstrate the will to do so.”

Though it seems easy to blame these changes on deer, the real blame still lies with us humans. Throughout the 20th century, deer populations have been hugely impacted by humans. Human impacts on ecosystems are complex and far-reaching. A major problem is the lack of apex predators in the area; in the early 1900s, humans aggressively hunted animals like wolves, mountain lions and grizzly bears, which helped keep mule deer in check. And much of the fencing that was erected to protect Pando isn’t working: mule deer, it seems, are able to jump over the fences. So we need to monitor all ecosystems to understand how they respond to human activity if we are to minimize damage, and take steps to compensate for the imbalances we create.

(Lance Oditt/Friends of Pando)

Though it is hotly contested by ranchers wanting to protect their cattle, wolf reintroduction is ongoing in the West. Hunting is also regulated by federal and state agencies, which artificially adjust deer populations. The effects of these changes are not always immediately apparent. Forest managers do their best to replicate historical levels and manage new threats.

However, we lack good historical data on herbivory in Pando or many other surrounding areas. Controlling herbivory with more hunting is one remedial option. Reduced cattle grazing in the grove has also been suggested by researchers.

Reproduction and Threats

As mentioned, the asexual reproductive process for this entity is not like that of a regular forest. An individual stem sends out lateral roots that, under the right conditions, send up other erect stems which look just like individual trees. The process is then repeated until a whole stand, of what appear to be individual trees, forms. These collections of multiple stems, called ramets, all together form one, single, genetic individual, usually termed a clone. Thus, although it looks like a woodland of individual trees, with striking white bark and small leaves that flutter in the slightest breeze, they are one entity all linked together underground by a single complex system of roots.

(Credit: Tonia Lewis)

A healthy aspen grove can replace dying trees with young saplings. As dying trees clear the canopy, more sunlight makes it to the forest floor, where young shoots can take advantage of the opening to rapidly grow. This keeps the forest eternally young, cycling through trees of all ages, as new clonal stems start growing, but when grazing animals eat the tops off newly forming stems, they die. This is why large portions of Pando have seen very little new growth.

The exception is one area that was fenced off a few decades ago to remove dying trees. This area excluded elk and deer from browsing and thus has experienced a successful regeneration of new clonal stems, with dense growth referred to as the “bamboo garden.”

Some other amazing features of Pando rise from the way aspens grow and develop. In Canada, aspen have earned the nickname “asbestos forests” as they have two unique characteristics that make them more fire tolerant. Aspen store massive quantities of water, allowing them to thwart low and medium intensity fires by simply being less flammable. They also do not create large quantities of flammable volatile oils that can make their conifer cousins so fire prone. Second, their branches reach high rather than spreading densely at the base, allowing them to avoid catching flame from fires that move over the land below.

Living where the growing season is short and winters are harsh, Pando features another advantage over other trees. It contains chlorophyll in its bark which allows it to create energy without leaves during the dark, cold winter months. Although this process is nowhere near as efficient as the energy production of the leaves in summer, this small energy boost allows Pando to get a head start by surging into bloom once temperatures reach 54 degrees for more than 6 days each spring.

However, the older stems in Pando are affected by at least three diseases: sooty bark canker, leaf spot, and conk fungal disease. While plant diseases have thrived in aspen stands for millennia, it is unknown what their ongoing ecosystemic effects might be, given Pando’s lack of new growth and an ever-increasing list of other pressures on the clonal giant, including that of climate change. Pando arose after the last ice age, so has had the benefit of a largely stable climate ever since, but that stability may be changing enough to endanger Pando’s long-term survival.

taken directly to that tree without having to navigate the entire forest virtually.

(Intermountain Forest Service, USDA Region 4 Photography

(Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Insects such as bark beetles and disease such as root rot and cankers attack the overstory trees, weakening and killing them. A lack of regeneration combined with weakening and dying trees, in time, could result in a smaller clone or a complete die-off. So the Forest Service in cooperation with partner organizations are working together to study Pando and address these issues. Over the years, foresters have tested different methods to stimulate the roots to encourage new sprouting. Research plots have been set up in all treated areas to track Pando’s progress, as foresters learn from Pando and adapt to their evolving understanding.

With regard to our changing climate, Pando inhabits an alpine region surrounded by desert, meaning it is no stranger to warm temperatures or drought. But climate change threatens the size and lifespan of the tree, as well as the whole complex ecosystem that it hosts. Aspen stands in other locations have struggled with climate-related pressures, such as reduced water supply and heat spells, all of which make it harder for these trees to form new leaves, which lead to declines in photosynthetic coverage and the continued viability of this amazing organism.

