I’m smaller than dust, yet ancient and wise,

I thrive in the harshest of lows and highest of highs.

No mate, no death, no fear of the cold,

I borrow new genes when my own get too old.

Image by Frank Fox

Our world follows certain rules. Or at least, that’s what I was taught growing up. Falling objects accelerate at 9.8 meters per second squared in a vacuum. Warm air rises. Diagonally cut sandwiches just taste better. Living things, too, evolve a certain way, survive a certain way, die a certain way.

Or so I thought, anyway.

I was not taught that there are some creatures out there that cheat death, that rewrite their own DNA and survive in conditions that should render said survival impossible. At a moment when humans are trying to hack biology in an effort to live younger, longer, there are creatures out there that have been doing it for millions of years.

Meet the rotifer.

You’ve probably never seen one, but they’re everywhere: in puddles, moss, soil, and freshwater lakes. They look like something from Pandora, spinning through water with wheel-like cilia. Hardly larger than a speck of dust, they don’t roar, they don’t tower over landscapes, and they’re not exactly at the top of any food chain as I know them. But they’ve outlived entire species, survived mass extinctions, and continue to defy the rules of biology we thought we knew.

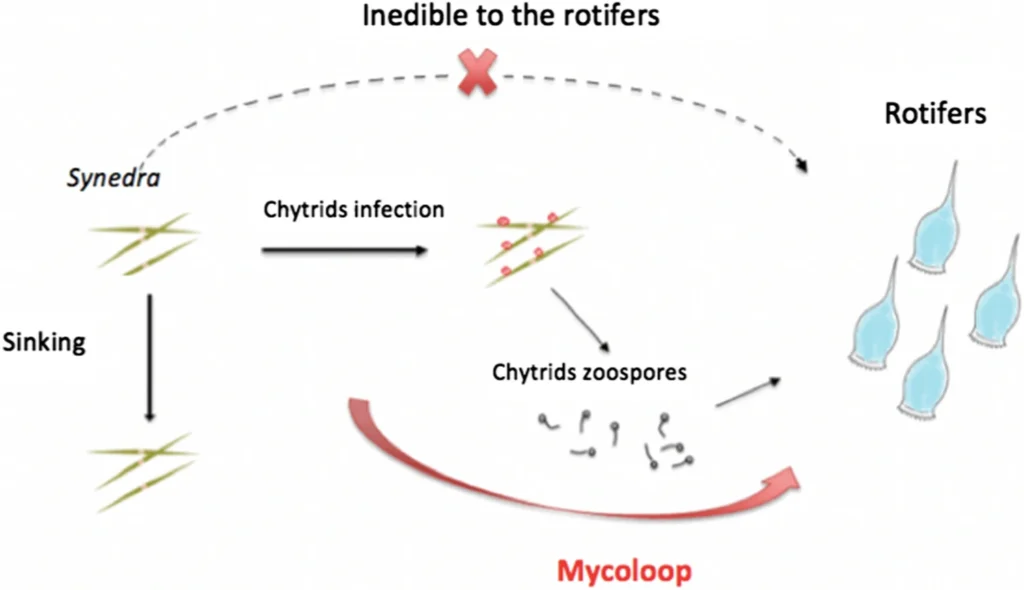

While rotifers may be practically invisible to our eyes, their impact is not. They play a fundamental role in freshwater ecosystems, drifting through aquatic environments and feeding on algae, bacteria, and other organic debris. Remember my little quip earlier about food chains? Well, it’s sort of a half-truth. They feed on algae, bacteria, and bits of organic debris—basically whatever’s floating around at the microbial level. In doing so, they turn microscopic life into something usable for everything else. They’re one of the first stops in the food web, sustaining creatures far bigger than themselves. Take them out, and the whole darn thing starts to wobble.

Life is full of exceptions, and even the smallest creatures can upend our understanding of what survival, and life itself, really means.

Rule #1: It Takes Two to Tango

A fundamental principle of biology I thought I understood is that species need genetic diversity to evolve and survive. Sexual reproduction is nature’s way of mixing genes, creating stronger offspring that are better adapted to changing environments. Without this reshuffling of DNA, plant and animal species alike face genetic stagnation and, over time, possibly extinction.

Rotifers see it differently.

