What creature grows backwards and can swallow a tree whole?

The strangler fig!

A Fig Grows in Manhattan

I recently wrapped a fig tree for the winter. Nestled in the back of a community garden, in the heart of New York City, I was one of many who flocked not for its fruit but for its barren limbs. An Italian cultivar, and therefore unfit to withstand east coast winters, this fig depends on a bundle of insulation to survive the season. The tree grows in Elizabeth Street Garden, a space that serves the community in innumerable ways, including as a source of ecological awareness.

Wrapping the fig was no small task. With frozen fingers we tied twigs together with twine, like bows on presents. Strangers held branches for one another to fasten, and together we contained the fig’s unwieldy body into clusters. Neighbors exchanged introductions and experienced volunteers advised the novice, including me. Though I’d spent countless hours in the garden, this was my first fig wrapping. My arms trembled as the tree resisted each bind. Guiding the branches together without snapping them was a delicate balance. But caring for our fig felt good and I like to think that after several springs in the sunlight it understood our efforts. Eventually, we wrapped each cluster with burlap, stuffed them with straw and tied them off again. In the end, the tree resembled a different creature entirely.

Growing Down

Two springs earlier, I was wrapped up with another fig. I was in Australia for a semester, studying at the University of Melbourne, and had traveled with friends to the northeast coast of Queensland to see the Great Barrier Reef. It was there that I fell in love with the oldest tropical rainforest in the world, the Daintree Rainforest.

The fig I found there was monumental. Its roots spread across the forest floor like a junkyard of mangled metal beams that seemed to never end. They climbed and twisted their way around an older tree, reaching over the canopy where they encased it entirely.

Al Kordesch, iNaturalist, CC0

(Image by author).

The strangler fig begins its life at the top of the forest, often from a seed dropped by a bird into the notch of another tree. From there it absorbs an abundance of light inaccessible to the forest’s understory and sends its roots crawling down its support tree in search of fertile ground. Quickly then, the strangler fig grows, fueled by an unstoppable combination of sunlight, moisture, and nutrients from the soil. Sometimes, in this process, the fig consumes and strangles its support tree to death, hence its name. Other times, the fig can actually act as a brace or shield, protecting the support tree from storms and other damage. Even as they may overtake one tree, strangler figs also give new life to the forest.

As many as one million figs can come from a single tree. It is these figs that attract the animals who disperse both their seeds and the seeds of thousands of other plant species. With more than 750 species of Ficus feeding more than 1,200 distinct species of birds and mammals, the fig is a keystone resource of the tropical rainforest —the ecological community depends upon its presence and without it, the habitat’s biodiversity is at risk.

