On October 4, Bio4Climate and the Miyawaki Forest Action Belmont (MFAB) community came together to plant a 3,000-square-foot Miyawaki Forest. In a single day, approximately 1,144 native trees and shrubs across 32 species were planted at a density of 4 plants per square meter. Around 275 local Belmont residents of all ages joined at some point throughout the day!

Initiated by community members, strengthened by student advocacy and school committee, and supported by Bio4Climate through our Associate Director of Regenerative Projects, Alexandra Ionescu, and our Ecology Advisor and botanist, Walter Kittredge, our eighth miniforest is especially inspiring—the MFAB community brought together a true intergenerational effort shaped by persevering collective action from early planning to planting day and beyond.

This project was made possible through the permission and support of the Belmont School Committee, whose approval enabled us to steward this land as a living classroom and community forest.

The drone shots taken by Dr. Nick Geron and Donovan Landry from Salem State University just before planting started beautifully capture what becomes possible when lawns and other open spaces in urban settings are reimagined to sustain all life, especially on school grounds — to participate in the water cycle, nutrient cycle, carbon cycle and to create habitat.

The impetus of this miniforest was to to create accessible green space and a living classroom that offers students and residents — present and future — new ways to connect with native plants and biodiversity.

Before this miniforest was planted, it began with the community members coming together to form the Miyawaki Forest Action Belmont (MFAB) group to imagine what it could become on the grounds of Belmont High School. Conversations unfolded with the school’s leadership, the Department of Public Works, and local groups. Plans were drawn, permits secured, sites considered, fundraising and outreach organized, and a team of dedicated community members came together over time.

The Bio4Climate team stayed largely in the background during these conversations, offering guidance as needed. We focused on the technical and ecological aspects of the miniforest—conducting the site assessment and Potential Natural Vegetation research, selecting species and finalizing the planting list, identifying necessary soil amendments, coordinating deliveries, supporting site preparation with the Belmont Department of Public Works, staging the plants, and supporting planting day.

In the midst of this work, when the weather got warmer, students gathered to visualize the forest’s shape and mark its outline on the ground. Class after class will walk past it for years to come, witnessing its growth — a true living classroom.