With more competition for ever-dwindling water resources (the nearby Fish Lake is just out of reach of the tree’s root system), with summertime temperatures expected to continue to reach record highs, and with the threat of more intense wildfires, Pando will certainly have to struggle to adjust to these fast-changing conditions while maintaining its full extent and size.

Age Estimates for Pando

Due to the progressive replacement of stems and roots, the overall age of an aspen clone cannot be determined from tree rings. In Pando’s case, ages up to 1 million years have therefore been suggested. An age of 80,000 years is often given for Pando, but this claim has not been verified and is inconsistent with the Forest Service‘s post ice-age estimate. Glaciers have repeatedly formed on the Fish Lake Plateau over the past several hundred thousand years and the Fish Lake valley occupied by Pando was partially filled by ice as recently as the last glacial maximum, about 20,000 to 30,000 years ago. Consequently, ages greater than approximately 16,000 years require Pando to have survived at least the Pinedale glaciation, something that appears unlikely under current genetic estimates of Pando’s age and the likely variation in Pando’s local climate.

Its longevity and remoteness have enabled a whole ecosystem of 68 plant species and many animals to evolve and be supported under its shade. However, this entire ecosystem relies on the aspen remaining healthy and upright. Though Pando is protected by the US National Forest Service and is not in danger of being cut down, it is in danger of disappearing due to several other factors and concerns, as noted above.

Estimates of Pando’s age have also been affected by changes in our understanding of aspen clones in western North America. Earlier sources argued germination and successful establishment of aspen on new sites was rare in the last 10,000 years, implying that Pando’s root system was likely over 10,000 years old. More recent observations, however, have disproved that view, showing seedling establishment of new aspen clones as a regular occurrence, especially on sites exposed to wildfire.

More recent research has documented post-fire quaking aspen seedling establishment following the 1986 and 1988 fires in Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks, respectively, where seedlings were concentrated in kettles and other topographic depressions, seeps, springs, lake margins, and burnt-out riparian zones. A few seedlings were widely scattered throughout the burns. Seedlings surviving past one season occurred almost exclusively on severely burned surfaces. While these findings haven’t led to a conclusive settling of Pando’s age, they do leave us with much to marvel over in this species’ longevity and history.

Pando’s Uncertain Future

Pando is resilient; it has already survived rapid environmental changes, especially when European settlers arrived in the area in the 19th century, and after the rise of many intrusive 20th-century recreational activities. It has survived through disease, wildfires, and too much grazing before. Pando also remains the world’s largest single organism enjoying close scientific documentation. Thus, in spite of all these concerns, there is reason for hopefulness as scientists are working to unlock the secrets to Pando’s resilience, while conservation groups and the US Forest Service are working diligently to protect this tree and its associated ecosystem. A new group called the Friends of Pando is also making this tree accessible to virtually everyone through a series of 360˚ video recordings.

If you were able to visit Pando in summertime, you would walk under a series of towering mature stems swaying and “quaking” in the gentle breeze, between some thick new growth in the “bamboo garden,” and even venturing into charming meadows that puncture portions of the otherwise-enclosed center. You would see all sorts of wildflowers and other plants under the dappled shade canopy, along with lots of pollinating insects, birds, foxes, beaver, and deer, all using some part of the rich ecosystem created by Pando.

In the summer the green, fluttering leaves symbolize the relief from summer’s heat that you get coming to the basin. In autumn the oranges and yellows of the leaves as they change color give a hint of the fall spectacular that is the Fish Lake Basin. All this can give us a renewed appreciation of how all these plants, animals, and ecosystems are well worth defending. And with respect to Pando, we can work to protect all three.

