What animal, despite having the same number of vertebrae, has a neck longer than the average human, has spot patterns as unique between individuals as our fingerprints, and despite their gentle appearance, can kill lions with a karate-style kick!?

Image credit: Bird Explorers via iNaturalist (CC-BY-NC)

Some might say this is quite the… tall order for my very first Featured Creature profile! (Hold the applause!)

One of my earliest memories regarding these unique icons of the African savanna was when I was around five years old. My parents and I were visiting the Southwick Zoo in Mendon, Massachusetts, when we came upon the giraffe enclosure. One of these quiet, lanky creatures lowered its head across the fence bordering the enclosure, and licked my dad on the face with its looooong, black tongue! Once the laughter had died down, a flood of questions rushed into my head:

Why DOES the giraffe have such a long neck?

How do they sleep at night?

And what’s the deal with those black tongues?

A Tall-Walking, Awkwardly-Galloping African Animal

Their scattered range in sub-Saharan Africa extends from Chad in the north to South Africa in the south, and from Niger in the west to Somalia in the east. Within this range, giraffes typically live in savannahs and open woodlands, where their food sources include leaves, fruits, and flowers of woody plants. Giraffes primarily consume material of the acacia species, which they browse at heights most other ground-based herbivores can’t reach. Fully-grown giraffes stand at 14-19 feet (4.3-5.7 m) tall, with males taller than females. The average weight is 2,628 pounds (1,192 kg) for an adult male, while an adult female weighs on average 1,825 pounds (828 kg).

A giraffe’s front legs tend to be longer than the hind legs, and males have proportionally longer front legs than females. This trait gives them better support when swinging their necks during fights over females.

Giraffes have only two gaits: walking and galloping. When galloping, the hind legs move around the front legs before the latter move forward. The movements of the head and neck provide balance and control momentum while galloping. Despite their size, and their arguably cumbersome gallop, giraffes can reach a sprint speed of up to 37 miles per hour (60 km/h), and can sustain 31 miles per hour (50 km/h) for up to 1.2 miles (2 km).

When it’s not eating or galavanting across the savanna, a giraffe rests by lying with its body on top of its folded legs. When you’re 18 feet tall, some things are easier said than done. To lie down is something of a tedious balancing act. The giraffe first kneels on its front legs, then lowers the rest of its body. To get back up, it first gets on its front knees and positions its backside on top of its hind legs. Then, it pulls the backside upwards, and the front legs stand straight up again. At each stage, the individual swings its head for balance. To drink water from a low source such as a waterhole, a giraffe will either spread its front legs or bend its knees. Studies involving captive giraffes found they sleep intermittently up to 4.6 hours per day, and needing as little as 30 minutes a day in the wild. The studies also recorded that giraffes usually sleep lying down; however, “standing sleeps” have been recorded, particularly in older individuals.

Cameleopard

The term “cameleopard” is an archaic English portmanteau for the giraffe, which derives from “camel” and “leopard”, referring to its camel-like shape and leopard-like coloration. Giraffes are not closely related to either camels or leopards. Rather, they are just one of two members of the family Giraffidae, the other being the okapi. Giraffes are the tallest ruminants (cud-chewers) and are in the order Artiodactyla, or “even-toed ungulates”.

A giraffe’s coat contains cream or white-colored hair, covered in dark blotches or patches which can be brown, chestnut, orange, or nearly black. Scientists theorize the coat pattern serves as camouflage within the light and shade patterns of the savannah woodlands. And just like our fingerprints, every giraffe has a unique coat pattern!

The tongue is black and about 18 inches (45 cm) long, able to grasp foliage and delicately pick off leaves. Biologists thinks that the tongue’s coloration protects it against sunburn, given the large amount of time it spends in the fresh air, poking and prodding for something to eat. Acacia giraffes are known for having thorny branches, and the giraffe has a flexible, hairy upper lip to protect against the sharp prickles.

Both genders have prominent horn-like structures called ossicones, which can reach 5.3 inches (13.5 cm), and are used in male-to-male combat. These ossicones offer a reliable way to age and sex a giraffe: the ossicones of females and young are thin and display tufts of hair on top, whereas those of adult males tend to be bald and knobbed on top.