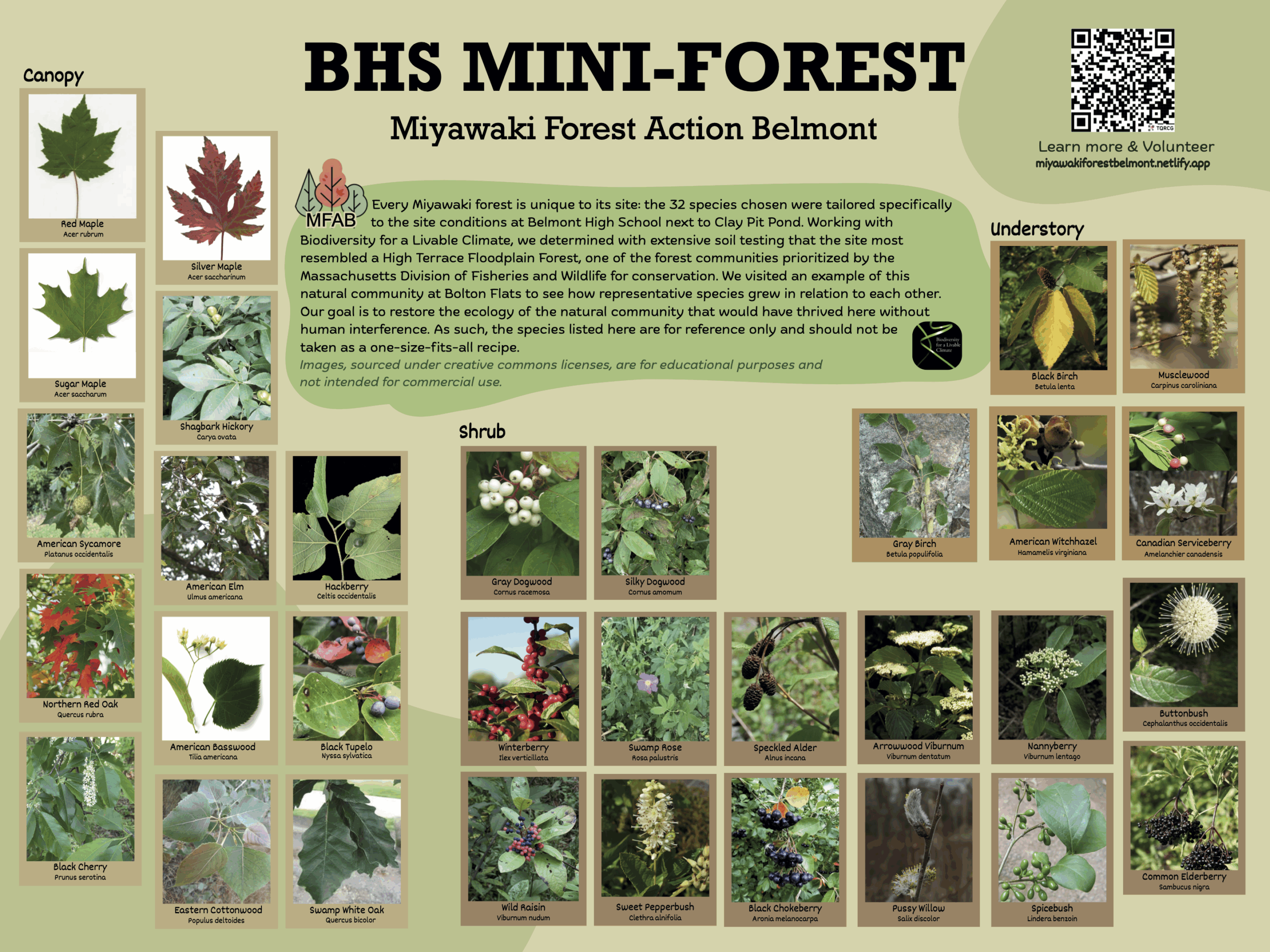

Site Assessment & Planting List Development

The site assessment began with a close look at the soil. Its proximity to Clay Pit Pond already offered clues about what lay beneath — confirmed when we found the clay layer just a foot below the surface. The soil type and infiltration rate revealed important insights into the kind of forest community that could thrive here.

We are grateful to botanist Walter Kittredge for joining this project and providing guidance at every stage of its development. Drawing on his extensive expertise, Walter identified a High Terrace Floodplain Forest as the most suitable native forest community for this site.

A High Terrace Floodplain Forest is a type of forest community that grows on slightly higher ground next to a river — land that doesn’t flood constantly but still stays moist from nearby water. The plants here are adapted to occasional flooding and wet soils, allowing their roots to tolerate being submerged for short periods without harm. Floodplain species, in general, have evolved remarkable adaptations to thrive in places where water levels rise and fall — a topic worthy of its own future Featured Creature post! Because clay particles are so fine, they pack tightly together and hold water for longer, meaning that after a heavy rain, it takes more time for water to soak into the ground.

If you’re in Massachusetts, you can explore the Classification of Natural Communities of Massachusetts fact sheets prepared by the NHESP (Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program). As part of our process, we studied the document on our particular forest community closely. Under the section on Public Access, they list precise locations where each forest community can be found. We chose the one closest to our site — at Bolton Flats Wildlife Management Area — reached out to the scientists to obtain the exact GPS coordinates, and then went to visit the site ourselves as part of the Potential Natural Vegetation research! We also spent time walking around the high school grounds, observing the existing vegetation as part of our site assessment where the process of planting list development started.

A large portion of the planting list is composed of climax canopy species. Early successional species—including black cherry (Prunus serotina), gray and black birches (Betula populifolia and Betula lenta), gray and silky dogwoods (Cornus racemosa and Cornus amomum), speckled alder (Alnus incana), as well as shrub species such as swamp rose (Rosa palustris), pussy willow (Salix discolor), and sweet pepperbush (Clethra alnifolia)—make up approximately 10% of the total planting, keeping the project within the threshold encouraged by the Miyawaki Method of 10% or less. We researched each species’ spreading strategy and placed rhizomatous species along the edge of the miniforest in smaller numbers, allowing their lateral growth to strengthen the forest boundary while leaving space for diversity to emerge.

Canopy species account for roughly 70% of the planting, with the remaining 30% evenly divided between the understory and shrub layers.

Several canopy species were available only in limited quantities, including basswood (Tilia americana), black tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica), and hackberry (Celtis occidentalis), while others—such as green and white ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica and Fraxinus americana)—could not be sourced at the time of planting due to nursery availability and impacts associated with the emerald ash borer. We also attempted to source butternut (Juglans cinerea) and bitternut hickory (Carya cordiformis), but these species were unavailable. Where necessary, ecologically appropriate substitutions were made to maintain floodplain function and structural diversity.