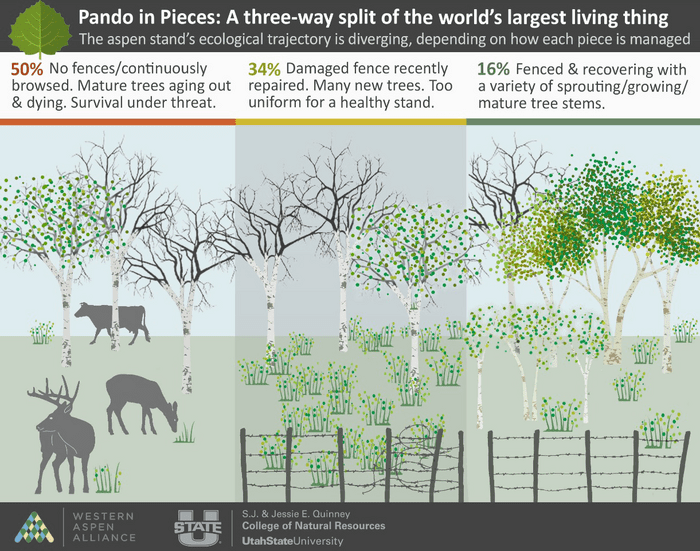

But attempts to do so have had some surprising consequences that were quite unexpected. When land managers, recognizing the stress that Pando was under from herbivores, fenced off one part of the stand to protect it from browsing, they split the grove into three parts: an unfenced control zone, an area with a fence erected in 2013, and another area that was first fenced in 2014. The 2014 fence was built from older materials to save money. This fence quickly fell into disrepair, such that mule deer could easily get around it until it was repaired in 2019. As a result, though they did not design it this way, managers had effectively created three treatment zones: a control area, a browse-free zone, and an area that experienced some browsing between 2014 and 2019. Unfortunately, these good intentions confused Pando. In 2021, it appeared that Pando was fracturing into three separate forests. With only 16 percent of the fenced area effectively keeping out herbivores, and over half of Pando without fencing, a single organism was effectively cut into 3 separate parts and exposed to varying ecological pressures.

Credit: Infographic Lael Gilbert

Bottom of Form

As Rogers explained, “Barriers appear to be having unintended consequences, potentially sectioning Pando into divergent ecological zones rather than encouraging a single resilient forest.” So not only does the stubborn trend of limited stand replacement persist in Pando, but by applying three treatments to a single organism, we also encouraged it to fracture into three distinct entities. The stumble makes sense; it is hard to understand whether fencing will work unless we compare the treatment to a control group. But the strategy does show our failing to understand Pando as one entity. After all, we would not apply three treatments to a single human. These surprising outcomes fuel vital learning experiences for researchers.

Furthermore, it may be that fencing Pando is not a solution to its regeneration problems. While unfenced areas are rapidly dying off, fencing alone is encouraging single-aged regeneration in a forest that has sustained itself over the centuries by varying growth. While this may not seem critical, aspen and understory growth patterns at odds from the past are already occurring, said Rogers. In Utah and across the West, Pando is iconic, and something of a canary in the coal mine.

As a keystone species, aspen forests support high levels of biodiversity—from chickadees to thimbleberry. As aspen ecosystems flourish or diminish, myriad dependent species follow suit. Long-term failure for new recruitment in aspen systems may have cascading effects on hundreds of species dependent on them.

Additionally, there are aesthetic and philosophical problems with a fencing strategy, said Rogers. “I think that if we try to save the organism with fences alone, we’ll find ourselves trying to create something like a zoo in the wild,” said Rogers. “Although the fencing strategy is well-intentioned, we’ll ultimately need to address the underlying problems of too many browsing deer and cattle on this landscape.”

Pando’s Songs?

“Microphones attached to Pando”. Photo Credit: Jeff Rice

Lance Oditt, Executive Director of Friends of Pando, is always searching for better ways to get his head around a tree this enormous. And he started wondering: “What would happen if we asked a sound conservationist to record the tree? What could a geologist, for example, learn from that, or a wildlife biologist?” So, Oditt invited sound artist Jeff Rice to visit Pando and record the tree.

“I just dove in and started recording everything I could in any way that I could,” says Rice, after making his pilgrimage to the mighty aspen. Rice says his sound recordings aren’t just works of art. “They also are a record of the place in time, the species and the health of the environment,” he says. “You can use these recordings as a baseline as the environment changes.” The wonders of science and curiosity never cease, do they?

In mid-summer, the aspen’s leaves are pretty much at their largest. “And there’s just a really nice shimmering quality to Pando when you walk through it,” says Rice. “It’s like a presence when the wind blows.” So that’s what Rice wanted to capture first — the sound of those bright lime green leaves fluttering in the wind. He then attached little contact microphones to individual leaves and was treated to a unique sound in return. The leaves had “this percussive quality,” he says. “And I knew that all of these vibrating leaves would create a significant amount of vibration within the tree.” Rice then set out to capture that tree-wide vibration in the midst of a thunderstorm. “I was hunkered down and huddling, trying to stay out of the lightning. When those storms come through Pando, they’re pretty big. They’re pretty dramatic.” All that wind blowing through the innumerable leaves offered Rice a sonic opportunity to record the tree.

