What a thrilling week it has been! Since last Thursday’s New York Times article Tiny Forests with Big Benefits, my teammates and I at Bio4Climate have been buzzing with excitement at the recognition our forests and this type of restoration is getting. We are so thrilled by the enthusiasm of people’s responses, from interest in implementing native plantings and eco-restoration projects in their own communities to an influx of questions and suggestions for our work in the Boston area.

Since so many people are new to us and to this work, I wanted to cover some of the basics of what we’re talking about with this ‘mini-forest revolution’, and why these plantings are much bigger than what meets the eye.

Why are Miyawaki forests important?

Well, like forests (and healthy ecosystems everywhere), Miyawaki forests provide biodiversity, habitat, clean air, clean water, cooling, shade, and beauty, and can bring these essential functions into built environments where nature has been degraded and excluded. Though we often talk about the importance of nature to birds, insects, and animals, trying to speak for creatures who can’t advocate for themselves, humans need nature too.

Flourishing green spaces are great for mental and physical health, create a place for connection and enjoyment, and buffer extremes in weather that can be so harmful to communities. And crucially, because Miyawaki forests can be created in small pockets of space (1000 sq ft or more), these plantings give us a way to fight environmental injustice and target heat islands in our urban areas in a practical and strategic way.

What belongs in a Miyawaki forest?

Native saplings appropriate to the potential natural vegetation of an area are what make up a Miyawaki forest. This includes trees and shrubs belonging to the different vertical layers of a forest canopy (after all, in nature no space is wasted). It also consists of a living forest floor teeming with fungal and microbial activity, jump started by soil remediation, that fosters an intricate underground network of life.

Early successional vegetation (or colloquially ‘weeds’) don’t belong. Neither do non-native trees. As a blanket statement, these types of vegetation aren’t awful or malicious, and may even have certain strengths. However, we work in the first few years of forest establishment to remove this competing ground cover, as it interferes with the slower growth of the trees we’ve planted.

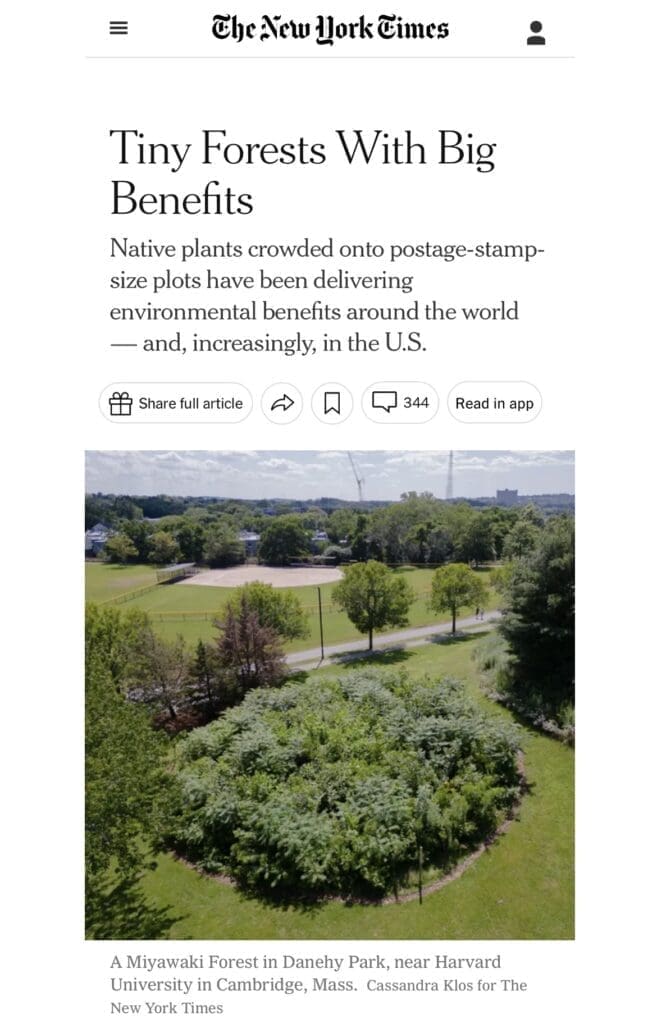

(Photo by Cassandra Klos)

How do we make sure a forest planting is successful?

Well, we start by following the Miyawaki Method, which is based on understanding the site of planting and the healthy forest communities that once flourished there. After a site survey, species survey, soil preparation, forest design, community planting, and two to three years of site maintenance, the forest becomes a self-sustaining ecosystem. But even after that, change within the forest is constant, as slower-growing canopy trees overtake companions that have shot up quickly, as individuals topple and create gaps for other saplings to fill, as new seeds dropped in by birds germinate, and the soil itself changes composition in response to these dynamics.

Like everything in nature, restoration, and the ecological succession that occurs in a Miyawaki forest, takes time. It’s a humbling process to participate in, to work to jumpstart an ecosystem, do what we can to steward it, and respect that the behaviors and interdependent activities in the system drive most of what happens afterward. We are learning as these years unfold what works best in adapting this method to our region. As we keep monitoring, maintaining, planting, and observing these pocket forests, we get to better understand how these processes unfold, and how we can play an appropriate role in this regeneration.

It is an honor and a joy to take part.

Thank you to everyone whose support makes this work possible! Your volunteering, donations, advocacy, and encouragement keep us going. Learn more about our Miyawaki Forest program and how you can participate.

Bonus: Should I plant a Miyawaki Forest?

It depends! Where do you live, and what is the natural ecosystem there?

The Miyawaki Method is an approach to reforesting previously forested areas, based on the natural vegetation there. While forests are wonderful, so are healthy grasslands, wetlands, and savannas. There are many different types of ecological restoration, and the process of regeneration begins with understanding your context – what ecological communities (including human communities) have existed there, what healthy functioning looks like, and what causes of degradation have led to the current state of things.

The exciting thing about community-led ecosystem restoration is that there are so many creative possibilities, and it all begins by connecting to what is around you and finding a place to contribute to the healing. Get started by learning more about ecosystem restoration in general, and finding out what is happening where you are.

Photos are by Cassandra Klos for The New York Times where stated, and otherwise by Maya Dutta, Danehy Park, 2023.

Hello!

I live in University City, MO, an inner ring suburb of the city of St. Louis. I am chair of our city’s Green Practices Commission, and we have been working on a tiny forest project. We have a lot of problem with local flooding from River Des Peres, which is a former river turned storm drainage canal. So we’re very interested in planting a Miyawaki forest as a pilot project, to see how it works in our city.

We’ve encountered some objections from our city forester and the city master garden planner. They both feel that even after the forest is established, there will be problems with invasives, notably bush honeysuckle, winter creeper, and anything that can be spread by bird droppings. They are concerned that this project will be more work for them down the line. I have seen bush honeysuckle grow in very shaded locations, and it does seem to pop up out of nowhere.

Have you had any experience with invasive plants continuing to grow in a Miyawaki forest after the 2-3 years it takes to stabilize it? Have you established a tiny forest that is self-sustainable after a few years?

Any advice you can give us would be appreciated. It seems like a project with so many benefits, I’d really like to see it work out.

Excellent blogpost, thank you!

NYT 4-pager on US groundwater depletion (9/2) omits mention of forest planting as a remedy. Bio4climate’s comprehensive info is valuable and needed!

Thank you Susan! You can find information on water and forests if you look for “biotic pump” and “small water cycles” on our site.