In addition to species characteristic of the High Terrace Floodplain Forest community, the final planting reflects species observed growing naturally near the site, as well as a small number of additional floodplain species.

One notable inclusion is speckled alder (Alnus incana), the only nitrogen-fixing species in the planting. Although an early successional species, it was distributed evenly throughout the site to support soil health and nutrient cycling.

The project supported four Massachusetts-based nurseries—one large and three small—helping to strengthen local native plant supply chains.

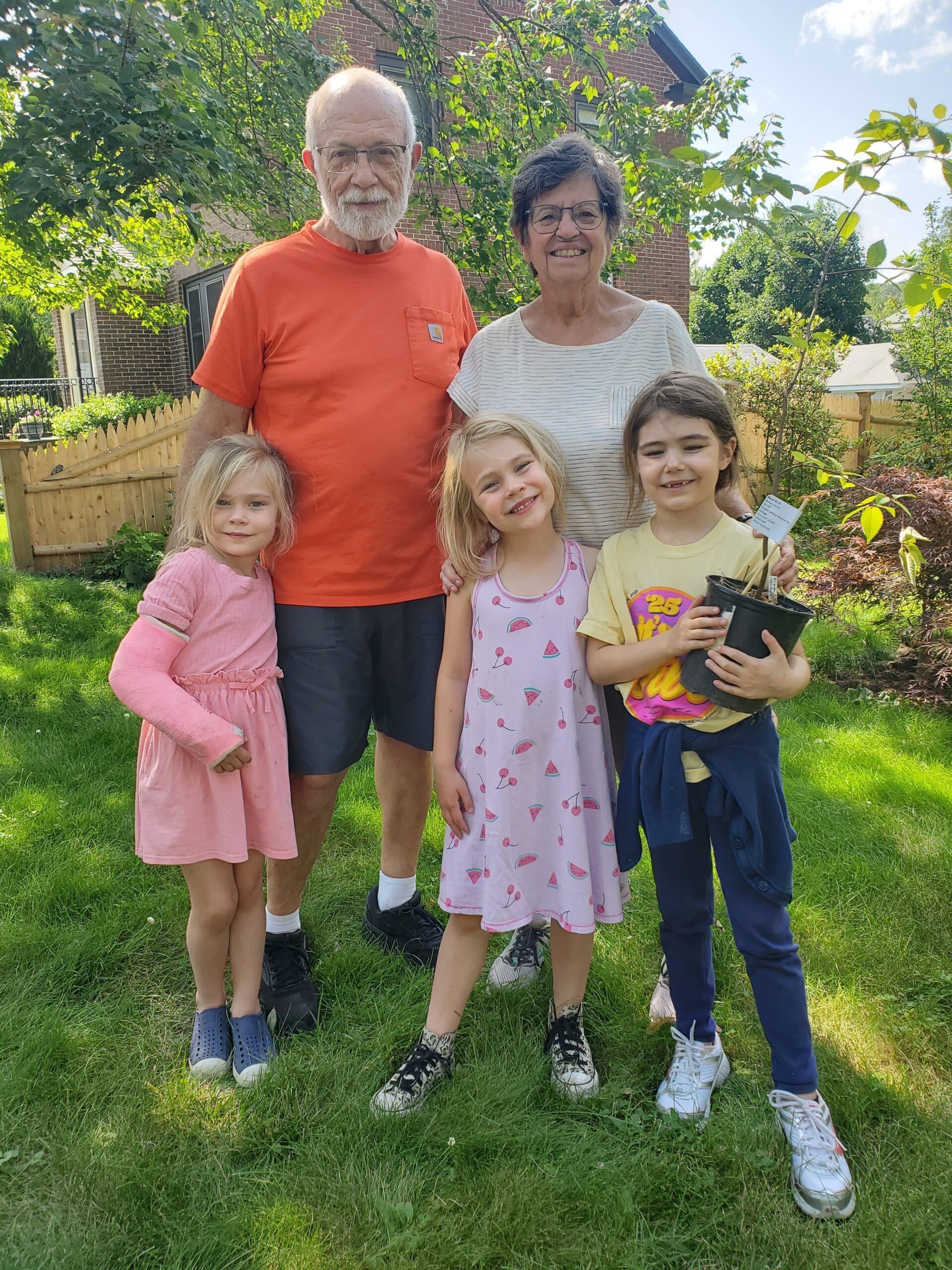

Foster-A-Tree Program

One of the highlights of this project for us at Bio4Climate was the Foster-A-Tree Program, initiated by Sarah Wang, a member of MFAB. Over the summer, the program distributed plants to community members to care for, which were then brought back and planted in the forest on planting day. And one of my most cherished memories from that day was helping a young boy find the shrub he and his family had taken care of and returned to the site — a beautiful example of how the program helped engage the community and deepen people’s connection to the miniforest, both before and beyond its planting.

