What animal swims upright and is one of the few where males carry the pregnancy?

The seahorse (Hippocampus)!

Image Credit: J. Martin Crossley via iNaturalist

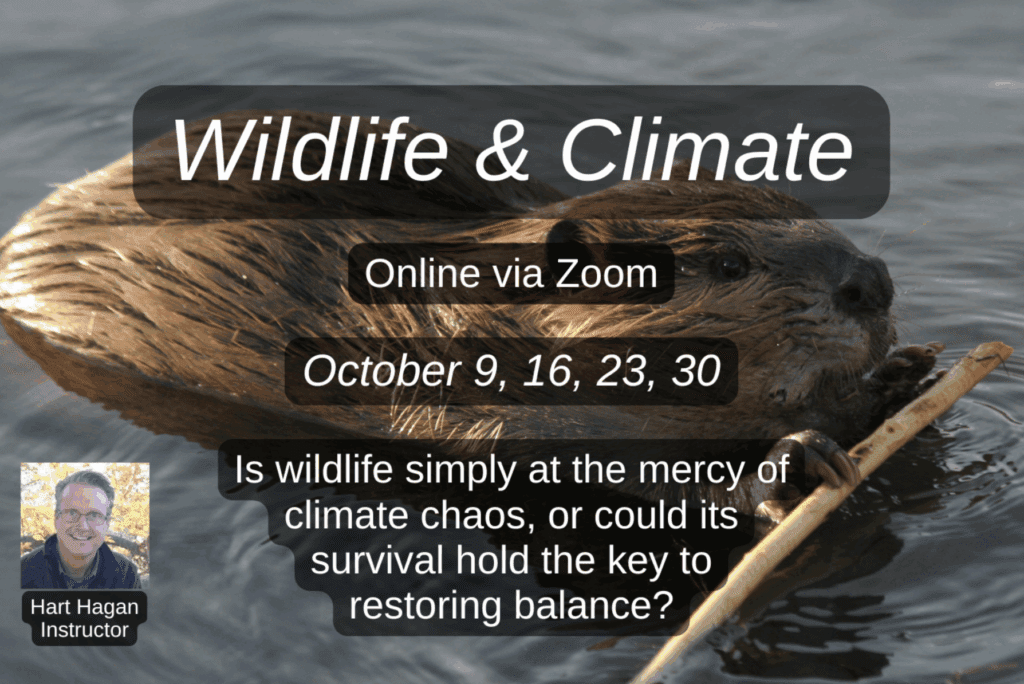

Introducing Our Spiny Friends

In celebration of my niece’s first birthday, my family and I visited the The New England Aquarium in Boston. As I watched her stare in awe through the glass, taking in all the colors and shapes of various plants and animals, I couldn’t help but tap into my own wonder. Together we brushed the smooth backs of Cownose rays, took in the loud calls of the African penguins, and spent quite a bit of time trying to find the seahorses in their habitats. Eventually we did find them, at the bottom, with their tails curled around bits of seagrass. Now, I already knew a couple details about seahorses: that they were named that way because of their equine appearance, and that they swam vertically. But, crouching there next to my niece, who was looking at them in such curiosity (and confusion), I began to feel…the same way. Why do they curl their tails around plants? Are they tired? How exactly do they eat if they don’t swim around? So when I got home that day I did what any curious person in the 21st century would do, I took to the internet and started learning more about them.

The Small Horses of the Sea

With a long-snouted head and a flexible, well-defined neck reminiscent of that of a horse, the seahorse is aptly named. Its scientific name, Hippocampus, comes from Ancient Greek: hippos, meaning “horse,” and kampos, meaning “sea monster.” In fact, the hippocampus in our brains is named that way because its shape resembles the seahorse.

These creatures can be as small as the nail on your thumb or up to more than a foot long. Out of all 46 species, the smallest seahorse in the world is Satomi’s pygmy seahorse, Hippocampus satomiae. Found in Southeast Asia, it grows to be just over half an inch long. The world’s largest is the Big-belly seahorse, Hippocampus abdominalis, which can reach 35 centimeters long (more than a foot), and is found in the waters off South Australia and New Zealand.

(Image Credit: Paul Sorensen via iNaturalist (CC-BY-NC))

Instead of scales like other fish, seahorses have skin stretched over an exoskeleton of bony plates, arranged in rings throughout their bodies. Each species has a crown-like structure on top of its head called a coronet, which acts like a unique identifier, similar to how humans can be distinguished from each other by their fingerprints.

A well-known characteristic of seahorses is that they swim upright. Since they don’t have a caudal (tail) fin, they are particularly poor swimmers, only able to propel themselves with the dorsal fin on their back, and steer with the pectoral fins on either side of their head behind their eyes. Would you have guessed that the slowest moving fish in the world is a seahorse? The dwarf seahorse, Hippocampus zosterae, which grows to an average of 2 to 2.5 centimeters (0.8-1 in.) has a top speed of about 1.5 meters (5 ft.) per hour. Due to their poor swimming capability, seahorses are more likely to be found resting with their tails wound around something stationary like coral, or linking themselves to floating vegetation or (sadly) marine debris to travel long distances. Seahorses are the only type of fish that have these prehensile tails, ones that can grasp or wrap around things.