For tens of millions of years, the bdelloid class of rotifer has lived without sex. They reproduce by cloning themselves over and over, spawning genetically identical offspring generation after generation.

By my logic, this should have led to their extinction long ago. They should have faced great difficulty adapting to changing environments, vulnerable to disease, and trapped in a state of evolutionary stasis. Instead, they’ve flourished.

But how?

By stealing DNA from other organisms. Instead of relying on traditional sexual reproduction, bdelloid rotifers are actually able to absorb genetic material from bacteria, fungi, and even some plants. This process, known as horizontal gene transfer, allows them to patch together their own genes with foreign DNA, essentially hijacking useful traits from unrelated life forms.

It’s a complicated process that, to be honest, I don’t fully understand. But that’s okay, because neither do the scientists studying this stuff. Here’s what they think is happening.

When a bdelloid rotifer dries out (usually in a harsh environment), its DNA begins to crumble and break apart into pieces. When it rehydrates, something strange happens: its cell walls become more permeable, just enough to let in snippets of DNA floating nearby, bits from bacteria, fungi, even plants. Once inside, the rotifer’s cellular machinery picks them up and patches them into its own fragmented genome. It’s like a genetic repair job using whatever foraged parts are lying around. Instead of mixing genes through sex, bdelloids build their genetic diversity by borrowing from the world around them. It’s a little messy, a little miraculous, but it works.

Image Credit: Virginia Sánchez Barranco, et al. 2020

Rule #2: Death and Taxes

I remember my parents quipping throughout my childhood that there are only two sure things in this life, death and taxes. But while I can’t speak for their fiduciary responsibilities, rotifers have been able to generally cheat the former.

When an organism is deprived of water, it usually dies. Cells shrivel, biological processes shut down, and life ends.

When conditions turn hostile for rotifers, when droughts dry up their ponds, when ice encases them, when the world around them becomes unlivable, rotifers don’t really die. They shut down, entering a sort of paused or stalled state, called cryptobiosis. Their bodies lose nearly all water content, their metabolism grinds to a halt, and for all practical purposes, they are lifeless husks of a microorganism. But give them a single drop of water, and they wake up, pretty much just as they were before.

Some rotifers can survive in this suspended animation for decades. Others have gone far longer. In one of the most staggering discoveries, scientists revived a 24,000-year-old rotifer from Siberian permafrost, and it immediately resumed life, eating, cloning itself, and otherwise carrying on as if it had just taken a nap. I’m not too well-versed on Marvel films, but I’m 99% sure this was basically the plot of a Captain America movie.

Most creatures don’t get a second chance at life, and this individual superpower bodes well for the species as a whole. Limited though it may be, fossil evidence suggests they’ve been around for tens of millions of years, enduring planetary shifts, ice ages, and environmental catastrophes that wiped out far larger and more powerful creatures. I think it’s safe to say they’re well positioned for another few dozen million years, come what may.

image credit: Wiedehopf20

The Things We Think We Know

Rotifers challenge what I thought I knew about survival itself. They don’t evolve the way they should, they don’t die when they should, and they have little regard for the biological limits we assume all creatures must adhere to.

Despite their microscopic size, rotifers keep ecosystems running, breaking down organic material, cycling nutrients, and supporting food webs that stretch far beyond their little dominion.

Science is full of rules. They help us understand how the world works. But rotifers are proof that rules aren’t always as rigid as we think. They remind me that life’s possibilities are bigger, weirder, and more resilient than we might imagine.

Brendan Kelly began his career teaching conservation education programs at the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium. He is interested in how the intersection of informal education, mass communications and marketing can be retooled to drive relatable, accessible climate action. While he loves all ecosystems equally, he is admittedly partial to those in the alpine.

Dive Deeper

- Birky, C. William. 2004. “Bdelloid Rotifers Revisited.”

- Nicolas Debortoli. 2016. Genetic Exchange among Bdelloid Rotifers Is More Likely Due to Horizontal Gene Transfer Than to Meiotic Sex

- Gladyshev, Eugene A., Matthew Meselson, and Irina R. Arkhipova. 2008. “Massive Horizontal Gene Transfer in Bdelloid Rotifers.”

- Weisberger, Mindy. 2021. “24,000-year-old ‘zombies’ Revived and Cloned From Arctic Permafrost.”