In total, about 100 native plants were distributed by Sarah throughout the community. Below are just a few of the participants who cared for a plant over the summer before it was planted. Before giving the native plant to the residents, Sarah took a photograph to remember the moment.

Site Preparation

Erosion Control Installation

The first step in preparing the site was the installation of erosion control measures. Because the miniforest site lies within 100 feet of Clay Pit Pond, the project required review under the Massachusetts Wetlands Protection Act. Special thanks to Mary Trudeau of the Belmont Conservation Commission, whose guidance through the WPA Form 1 (Request for Determination of Applicability) process provided clear, actionable steps that allowed the project to move forward.

Additional thanks to Tayler Lendin and his team at Hartney Greymont for their support in installing straw wattles wrapped in biodegradable sleeves, completing the work despite rainy conditions.

Moving the Native Plant Garden

Another critical steps that preceded site preparation was the relocation of the BHS native plant garden that stood in the center of the grass island approved as the forest site.

This sunny garden, which contained over 30 species, had been planted in May 2023 and Oct. 2024 and maintained by the BHS Climate Action Club (CAC).

In early June, CAC liaisons Holly Kong and AJ Shaw guided students through site preparation for the future garden at the southern tip of the same grass island as the forest. They lay cardboard over a 600 sf triangle and covered that with a mix of topsoil and compost to smother the grass below.

Two months later, Holly, some CAC members, Sarah Wang, Jean Devine, and 13 of Jean’s Biodiversity Builders students dug, moved (by sled), and replanted clumps of native plants into this soil resulting in a beautiful new garden filled with native species that support pollinators, birds and wildlife. The garden offers opportunities for study and appreciation and complements the biodiversity of the forest.

Site Excavation and Soil Amendment Mixing with Belmont DPW

Once the erosion control installation and native plant garden relocation were complete, we began coordinating site excavation and soil amendment mixing with the Belmont Department of Public Works.

In August, with their incredible support, the site was excavated and the existing soil was mixed with a premium soil blend from Black Earth Compost and biochar from New England Biochar. We then mulched the site with a layer of leaf mulch, also from Black Earth Compost. Smelling and holding the leaf mulch signaled abundant biological activity, and a sense of vitality.

Cardboard Mulching for the Miniforest’s Collar

Following site preparation by the Belmont Department of Public Works, the MFAB team sourced cardboard and coordinated community volunteers and students to help lay cardboard and wood chips around the excavated site. This cardboard mulching process was used to suppress existing grass and prepare the area for future planting.

A collar of native plants will be established around the miniforest in phases, beginning in 2026. We extend our thanks to Tayler Lendin and his team at Hartney Greymont, who once again supported the project by donating wood chips.

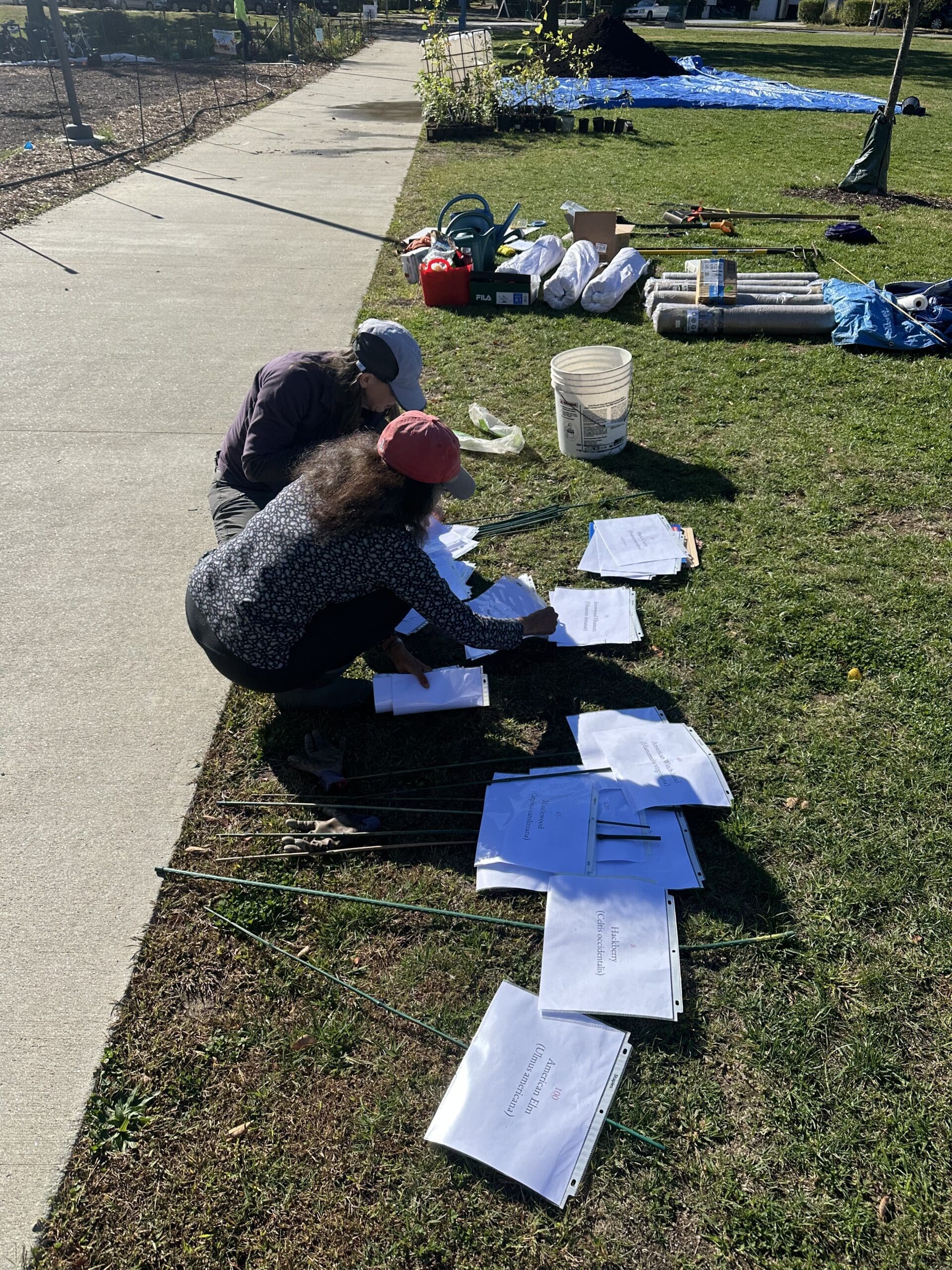

Pre-Planting Staging Day

One day before planting day, community members, Bio4Climate, and the MFAB group came together to receive plant deliveries and soil amendments, create and attach hand-written plant tags by MFAB team member Michelle Oishi, and map the site. The mapping process used chopsticks and a cardboard triangles—an efficient technique implemented by Sarah Wang that made it easy to lay out the site and accurately place the plants. We also pre-staged the plants, still relying largely on randomness, which helped planting day run more smoothly and efficiently. That said, with the added steps of tagging, site mapping, pre-staging, plant sorting, and other preparations, we realized we could have begun the process at least one day earlier.

Planting Day

Planting day was a joyful and vibrant community gathering, bringing together students, families, and neighbors of all ages in a hands-on act of hope. Laughter, learning, and teamwork filled the space as each sapling was placed in the ground, and with shovels in the soil and a shared sense of purpose, volunteers turned vision into reality—transforming the site into a symbol of collective action, intergenerational stewardship, and a stronger, more connected community.

At Bio4Climate, we are deeply impressed by Miyawaki Forest Action Belmont (MFAB)’s ability to truly mobilize an entire community. Their dedication and organization made it possible for hundreds of volunteers to contribute meaningfully, cultivating not only a thriving native forest but also a renewed sense of connection and shared responsibility. We hope these photos and videos convey the joy of planting day and provide a glimpse of the hope, energy, and community spirit that made the event so special.

by adding several oak trees.

Dr. Geron is pictured below.

It really does take a village—thank you all so much!