A hydrophone was placed in contact with the roots of a tree (or “stem”) in the Pando aspen forest in south-central Utah. The sound captures vibrations from beneath the tree that may be emanating from the root system or the soil. The recording was made during a July 2022 thunderstorm and represents perhaps millions of aspen leaves trembling in the wind. It was made by Jeff Rice as part of an artist residency with the non-profit group Friends of Pando. Rice gives special thanks to Lance Oditt for his help in identifying recording locations, including the mysterious “portal to Pando.”

“We found this incredible opening in one of the [stems] that I’ve dubbed the Pando portal,” he says. Into that portal, he lowered a mic until it was touching the massive tangle of roots below. “As soon as the wind would blow and the leaves would start to vibrate,” Rice says, “you would hear this amazing low rumble.” The vibrations, he says, were passing through Pando’s branches and trunks into the ground. “It’s almost like the whole Earth is vibrating,” says Rice. “It just emphasizes the power of all of these trembling leaves, the connectedness, I think, of this as a single organism.” Rice and Oditt presented these recordings at an Acoustical Society of America meeting in Chicago.

“Field Technicians Rebekah Adams and Etta Crowley take vegetation measurement under Pando, the world’s largest living organism. A recent evaluation of the massive aspen stand in south-central Utah found that Pando seems to be taking three disparate ecological paths based on how the different segments are managed.” Credit: Paul Rogers

“This is the song of this ecosystem, this tree,” says Oditt. “So now we know sound is another way we can understand the tree.” In fact, the recordings have given Oditt research ideas, like using sound to map Pando’s labyrinth of roots. But above all, they’re a sonic snapshot of this leviathan at this moment in time. “We have to keep in mind,” says Oditt, “that it’s been changing shape and form for like 9000 years. I call it the David Bowie problem. It’s constantly reinventing itself!” And now, we’ve turned up the volume to hear Pando as the baritone soloist it has always been.

Pando as Teacher and Metaphor

Pando is seen as an inspiring symbol of our connectedness, in many engaging statements found here. I put just a few of them below, to give you the idea of how various people have reacted to Pando and its potential significance.

From The Rev. Ed Bacon, Former Senior Rector, All Saints Church, Pasadena, and Board Member, Pando Populus:

“‘We are already one but we imagine that we are not.’ Thomas Merton said those words just before his accidental death. A few months earlier in 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King in his last Sunday sermon notes that the ‘universe is constructed’ in an interdependent way: my destiny depends on yours. If there is one truth that will see us through whatever threats and chaos lie before us, it is that there will be no future without policies and attitudes based in the kind of Oneness we see in the one-tree Forest, Pando.”

From John B. Cobb, Jr., Member, American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and Board Chair, Pando Populus:

“The one-tree forest we call Pando is a community. The health and well-being of every tree contributes to the whole of the root system and lives from it. But does it make sense today for Pando to be the symbol of what we aspire to in this country, when there are such intense political feelings and competing fears? Yes, it is in just such circumstances that seeking community is most important. If you are in any of the country’s opposing camps, you can begin by formulating the way people in other camps view the world and you. You do not have to agree. But if you understand why so many people feel so disturbed and even threatened by you and your values and beliefs, you have the beginning of community. Even that beginning might save us from the worst.”

From Paul Rogers, Chief Scientist for the Pando Aspen Clone and Director of the Western Aspen Alliance:

“In recent decades resource misuse – comorbid to a warming planet – have left a long-thriving colossus gasping for breath. In Pando, as in human societies, it is easy to forget vital relations between individuals and communities. Impulses are shared as mortality portends rebirth. Vast root networks maintain a single immense colony: e pluribus unum. Pando’s 47,000 stems with enumerable variation remain linked by DNA. Humans, though genetically distinct, are joined by need, desire, and innate dependence on Mother Earth. Pando’s paradox implores us to mutually foster communities and individuals. He is the trembling giant. She is the nurturing spring.”

From Devorah Brous, environmental consultant:

“To foster wholesale systems change, go to the roots. We gather in a sacred grove and branch out to feed shared roots – as descendants of colonizers and the colonized. We break bread as formerly enslaved peoples and enslavers, as immigrants, as indigenous peoples, as refugees. As ranchers and vegans. As scientists and spiritualists. As non-binary changemakers, and established clergy. As creatives, pioneers, and politicians. To study the known and unknown teachings of the trees – we sit still under a canopy of stark differences and harvest the nature of unity. We quest to feed and water a dying tree of life.”

* * * * *

I’ve written such a lengthy piece about Pando because it has so many fascinating and unusual characteristics. Who could ever imagine all the wondrous things that Nature creates? I think Her endless spontaneity in developing biodiverse life-forms is a truly intriguing phenomenon that motivates so many of our ‘Featured Creature’ essays. And exploring them is such an interesting process. We learn new aspects of Nature’s mysteries every time. Perhaps Pando has additional lessons for us as well!

So let us continue to root for this amazingly unified tree named Pando…

Fred

Fred is from Ipswich, MA, where he has spent most of his life. He is an ecological economist with a B.A. from Harvard and a Ph.D. from Stanford, both in economics. Fred is also an avid conservationist and fly fisherman. He enjoys the outdoors, and has written about natural processes and about economic theory. He has 40 years of teaching and research experience, first in academics and then in economic litigation. He also enjoys his seasonal practice as a saltwater fly fishing guide in Ipswich, MA. Fred joined Biodiversity for a Livable Climate in 2016.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pando_%28tree%29

https://www.sciencealert.com/worlds-largest-organism-is-slowly-being-eaten-scientist-says

https://www.nationalforests.org/blog/unforgettable-experiences-pando-aspen-clone

https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/fishlake/home/?cid=STELPRDB5393641

https://www.npr.org/2023/05/10/1175019538/listen-to-one-of-the-largest-trees-in-the-world

https://pandopopulus.com/pando-the-tree/

https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2023-04-08/the-ancient-aspen-grove-called-pando-is-shrinking-can-humans-save-it

https://www.stgeorgeutah.com/news/archive/2021/08/10/ajt-friends-of-pando-capture-the-worlds-largest-organism-in-first-of-its-kind-photo-survey/

https://news.mongabay.com/2020/06/conservation-insights-from-an-enormous-aspen-clone-qa-with-ecologist-paul-rogers/

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/17/science/pando-aspens-utah.html

https://toposmagazine.com/trees-pando/

https://toposmagazine.com/trees-pando-part-two/ https://toposmagazine.com/living-giant-part-3/ https://toposmagazine.com/living-giant-part-4/

https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/articles/2018-06-28/fences-might-help-save-utahs-pando-aspen-grove

https://www.livescience.com/61116-mule-deer-are-eating-pando.html

https://gizmodo.com/earth-s-heaviest-organism-could-be-eaten-to-death-by-de-1820799676

https://www.sltrib.com/news/2017/11/11/utahs-pando-aspen-grove-is-the-most-massive-living-thing-known-on-earth-it-may-die-soon/

https://pandopopulus.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/NatHist_Rogers_2016.pdf

https://pandopopulus.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/tremblings_vol6.pdf

https://www.cityweekly.net/utah/devastated/Content?oid=2305453&showFullText=true

https://pandopopulus.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/aspen_forest.pdf

https://www.earth.com/news/pando-oldest-organisms/?placement=&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIzcezytWT_wIVHiqzAB1eJgvPEAAYAiAAEgLPBfD_BwE

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/pano-one-worlds-largest-organisms-dying-180970579/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/the-worlds-largest-tree-is-ready-for-its-close-up-180981128/

https://www.sciencefriday.com/segments/listen-to-the-pando-largest-tree/

https://www.sciencefriday.com/articles/picture-of-the-week-pando-one-of-earths-largest-living-organisms/

https://www.earthdate.org/files/000/002/104/EarthDate_162_C.pdf

https://bigthink.com/life/pando-largest-organism-stopped-growing/

https://phys.org/news/2022-09-pando-pieces-breach-world-largest.html

https://www.friendsofpando.org/

https://www.friendsofpando.org/faq1pando101/

https://www.friendsofpando.org/faqhowpandoworks/

https://www.friendsofpando.org/what-is-pando/

https://www.friendsofpando.org/the-pando-tree-2/geologic-history-fishlake/

https://www.friendsofpando.org/the-pando-tree-2/land-management-pando/

Videos:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i5fjSBj5C9I

https://utopiatvseries.com/portfolio/episode20/

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/earths-most-massive-living-thing-is-struggling-to-survive

https://www.ecosystemsound.com/beneath-the-tree

https://www.stgeorgeutah.com/news/archive/2021/08/10/ajt-friends-of-pando-capture-the-worlds-largest-organism-in-first-of-its-kind-photo-survey/ (with VIDEO of 2:22 minutes)