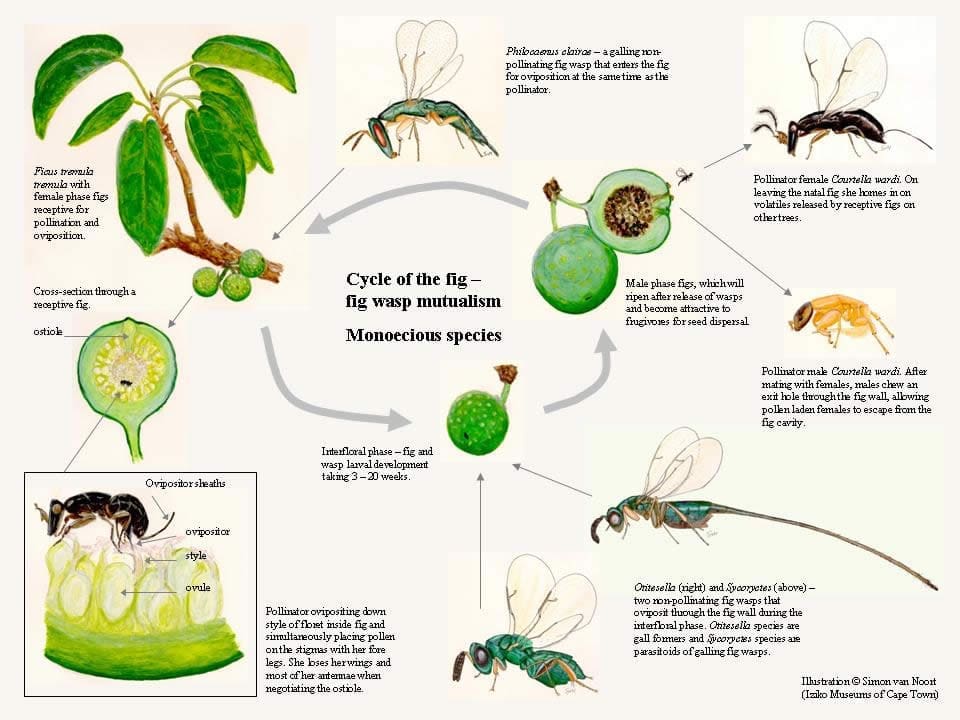

Fig-Wasp Pollination

Like the strangler fig, its pollination story is also one of sacrifice. Each fig species is uniquely pollinated by one, or in some cases a few, corresponding species of wasp. While figs are commonly thought of as fruit, they are technically capsules of many tiny flowers turned inward, also known as a syconium. This is where their pollination begins. The life of a female fig wasp essentially starts when she exits the fig from which she was born to reproduce inside of another. Each Ficus species depends upon one or two unique species of wasps, and she must find a fig of both the right species and perfect stage of development. Upon finding the perfect fig, the female wasp enters through a tiny hole at the top of the syconium, losing her wings and antennae in the process. She will not need them again, on a one way journey to lay her eggs and die. The male wasps make a similar sacrifice. The first to hatch, they are wingless, only intended to mate with the females and chew out an exit before dying. The females, loaded with eggs and pollen, emerge from the fig and continue the cycle.

(U.S. Forest Service, Illustration by Simon van Noort, Iziko Museum of Cape Town)

The mutualistic relationship between the fig and its wasp is critical to its role as a keystone resource. As each wasp must reproduce additional fig species in the forest at different stages of development, there remains a constant supply of figs for the rainforest.

However, climate change threatens these wasps and their figs. Studies have shown that in higher temperatures, fig wasps live shorter lives which makes it more difficult for them to travel the long distances needed to reach the trees they pollinate. One study found that the suboptimal temperatures even shifted the competitive balance to favor non-pollinating wasps rather than the typically dominant pollinators.

Another critical threat to figs across the globe is deforestation, in its destruction of habitat and exacerbation of climate change. In Australia, this threat looms large. Is it the only developed nation listed in a 2021 World Wildlife Fund study on deforestation hotspots, with Queensland as the epicenter of forest loss. Further, a study published earlier this year in Conservation Biology concluded that in failing to comply with environmental law, Australia has fallen short on international deforestation commitments. Fortunately, the strangler figs I fell in love with in the Daintree are protected as part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1988 and Indigenous Protected Area in 2013.

(Image by author)

(Image by author)

Stewards of the Rainforest

The Daintree Rainforest has been home to the Eastern Kuku Yalanji people for more than 50,000 years. Aboriginal Australians with a deep cultural and spiritual connection to the land, the Eastern Kuku Yalanji have been fighting to reclaim their ancestral territory since European colonization in the 18th century. Only in 2021 did the Australian government formally return more than 160,000 hectares to the land’s original custodians. The Queensland government and the Eastern Kuku Yalanji now jointly manage the Daintree, Ngalba Bulal, Kalkajaka, and Hope Islands parks with the intention for the Eastern Kuku Yalanji to eventually be the sole stewards.

Rooted in an understanding of the land as kin, the Eastern Kuku Yalanji people are collaborating with environmental charities like Rainforest Rescue and Climate Force to repair what’s been lost, reforesting hundreds of acres and creating a wildlife corridor between the Daintree Rainforest and the Great Barrier Reef. The corridor aims to regenerate a portion of the rainforest that was cleared in the 1950s for agriculture.

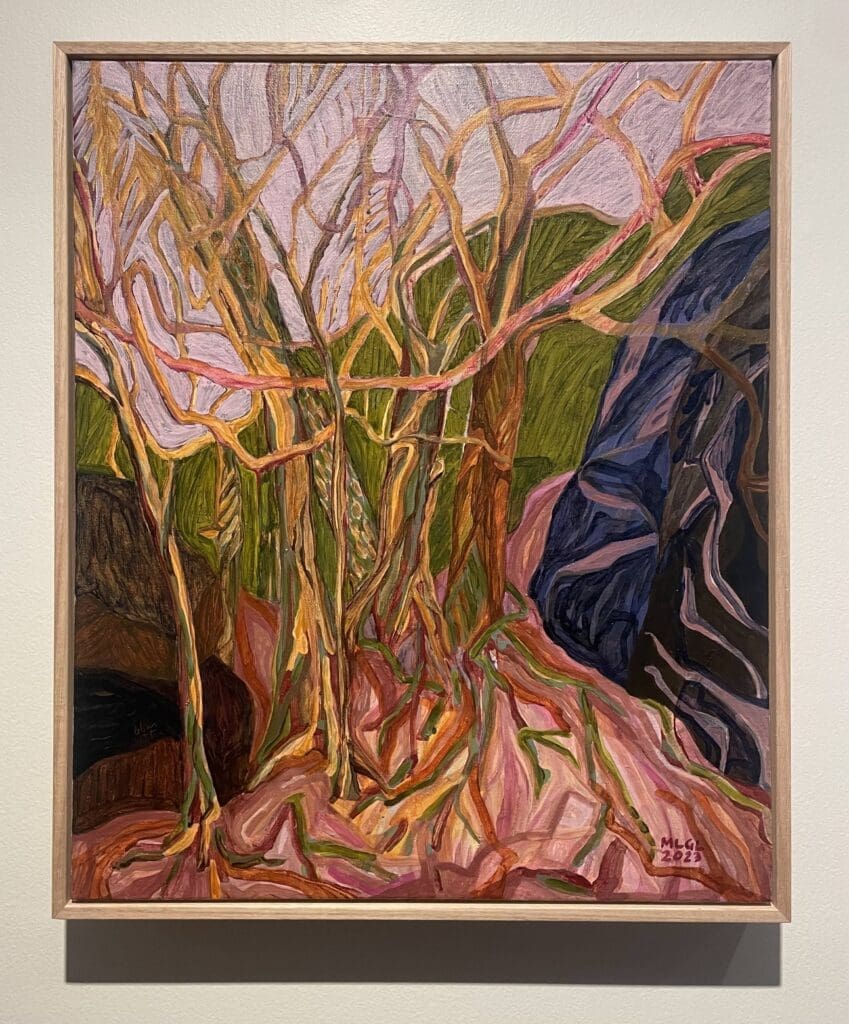

Upon returning to Cairns from the rainforest, we set sail and marveled at the Great Barrier Reef. My memories of the Daintree’s deep greens mingled with the underwater rainbow of the reef. At the Cairns Art Gallery the next day, a solo exhibition of artist Maharlina Gorospe-Lockie’s work, Once Was, visualized this amalgamation of colors in my mind. Gorospe-Lockie’s imagined tropical coastal landscapes draw from her work on coastal zone management in the Philippines and challenge viewers to consider the changes in our natural environment.

From the solo exhibition Once Was at the Cairns Art Gallery. (photo by author).

On the final day wrapping our fig in New York, I lean on a ladder above the canopy of our community garden and in the understory of the urban jungle. Visitors filter in and out, often stopping to ask what we’re up to. Some offer condolences for the garden and our beloved fig, at risk of eviction in February. We share stories of the burlap tree and look forward to the day we unwrap its branches.

The parallel lives of these figs cross paths only in my mind, and now yours. Perhaps also in the fig on your plate or the tree soon to be planted around the corner.

Jane Olsen is a writer committed to climate justice. Born and raised in New York City, she is driven to make cities more livable, green and just. She is also passionate about the power of storytelling to evoke change and build community. This fuels her love for writing, as does a desire to convey and inspire biophilia. Jane earned her BA in English with a Creative Writing concentration and a minor in Government and Legal Studies from Bowdoin College.

Sources and Further Reading:

- Gods, Wasps and Stranglers, Mike Shanahan, 2018

- Under the Banyan

- World Rainforests

- Smithsonian Gardens

- Catalyst: The Ingenious Strangler Fig

- NRDC

- Fig wasp, Norman F. Johnson, 2013

- USDA

- Changes in temperature alter competitive interactions and overall structure of fig wasp communities, Khin Me Me Aung, et al. 2022

- Higher temperatures make it difficult for fig tree pollinators, Uppsala University, 2022Figs and the Diversity of Tropical Rainforests, Rhett D Harrison, 2005

- Small populations of fig trees offer a keystone food resource and conservation benefits for declining insectivorous birds, K.D. Mackay et al. 2018