Image credit: Sienna Weinstein

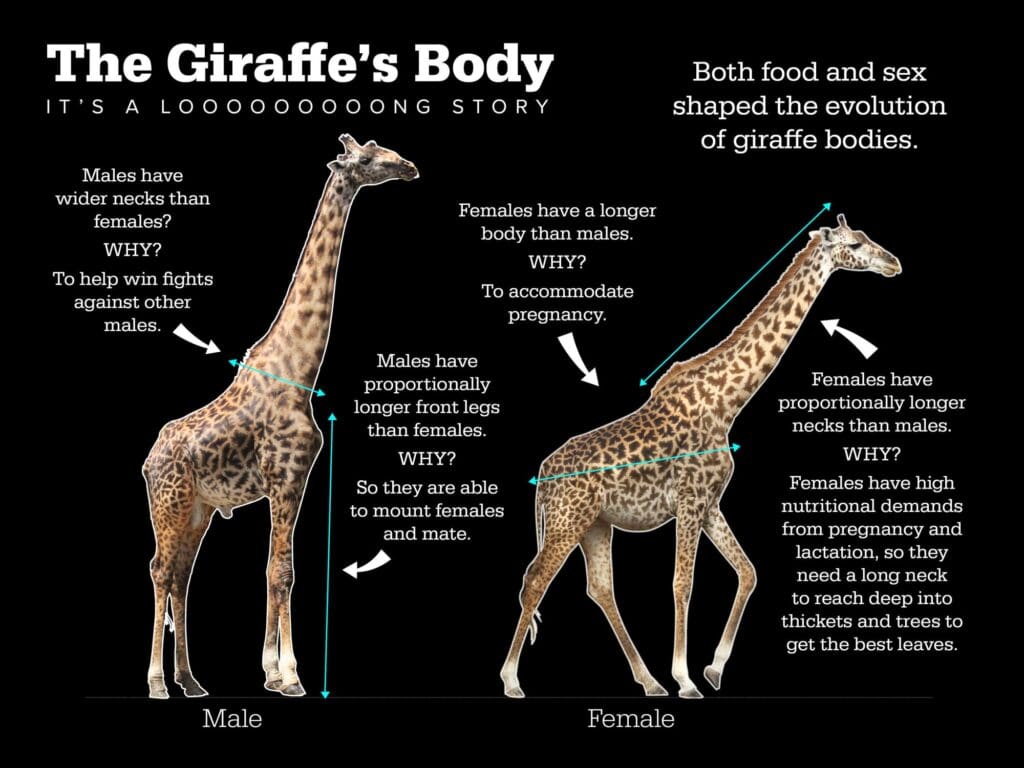

There is still some debate over just why the giraffe evolved such a long neck. The possible theories include the “necks-for-sex” hypothesis, in which evolution of long necks was driven by competition among males, who duke it out in “necking” battles over females, versus the high nutritional needs for (pregnant and lactating) females. A 2024 study by Pennsylvania State University found that both were essentially acceptable! Check out the graphic below for a good visualization.

Image credit: Penn State University, CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0

A Flagship AND Keystone Species

Alongside other noteworthy African savanna species, such as elephants and rhinoceroses, giraffes are considered a flagship species, well-known organisms that represent ecosystems, used to raise awareness and support for conservation, and helping to protect the habitats in which they’re found. As one of the many creatures that generate public interest and support for various conservation efforts in habitats around the world, giraffes have a significant role.

Giraffes, like elephants and rhinos, are also classified as a keystone species–one that plays a crucial role in maintaining the health and diversity of their native ecosystems, as their actions significantly impact the environment and other species. What is it that giraffes do that impacts their local ecosystems and environment? By browsing vegetation high up in the trees, they open up areas around the bases of trees to promote the growth of other plants, creating microhabitats for other species. In addition, through their dung and urine, they help distribute nutrients throughout their habitat. Some acacia seedlings don’t even sprout and grow until they’ve passed through a giraffe’s digestive system! By protecting giraffes, we also contribute to protecting other plant and animal species of the African savanna and open woodlands!

The Life We Share

The woodlands and grasslands where giraffes live are shaped in part by those long necks and unique feeding habits. As they browse high in the canopy, they open up space for other plants and animals to thrive. These ecosystems aren’t something we built, they’re something we’re lucky to witness. And if we have a role to play, maybe it’s simply to make sure our presence doesn’t undo the work that nature is already doing so well.

Sienna Weinstein is a wildlife photographer, zoologist, and lifelong advocate for the conservation of wildlife across the globe. She earned her B.S. in Zoology from the University of Vermont, followed by a M.S. degree in Environmental Studies with a concentration in Conservation Biology from Antioch University New England. While earning her Bachelor’s degree, Sienna participated in a study abroad program in South Africa and Eswatini (formerly Swaziland), taking part in fieldwork involving species abundance and diversity in the southern African ecosystem. She is also an official member of the Upsilon Tau chapter of the Beta Beta Beta National Biological Honor Society.

Deciding at the end of her academic career that she wanted to grow her natural creativity and hobby of photography into something more, Sienna dedicated herself to the field of wildlife conservation communication as a means to promote the conservation of wildlife. Her photography has been credited by organizations including The Nature Conservancy, Zoo New England, and the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. She was also an invited reviewer of an elephant ethology lesson plan for Picture Perfect STEM Lessons (May 2017) by NSTA Press. Along with writing for Bio4Climate, she is also a volunteer writer for the New England Primate Conservancy. In her free time, she enjoys playing video games, watching wildlife documentaries, photographing nature and wildlife, and posting her work on her LinkedIn profile. She hopes to create a more professional portfolio in the near future.