Have you ever heard of a squirrel that barks?

Let me introduce you to the Prairie Dog.

Sometimes, when walking alone in the high grasslands of the Western United States, you may feel as if you are being watched.

My first encounter with prairie dogs in the wild occurred as I stood in an empty prairie just outside of Badlands National Park in South Dakota. As I meandered along, minding my own business, dozens of furry creatures with beady little eyes appeared, propped themselves up on their hind legs, and began to follow my every step. Prairie dogs are adorable, it is true, but when you see a dozen spread out, standing upright, watching you intently, it can be a bit disconcerting.

They were, however, no threat, and weren’t eyeballing me just to judge me. A prairie dog standing on his hind legs – “periscoping” as it is known – is simply keeping watch for predators. And their distinctive bark? It may sound like “yip,” but it is actually a sophisticated language developed over thousands of years that is still not fully understood by scientists.

Prairie dog barks convey everything about a predator’s size, speed, and location. According to a study at the University of Northern Arizona led by Con Slobodchikoff, Ph.D (see video linked below) pitch, speed, and timbre were all altered in a consistent manner corresponding to the species of predator and the characteristics of each. Certain “yips” could even be interpreted to represent nouns (the threat is “human”), verbs (the “human” is moving toward us), and adjectives (the “human” is wearing an ugly yellow shirt). So now that I think about it, I guess they were judging me, and I am not sure how I feel about that. But still, those are some impressive squirrels.

Wait, did you say squirrels?

Yes.

Squirrels. From the Sciuridae family. Prairie dogs are marmots (or ground squirrels) that bark like a dog, prompting Lewis and Clark to label them “barking squirrels,” which may lack points for creativity but is at least more accurate than calling them “dogs.” Prairie dogs, in fact, have no connection to dogs whatsoever.

There are five major species of prairie dog, who all live in North America at elevations between 2,000 and 10,000 feet. The Black-Tailed prairie dog covers the largest territory, filling an extensive region from Montana to Texas. Gunnison’s prairie dogs occupy the southwest near the Four Corners region. White-Tailed prairie dogs reside in Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado. Mexican and Utah prairie dogs belong to Mexico and Utah, respectively, and both are considered endangered.

As you may have observed, prairie dogs live in areas prone to harsh extremes of weather. To protect themselves, they dig extensive burrow networks with multiple entrances, designed to create ventilation, route flood water into empty chambers deep underground, and keep watch for predators. Their burrows connect underground, organized into sections called “coteries,” each of which contains a single-family unit responsible for the maintenance and protection of their area. Multiple coteries become “towns” of startling size and complexity. According to the National Park Service, the largest prairie dog town on record covered 25,000 square miles, bigger than the state of West Virginia!

That IS an impressive squirrel.

Indeed.

Over the years, however, the prairie dog’s range has shrunk, scientists estimate, by as much as 99%, largely because of agriculture. Farmers and ranchers tend to regard prairie dogs as a nuisance, as they sometimes eat crops (they are mostly herbivores) and their holes create a hazard for livestock. They will bulldoze their towns or conduct contest kills to remove them, which has had devastating impacts.

Experts consider prairie dogs to be a keystone species. Their loss affects hundreds of other species who rely on them for food or use their burrows for shelter. They are instrumental in recharging groundwater, regulating soil erosion, and maintaining the soil’s level of production. Prairie dog decline, in fact, eventually leads to desertification of grassland environments.

So, an impressive AND important squirrel?

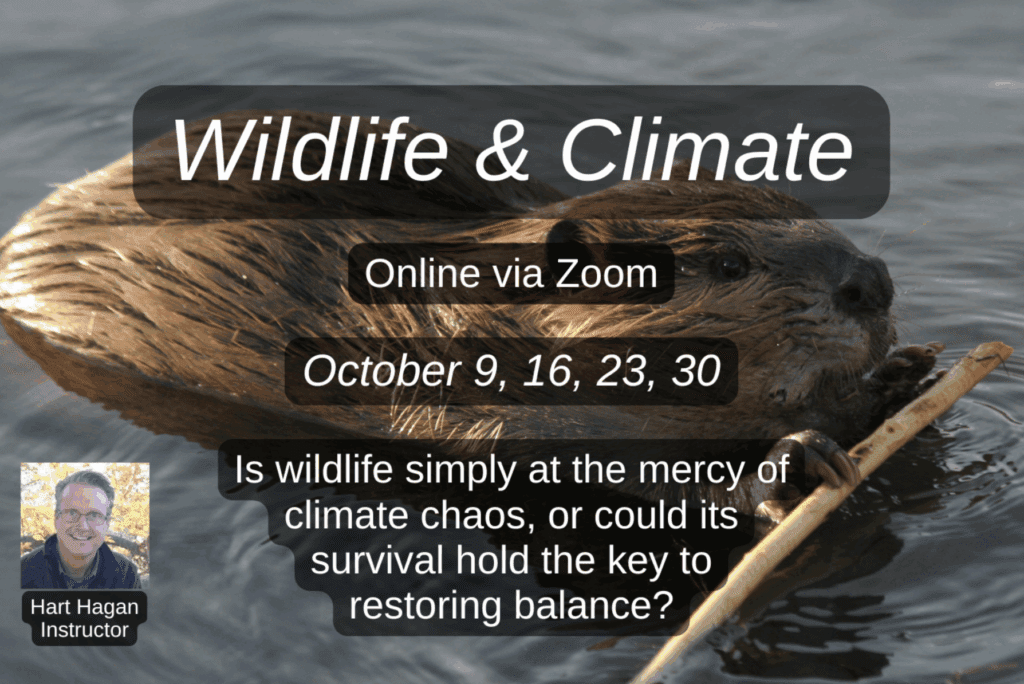

Yes, and the restoration of prairie dog habitats could be a crucial step in mitigating the effects of climate change.

If you’ve caught prairie dog fever, dive deeper into the resources below. And to learn more about Prairie Dog language, check out this fascinating video:

Hoping one day to converse with my personal prairie dog army,

Mike

Mike Conway is a part-time freelance writer who lives with his wife, kids, and dog Smudge (pictured) in Northern Virginia.

Sources:

https://animals.net/prairie-dog/

Prairie dog – Wikipedia

https://www.humanesociety.org/resources/what-do-about-prairie-dogs

Prairie Dog Decline Reduces the Supply of Ecosystem Services and Leads to Desertification of Semiarid Grasslands | PLOS ONE

Prairie Dogs | National Geographic

Prairie Dogs: Pipsqueaks of the Prairie (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov)