What species fights climate change, creates “surface-active groups,” and shares a home with the Maine lobster?

Image credit: NOAA

That would be the North Atlantic right whale. Hardly an unsung species, this large marine mammal is one of the most critically endangered in the world, with approximately 372 members remaining. Unfortunately for the whale, its story is inexplicably intertwined with that of North Atlantic fishermen, in particular the Maine lobster industry. On the surface, this is a battle between said industry and whale conservationists. But must this story be a zero-sum game?

A Deep Dive

As one of the largest species on the planet, the North Atlantic right whale can grow up to 14-17 meters long and weigh up to 154,000 pounds. During my research, I was surprised to find that there are three subspecies of right whale, which appear very similar but have lived in genetic isolation for millions of years. In addition to the North Atlantic right whale, there are the North Pacific and South Atlantic right whale species. All three are listed as “Endangered” under the US Endangered Species Act (ESA), a designation that triggers various types of protective legislation. While the North Pacific right whale fares about as well as the North Atlantic under these conditions, estimates of the South Pacific right whale population are as high as 4,000.

Despite their formidable size, the right whale is a gentle giant. They are incredibly slow swimmers, and can reach swimming speeds of

They also use their baleen to filter their food and have diets mainly consisting of copepods. This diet is also part of the whale’s role as a “nutrient cycler” in the ocean ecosystem: by feeding and defecating, the whales provide crucial nutrients to phytoplankton, which helps sequester atmospheric carbon– hence their role as a climate change fighter!

Right whales are also incredibly social creatures and are often seen vocally interacting on the surface of the ocean in both mating and social settings. These interactions are called surface active groups (SAG), and make for great whale watching. Analogously, the speed, size, and behavior of the right whale led to its persecution by whale hunters for centuries. These actors even named the species, as they were the so-called “right whale” to hunt. The slow-moving, blubber-rich, and surface-active North Atlantic right whale was thus hunted to near extinction several times in history. The first concrete step toward whale protection at an international level occurred in 1946, when the United Nations established the still-active International Whaling Commission.

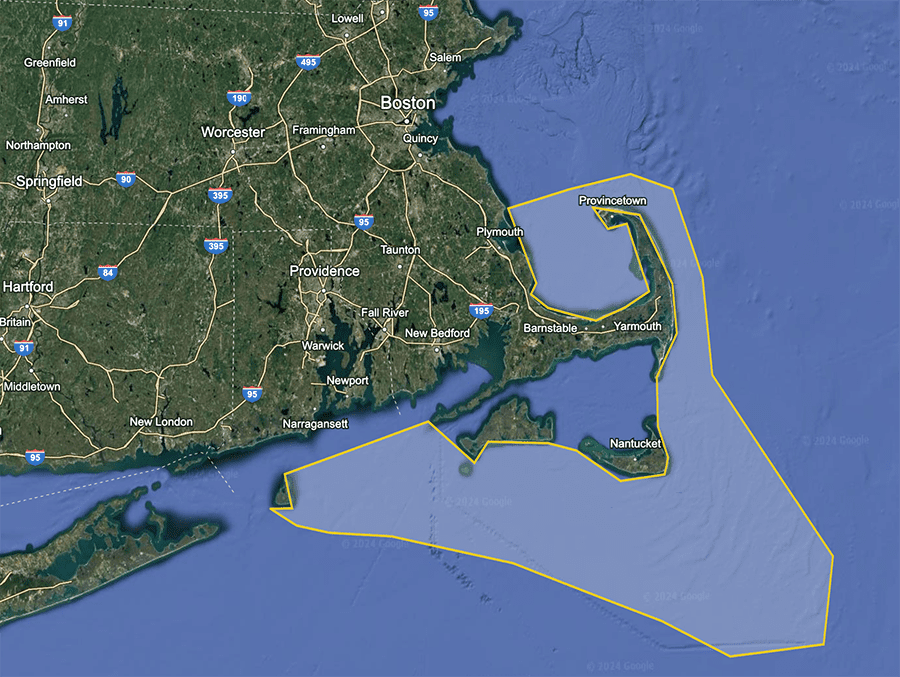

The North Atlantic right whale commonly resides on the east coast of the United States and the west coast of Europe. In the states, the whale is known for feeding in the north (especially by Cape Cod and the Gulf of Maine) and calving in the south near Georgia. Afterward, the mothers herd their calves north so they can benefit from the plentiful copepods off the coast of Massachusetts.

It would be a mistake, however, to assume that right whales are entirely bound to such human-mapped migration patterns. This was pointed out to me by Rob Moir of the Ocean River Institute (ORI), who showed me examples of whales breaking these patterns. Notably, the ORI reported an instance of two female right whales, Curlew and Koala, migrating as far south as the Bahamas and as far north as Prince Edward Island.

This outlier displaying whale intelligence reminded me of a larger point that my professors often make, that discourse around environmental protection sometimes falls into the trap of framing such actions as benevolence on our part. In reality, we share this planet with complex, intelligent species and natural processes, and it is in our best interest to preserve them. I believe wholeheartedly in the importance of functional natural systems. As someone born and raised in Maine, my public school education was full of cautionary tales of how anthropogenic changes can destabilize human lives.

In Maine, we have a long history of learning from unsustainable economic systems the hard way.For better or worse, many livelihoods here are tied to the functionality of our natural resources. In the early 1990s, Atlantic cod stocks virtually collapsed after decades of overfishing. Similar results in the shrimp, halibut, and numerous other populations led many to move into the lobstering industry. Beyond massive job losses, these shifts were particularly painful in a state whose cultural identity rests on continuing these ways of

Lobster vs. Whale

The Maine lobster industry faces numerous threats to its well-being, including legal gains in right whale conservation. In many ways, the continuance of the Maine lobster industry is a bit of a miracle: it is a vintage way of life, an occupation only made possible by stringent and consensual regulations designed to limit overfishing. The catching of egg-laying female lobsters is prohibited, and limits on the minimum size allowed for a harvested lobster are routinely updated. Hauling times are also limited during the summer months, and hauling is prohibited after sunset from November through May. These efforts become more important in the face of lobster northward migration to the Bay of Fundy. The Gulf of Maine is warming faster than 99% of the world’s oceans, creating increasingly less suitable lobster conditions.

When you look at the numbers, the importance of the lobster industry in Maine becomes clear. Estimates from a 2019 Middlebury College study report that the seafood sector provided as many as 33,000 Maine jobs and $3.2 billion in revenue in Maine annually. Although these numbers have since decreased, they stand to represent the strong presence of moneyed interests in the fight against right whale conservation, but also that the livelihoods of ordinary Mainers and New Englanders are at stake. Under these pressures, lawmakers are undoubtedly tempted to side with economic progress over conservation, which begs the question…

What Rights Do Whales Have?

In 1973, the United States government passed the Endangered Species Act (ESA), which holds the federal government responsible for the conservation of species classified as threatened or endangered by the US agencies. In article (a)(1)of Section II, the ESA asserts that species loss is a “consequence of economic growth and development untempered by adequate concern and conservation.” Thus, the framers of this document intended this law to empower the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), and successful plaintiffs to defend endangered animals against economic interests.

But what, exactly, is the monetary value of a given species on this planet? The 1978 court case Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) v. Hill, which was the Supreme Court’s first exercise in interpreting the ESA, explored this question. The plaintiff was second-year Tennessee University Law student Hiram Hill, who sued the TVA to halt the construction of the Tellico Dam. The dam was set to bring immense economic benefits to the area, but would also render the snail darter, a small, endangered fish residing in the ESA-designated critical habitat of the Tennessee River, extinct.

Courtesy Tennessee Valley Authority

Initially, the courts sided with the TVA. The District Court claimed that protecting the snail darter would create “an unreasonable result,” essentially, that the existence of the snail darter was not worth the price of halting the dam’s construction. Unfortunately for the TVA, such an exemption is not provided for in the ESA. SCOTUS saw this and reversed earlier rulings, siding with Hill. This ruling was not obeyed by Congress, however. A few years later, a small amendment authorizing the TVA to complete the Tellico Dam was thrown into an unrelated bill, which became law. This was illegal and violated SCOTUS’s authority.

At this point, you may be asking what a fifty-year-old court case about a freshwater fish (which did not go extinct, by the way) has to do with the right whale. The answer is quite a bit. In court, the snail darter faced off with the Tellico Dam for the right to exist, with the former providing no major economic benefit and the latter with grand claims that it would. In the end, the fight was not defined by this metric- instead, the highest court in the United States ruled that all species have a right to exist that is monetarily immeasurable.

Source: NOAA

The Blame Game

The necessary solutions for right whale survival will be disruptive. Organizations such as Oceana name the two biggest threats to right whales as vessel strikes and entanglements with ropes used in fishing equipment (despite decades-old Maine laws mandating weak links and sinking lines to limit whale entanglements). Regarding the latter, the most productive lobster season in Maine and Massachusetts coincides with the right whale’s food-motivated pilgrimage to the same waters. NOAA first officially connected the lobster industry to right whale deaths in 1996 and recommended seasonal prohibitions on fishing.

In 2017, NOAA recorded an “Unusual Mortality Event” where 17 right whales died, many due to fishing gear entanglements. This event spurred many of the modern “whale versus lobster” legal battles and debates we see today. In 2022, U.S. representatives in Congress secured a six-year pause on legislating the lobstering industry in the way of whale conservation, citing a history of sustainable practices in the industry. As a compromise, the bill featured forensic gear-marking requirements and authorized funding for whale-safe ropeless traps. These trap technologies today remain unreliable, despite extra funding.

The Right Way Forward

What elements define a sustainable policy? In this case, the answer isn’t black and white: it’s not pro-whale or pro-lobster industry. On one hand, the ESA asserts that the North Atlantic right whale has the right to live. On the other hand, the hardships that the lobster industry currently faces are not the result of poor choices made by the industry itself. Climate change is the fault of larger societal processes and decisions, and the lobster fishermen of Maine have long been careful to maintain the size of the local lobster population. As for sustainability in the way of right whales, ropeless traps aren’t currently reliable enough for commercial use: fortunately, the industry has until 2028 to make them so.

In the meantime, whale conservationists see other solutions to protect the North Atlantic right whale populations. For example, the Ocean River Institute advocates for a designated right whale sanctuary off the coast of Massachusetts. This area, which is already a desirable feeding area for right whales, would be administered by a diverse advisory council of interested parties, including scientists and representatives of the fishing industry. If the area in question were to become designated under the National Marine Sanctuaries Act, fishing of any kind would include restrictions on commercial fishing and types of gear.

Ocean River Institute

Furthermore, the ORI sees the planting of Miyawaki forests in Massachusetts coastal towns as a tool to improve the lives of right whales. Beyond causes of mortality, whales suffer when polluted stormwater enters their habitat. This process can lead them to ingest pollutants that cause illness and infections. Additionally, contaminated stormwater can cause algae blooms and deplete the nutritional quality and availability of copepods. One way to limit stormwater runoff into the ocean is to create land conditions where water can be absorbed. Miyawaki forests are excellent at this task: their loose soil and dense vegetation (which is meant to mimic an old-growth forest for rapid plant growth) is perfectly suited to absorb large amounts of water. This could improve conditions for right whales off the coast of Massachusetts and beyond.

As a self proclaimed “policy person,” the lack of legislative progress on climate and conservation issues is incredibly frustrating. I also believe that the government owes a fair solution to the lobster industry. Delivering justice in this situation would therefore be a complex process- fortunately, we can initiate and foster change at an individual level.

**Special thanks to Rob Moir (Ocean River Institute) and Taylor Mann (Oceana) for providing information for this piece!

Alexa Hankins is a student at Boston University, where she is pursuing a degree in International Relations with a concentration in environment and development policy. She discovered Bio4Climate through her research to develop a Miyawaki forest bike tour in greater Boston. Alexa is passionate about accessible climate education, environmental justice, and climate resilience initiatives. In her free time, she likes to read, develop her skills with houseplants, and explore the Boston area!

Dig Deeper

- Call for the Right Whale National Marine Sanctuary

- UN Commission Opens an Investigation Against the US for Lack of Right Whale Action

- Petition: Conservation Law Foundation

- Petition: Oceana

- Petition for the Right Whale National Marine Sanctuary: Ocean River Institute