The community went above and beyond planting a miniforest. In addition to the Foster a Tree Program, they organized local plant sales, prepared sheet mulching for the collar surrounding the miniforest, sewed burlap along the fence to deter rabbits, coordinated the installation and operation of the irrigation system, and more.

Deep gratitude to all the volunteers who gave their time, care, and energy — from erosion control and cardboard installation to soil preparation and planting — and to all who will continue tending this young, emerging ecosystem.

Deep gratitude to the Belmont School Committee for their thoughtful support and approval, which made it possible to steward this site as a living classroom and community project. We also extend our thanks to Belmont Superintendent of Schools Jill Geiser and Belmont High School Principal Isaac Taylor.

Special thanks to Mary Trudeau of the Belmont Conservation Commission for guiding us through the preparation and submission of a Massachusetts Wetlands Protection Act (WPA) Form 1 (Request for Determination of Applicability) for permit review, required because the miniforest site lies within 100 feet of Clay Pit Pond.

A special thank-you to our Ecology Advisor, Walter Kittredge, who guided us through every step — from site assessment and potential natural vegetation research at Bolton Flats to developing the planting list.

Thank you as well to Andrew Putnam from the City of Cambridge, who advised us at different stages and generously shared compost tea on planting day.

Thank you to Tayler Lendin and his team at Hartney Greymont for support with the erosion control installation and wood chips donation.

We’re also grateful to local native nurseries — New England Wetland Plants, Oakhaven Sanctuary Nursery, Butterfly Effect Farm, and Russ Cohen — for growing these plants; to Black Earth Compost for transforming food waste into rich compost, leaf mulch, and living soil; to New England Biochar for contributing biochar that supports healthy soil systems; and to the Belmont Department of Public Works for their assistance with soil preparation.

And to the Miyawaki Forest Action Belmont (MFAB) leadership team for including us with our expertise in this initiative.

Lastly, we also extend our deep gratitude to the donors whose generosity and belief in this work supported the realization of this project.

Post-Planting Day, Monitoring & Future Care

After planting day, members of the MFAB Group have started the process of creating a map of the miniforest using the tags attached to each plant inspired by the process the Winchester miniforest used too. This map will help us track changes over time.

MFAB volunteers have continued to show their dedication and resilience this winter. When the call went out that the slatted snow fence needed reinforcement due to severe wind damage the week before Christmas, they came through with warm mittens and the right tools to reinforce snapped U-posts with much stronger T-posts which can withstand the force of prevailing winds that whip through the flat high school campus and across the forest on their way to Clay Pit Pond on the other side. The volunteers are hopeful the saplings will be as resilient to the frigid temperatures of their first winter. Thankfully, snow has been providing some insulation — as well as a way to monitor for animal tracks that reveal gaps in the fencing!

The group is also actively brainstorming next steps and will begin maintaining, monitoring, educating and caring for the miniforest with the support of students, Bio4Climate, and community members starting in Spring 2026. As mentioned above, the group is also planning the phased planting of native species in the miniforest collar, beginning in 2026.

To learn more about volunteer opportunities and stay connected with this miniforest, please visit MFAB’s website below:

For video collages and written articles by the local press, please see the links below:

- A video created by BHS students during Planting Day, featuring interviews and capturing the day’s energy

- Planting Day highlights, as covered by the Belmont Voice

- Garden Gems: Preparations Lead to Mini-Forest Planting Day Oct. 4

- Belmont’s First Miyawaki Forest Comes to BHS

- Belmont Prepares for ‘A Tiny but Mighty Forest’

- News Now: Belmont High Mini Forest Project – 07/22/25

This miniforest in Belmont is part of a growing regional and global movement to restore biodiverse forests in small urban and suburban spaces. In the Northeastern United States, practitioners, researchers, and community leaders gathered in July at the 2025 Northeast Miniforest Summit organized by Biodiversity For A Livable Climate to share experiences, strategies, and lessons from planting Miyawaki-inspired forests across cities, schools, and parks, reinforcing a network of people learning together how to make these living systems thrive.

Globally, the Miyawaki method has inspired thousands of pocket-forest projects—from community plantings in North America to initiatives in Europe and Asia—each adapting the core idea of dense native plantings to local ecologies and cultures.

As this miniforest establishes itself over time, it will continue to grow not only as an ecosystem, but as a shared practice of stewardship—inviting ongoing care, learning, and replication in other communities.

Join the conversation in the comments below! Tell us about your experience during planting day, your thoughts, or any questions you have.

All photos by Alexandra Ionescu (except where noted).