How Do Seahorses Eat? By Suction!

Most seahorse species live in the shallow, temperate and tropical waters of seaweed or seagrass beds, mangroves, coral reefs, and estuaries around the world. They are important predators of bottom-dwelling organisms like small crustaceans, tiny fish, and copepods, and they have a particularly excellent strategy to catch and eat prey. As less-than-stellar swimmers, seahorses rely on stealth and camouflage. The shape of their heads helps them move through the water almost silently, which allows them to get really close to their prey.

(Jack McKee via iNaturalist

Can you find the seahorse in the picture above? As one of the many creatures that have chromatophores, pigment-containing cells that allow them to change color, seahorses mimic the patterns of their surroundings and ambush tiny organisms that come within striking range. They do what’s called pivot-feeding, rotating their trumpet-like snouts at high speed and sucking in their prey. With a predatory kill rate of 90%, I’d say this strategy works. Check out this video below to watch seahorses in action!

Mr. Mom

One of the most interesting characteristics of seahorses is that they flip the script of nature: males are the ones who get pregnant and give birth instead of the females! Before mating, seahorses form pair bonds, swimming alongside each other holding tails, wheeling around in unison, and changing color. They dance with each other for several minutes daily to confirm their partner is alive and well, to reinforce their bond, and to synchronize their reproductive states. When it’s time, the seahorses drift upward snout to snout and mate in the middle of the water, where the female deposits her eggs in the male’s brood pouch.

After carrying them for anywhere between 14-45 days (depending on the species) the eggs hatch in the pouch where the salinity of water is regulated, preparing newborns for life in the sea. Once they’re fully developed (but very small) the male seahorse gives birth to an average of 100-1,000 babies, releasing them into the water to fend for themselves. While the survival rate of seahorse fry is fairly high in comparison to other fish because they’re protected during gestation, less than 0.5% of infants survive to adulthood, explaining the extremely large brood.

(Image Credit: David Harasti via iNaturalist (CC-BY-NC))

A Flagship Species

Alongside sea turtles, seahorses are considered a flagship species: well-known organisms that represent ecosystems, used to raise awareness and support for conservation and helping to protect the habitats they’re found in. As one of the many creatures that generate public interest and support for various conservation efforts in habitats around the world, seahorses have a significant role.

Not only do these creatures act as a symbol for marine conservation, but seahorses also provide us with a unique chance to learn more about reproductive ecology. They are important predators of small crustaceans, tiny fish, and copepods while being crucial prey for invertebrates, fish, sea turtles, seabirds, and marine mammals.

How Are Seahorses Threatened?

Climate change and pollution are deteriorating coral reefs and seagrass beds and reducing seahorse habitats, but the biggest threat to seahorses is human activities. Overfishing and habitat destruction has reduced seahorse populations significantly. Bycatch in many areas has high cumulative effects on seahorses, with an estimated 37 million creatures being removed annually over 21 countries. Bottom trawling, fisheries, and illegal wildlife trade are all threats to seahorse populations. The removal of seahorses from their habitat alters the food web and disrupts the entire ecosystem, but seahorses are still dried and sold to tourists as street food or keepsakes, or even for pseudo-medicinal purposes in China, Japan, and Korea. They are also illegally caught for the pet trade and home aquariums (even though they fare poorly in captivity, often dying quickly).

Supporting environmentally responsible fishers and marine protected areas is a great way to start advocating for the ocean and its creatures. Avoiding non-sustainably caught seafood and avoiding purchasing seahorses or products made from them are ways to protect them too.

Project Seahorse, a marine conservation organization, is working to control illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing and wildlife trade for sustainability and legality, end bottom trawling and harmful subsidies, and expand protected areas. The organization also consistently urges the implementation and fulfillment of laws and promises to advance conservation for our global ocean.

The Life We Share

All creatures on this Earth rely on us to make sure the ecosystems they call home are healthy and protected. The ocean is not just an empty expanse of featureless water, but a highly configured biome rich in plants and animals, many of them at risk. So the next time you go to the aquarium and see those little seahorses with their tails wrapped around a piece of grass, remember that we are all part of the same world. Just as these creatures rely on us, we rely on them too.

Abigail

Abigail Gipson is an environmental advocate with a bachelor’s degree in humanitarian studies from Fordham University. Working to protect the natural world and its inhabitants, Abigail is specifically interested in environmental protection, ecosystem-based adaptation, and the intersection of climate change with human rights and animal welfare. She loves autumn, reading, and gardening.

Sources and Further Reading: