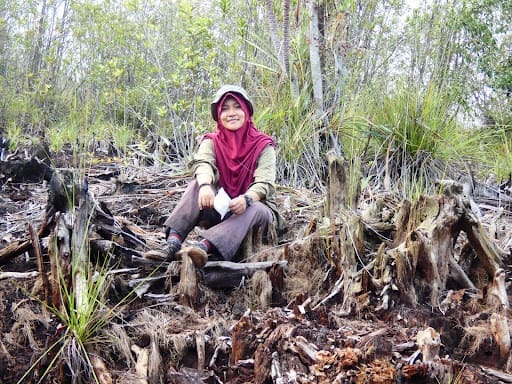

Meet Eka Cahyaningrum, restorer of peatlands and advocate for primates. Her work in Indonesia restores wild animal populations and their habitats while uplifting local communities. Her youth-led efforts demonstrate the power of coming together under one goal: to create better living conditions for all living beings, so that we can all thrive.

Eka Cahyaningrum, Primate Researcher and 2022 Global Landscapes Forum Restoration Steward

In higher education, my interest was in amphibians and reptiles, but before I graduated I got an internship to work with a primate researcher. I was going to the forest at 5am and arriving back home around 7pm. By staying the whole day in the forest following primates and observing their daily life, I couldn’t help but fall in love! I saw how each of them had their own personality and the resemblance of human behavior in their hierarchical societies. The first time I worked with macaques, then with orangutans, later with gibbons and langurs, and currently I’m working with gibbons and orangutans again.

My work expanded to peat ecosystems when I was working with gibbons and langurs in Central Borneo in 2017. I was observing them in the peat swamp forest, following their daily life and joining the conservation team to do restoration projects in an ex-burned area. Later on, in the dry season of 2019, I joined fire fighting as a way to see how I can contribute more to environmental movements. Since then, I started to learn more about this ecosystem and connect with peat researchers, and that’s when my interest in peatland restoration piqued. In 2021 I started my own restoration project with my friends and one year later I received the support of Global Landscapes Forum. Now I combine my passions for primates and peatlands, while acknowledging that none of these projects can be successful without the help of the local community.

Restoration is more than planting trees, but also about the community surrounding the peatland. To make sure the goal of restoration is achieved, we have to involve the community, raise their awareness and find the connection between nature and what they need. For example, we can emphasize the economic benefit of the peatlands and how they provide a reliable source of fish when they’re functioning ecosystems. If the community is prosperous, and the prosperity is caused by the sustainable management of the peatland ecosystem around them, then it will be a part of their culture to take care of the peat ecosystem.

For the ecosystem itself, since the majority of the degraded peatlands have damaged hydrological functions, the first thing we have to do is to restore the hydrological cycle by restoring the bed of water and the surrounding vegetation. Through these methods, the peat will regenerate, but it will take a really long time to fully recover.

Tropical forest and peatlands provide important ecological, climate and socio-economic benefits. Peatlands also deliver numerous important ecosystem services to local people, including maintaining air and water quality, providing timber and non-timber resources, and supporting fish populations for local consumption. As wetland ecosystems, peatlands prevent flood and drought, the biomass is useful as a carbon sink, and they provide habitat for a variety of plants and animals. This is all to say that peatlands are important for biodiversity, they provide a source of life for the people in the area, and they’re resilient in the face of rising climate-related disasters.

Our organization Hirai aims to raise awareness about environmental degradation, and the need for solutions that support local communities In Central Kalimantan, Indonesia.

With our different backgrounds and expertise we can tackle the problem with different approaches and can see it from different perspectives, so it is actually a very beneficial formation. We can tackle the problem through education, a business perspective, and from a scientific point of view.

For example, to understand more about the biophysical benefits of peat and to carry out research on how to restore peatlands, we can use a scientific approach. To increase awareness, we educate through social media and offline. And to support the communal livelihood dependent on fishing, we can find a suitable business model that incorporates restoration, such as through ecotourism or product development.

Tania Roa, Digital Communications and Outreach Manager for Bio4Climate

Eka Cahyaningrum’s story is one of love, dedication, and curiosity. Her love for other species led to her love for the habitats they call home, and that led to her love for the human communities that also call the peatlands home. It’s also a story of connection. Only by spending time in the forest, away from a cell phone signal and the convenience of the city, could Eka truly understand the threats gibbons and orangutans face. She was willing to step into their world, if only for a moment, and that makes all the difference for both people and primates. Finally, this is a story of youth leadership. Eka and her friends were unwilling to leave their futures and the rest of Indonesia’s in the hands of authorities. As the peatlands’ water levels dropped and the endemic fish in the rivers began to disappear, they didn’t hesitate or wait until someone else stepped in. They took it upon themselves to take action, not knowing where it would take them. Without the guarantee of success or financial support, this was a courageous choice founded upon their dedication to a greener and bluer archipelago.

These grassroots efforts are making a difference for Indonesia’s forests, biodiversity, wetlands, and citizens. When water cycles are nurtured, the abundance of seafood returns and people benefit. When forests are advocated for, storm buffers and healthy soils that support regenerative agricultural practices become widespread, and the community is better for it. Because of people like Eka, we can see the tangible results of localized, village-led restoration efforts.

We don’t have to be in Indonesia to support on-the-ground efforts like these. As Eka says, “collaborations are always welcome to spread our message and raise awareness on the importance of peat ecosystems.” As a small nonprofit, Hirai can use all the international support it can get. As global citizens, we can support one another’s restorative work regardless of where we’re based. When we work together, we accomplish so much more, and at a much faster pace. Peatlands sequester carbon and build biodiversity that then reverberates across the planet, so join me in supporting Eka’s efforts today.

Follow Eka’s journey through Global Landscapes Forum and follow Hirai on social media! And share Eka’s story to inspire others to preserve the Earth’s wetlands:

By Tania Roa and Eka Cahyaningrum