I’ve loved Chicago from the first day I set foot there, and I’ve missed the Windy City since I left after college in 2018. When I had a chance to visit two weeks ago, I made it a point to try to understand Chicago’s ecosystems better, and check in on the many ways communities across the city are building ecological resilience and spearheading stewardship.

From the water birds and prairie meadows along Lake Michigan to the small plots of mini-forest and urban garden embedded in a concrete jungle, I was thrilled and inspired to see the many examples of nature reviving and rewilding greater Chicago.

In these relatively modest sized areas, a transformation is underway… to bring people’s hands and hearts back to the soil.

Read on to see some of the sites I visited and learned from:

Markham Miyawaki Forest

The Markham Courthouse Miyawaki Forest was created in May of 2022 by Nordson Green Earth with the Markham municipality (a township slightly south of Chicago). Planted not long after our own Danehy Park Miyawaki Forest, this sister site is Illinois’s first Miyawaki Forest, and has been growing steadily since. Christine Dannhausen-Brun, who works on forest care, further plantings, and community engagement and education, gave me a tour of the forest and shared her insights on the project’s progress.

Photos by Christine Dannhausen-Brun

Christine and I met in 2022 when we both joined SUGi’s Fellowship for Miyawaki Forest makers. As the two American participants, we immediately connected over shared experiences with urban forestry in major US cities – with the desire to promote environmental justice and public health, the increasing investment in natural infrastructure and urban forestry, and the unique regulatory and bureaucratic processes that affect the adoption of mini-forest projects in this country.

As she guided me around the Markham courthouse mini-forest and described the developing prospects for two upcoming plantings in the community, we reconnected on these topics and shared what we have learned in the past two years of planting and stewarding.

Like with our forests in the Boston area, the Markham mini-forest is in its dormant state in late February, but with the weather fluctuations including some extremely warm days, I could spot some early budding and leaf out. Watching the husks of milkweed and echinacea cones, I could imagine the site teeming with insects and birds in summer months.

I can’t wait to see how the mini-forest grows, and how community members continue to steward and grow with the project.

The Wild Mile – Chicago River Restoration

I get really excited about slow water these days. It’s hard not to once you learn about the small water cycle and the great amount of agency we have in our relationship with water, to notice the many ways that our cities have been hardened and shelled over and eroded, no longer sponges but giant systems of gutters for water.

We got some torrential rain during the week I was in Chicago, as temperatures jumped between 70 and 30 degrees Fahrenheit, wind and hail and deluges of water taking the stage at various points. I noticed that the flooding along street corners is almost immediate, with drainage stalling for hours. As we’re seeing in so many areas around the country and the world as flood/drought cycles intensify, the infrastructure developed over the past century is being tested beyond capacity. That’s why I was so pleased to visit the Wild Mile, the world’s first floating eco-park developed along the Chicago River by Urban Rivers.

The Wild Mile, as suggested by the name, is planned to be a mile-long stretch of river restoration. The first section is now completed and open to the public 24/7, and I was thrilled to visit and see some of the waterway restoration principles I have learned about applied in practice. The reconstructed wetlands, floating beds of aquatic plants and native grasses, and boardwalk area for public access can support biodiversity, water filtration, stormwater buffering, ecological education, and climate resilience at larger and larger scales as cities embrace this blue-green infrastructure.

Part of what was astounding about this little park was the contrast to what the Chicago River looks like in most other places. I walked over to the Wild Mile from the 66 bus, which dropped me at the highway-like intersection of Chicago and Halsted. I hugged the river on the way over and saw how it is treated for most of its span – hemmed back by large steel brackets, stripped of embankment, with no public access, devoid of life – human or otherwise. In small patches, 30ft here and there, you might see stark, eroded, litter strewn soil, trees and brambles still growing, life still life-ing, but clearly without any sort of intention from people, except perhaps to overlook as quickly as possible. Trees still grow in small cracks, in the divots in the steel brackets over the river’s edge, cut back into stumps but still producing shoots. Life persists, but clearly it is beleaguered and unwanted.

The Wild Mile takes what has essentially become an industrial canal and opens it back up into a river. This is a system, where floating beds house grasses, wildflowers, and small trees, where freshwater mussels live and grow, filtering water as they go, where birds nest and hunt and court each other. It’s alive, and it felt like a sigh of relief. It felt like a livable future. It felt like resilience in action – this will flood, this will change, and it will remain because it can change. This space will bend and adapt, not break, and it will nurture life to help keep the balance.

The birds in the area were remarkable, a brilliant tapestry of geese, gulls, ducks, starlings, and cormorants. I’ve always wanted to see a murmuration of starlings, and I was blown away by their dance-like flight. Together with the gull and goose calls, the starlings’ fluid movements made for a symphonic experience. (Having visited the Art Institute and spent time with the masterpieces there, I found this no less mesmerizing.)

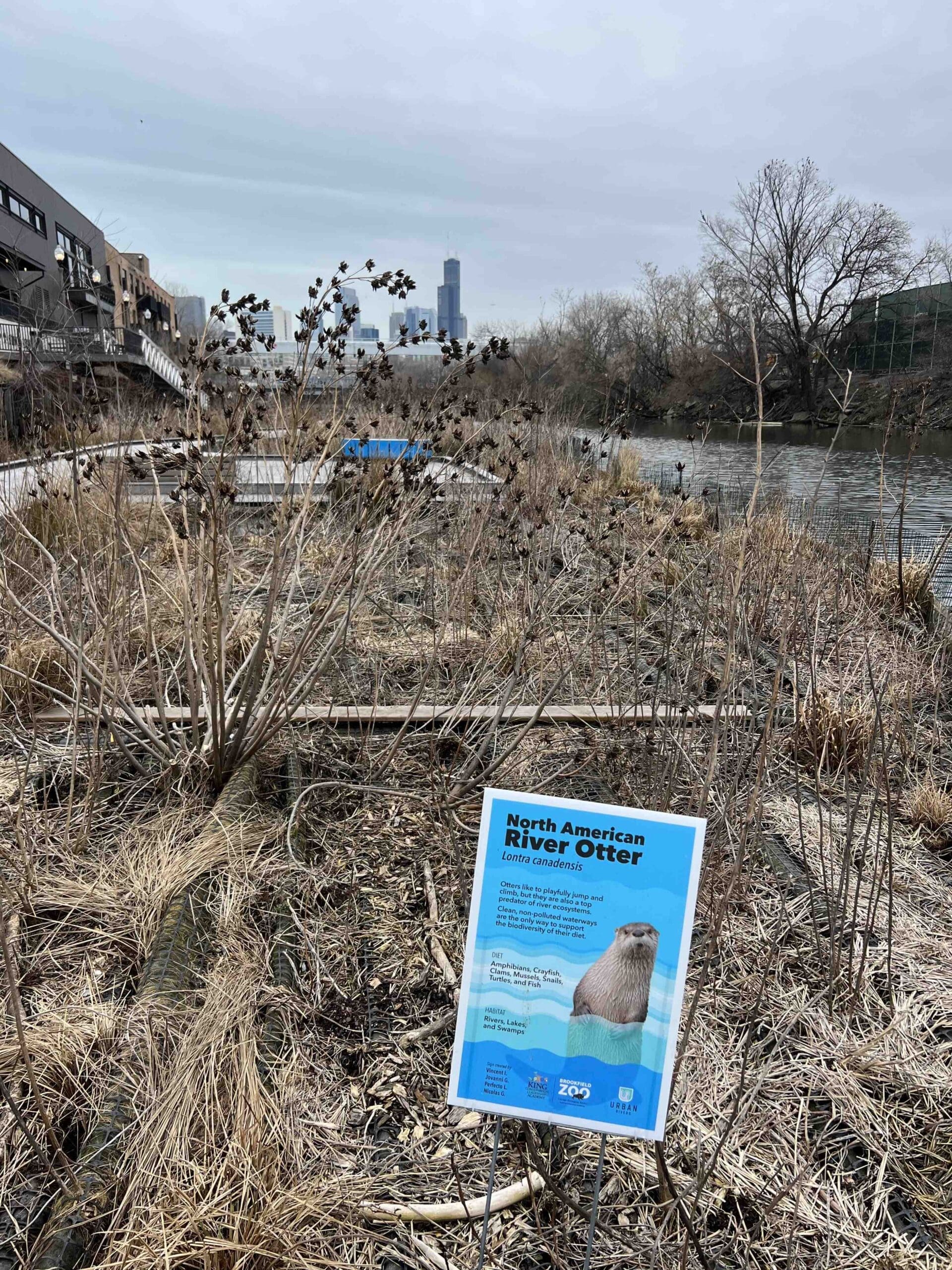

Beyond the birds, I spotted mussels, milkweed, native grasses, trees, and fungi bracketing fallen logs. I appreciated the signage introducing the public to some of the animals that visited or resided in the habitat – common snapping turtles, little brown bats, big brown bats (not closely related, it turns out), Eastern screech owls, and North American river otters. For an area of about 500 ft, this was obviously impacting hundreds of beings, at least. As it grows, its positive impacts will continue to ripple through Chicago and other cities that are willing to take this step into the future with regeneration and rewilding.

May it reach a mile soon, and many more beyond that.

Community Gardens and Native Plant Gardens

Finally, one of the most encouraging highlights from my trip were the many neighborhood gardens brought to life by a focus on pollinator friendly-plants or community food growing. As I walked around Humboldt Park, I passed a fairly small, wild-looking yard that made me stop and take notice. Bracketed by branches and a thick layer of leaves and straw, this looked like a haven for overwintering insects and the species that rely on them. When I looked more closely, I noticed the signs indicating just how intentional this stewardship was. “Your yard is nature,” said one, while the other read “Thank you for your smile.”

Further along, I encountered El Yunque Community Garden, where community members can come to learn, grow, and connect. Out of a couple dozen raised beds, some are set aside for garden members to plant, nurture, and pick, and several others line the street for public harvesting. At Thomas Street Community Garden, a sign similarly encouraged all community members to join and to learn. In these relatively modest sized areas, a transformation is underway, to bring fresh produce into people’s homes, and to bring people’s hands and hearts back to the soil. I was struck by how simply and gently restoration could take hold, from a few street corners and networks of neighbors to a sweeping change in attitudes about what a city can be and how people can relate to their ecology.

Across all of these projects, I once again appreciated that resounding lesson – that to take positive climate action, you can start small, wherever you are. That ecosystems are everywhere, and stewardship can look like many things. That taking care of your neighbors is taking care of yourself. That our world may be breaking or burning, but it is also living, still. And the more we nurture, the more we heal, the healthier, stronger, and more alive this whole Earth is.

Banner Photo by Christine Dannhausen-Brun. All other photos are by Maya Dutta, except where noted.

Dear Maya

Your beautiful descriptions and accurate pictures of an urban water wasteland’s restoration to Nature gives me hope and shows us all the way.

Thank you!

Now, to teach people to include more trees, feeding the soil biome and cooling the planet, and we can really build regenerative eco-restoration and climate stability. We can do it!

You’re spreading the word and making it real.

Thank you,

Sue

Beautifully quotable inspiration from Maya Dutta, “That our world may be breaking or burning, but it is also living, still. And the more we nurture, the more we heal, the healthier, stronger, and more alive this whole Earth is.”

Thank you Maya for this a beautiful piece, and for reminding me that “to take positive climate action, you can start small, wherever you are”.

I love what you write, and forward it to all my friends. Keep going!

Thanks Ranganath!! I really appreciate it.

Great writing, very readable! Love the river work; it’s a natural, over-looked corridor for species of many kinds

Thank you for this tour! I’ll be visiting Chicago in October and will certainly look to walk the Wild Mile.

Thanks Dianne! I think you can get an official tour from Urban Rivers staff or volunteers if you go (and plan a bit better than I did). Let us know how it goes 🙂