Four forestry specialists offer their views on how to reduce the wildfire risks.

The Wildfire story that no one is talking about. The media is full of stories about the causes and cures for the massive forest fires raging around the world. Those fires have finally hit close to the Bio4Climate home in New England as the smoke from Canadian fires turned our skies a hazy, dirty yellow color. As always, our scientists acknowledge the climate is hotter and drier and part of that has to do with carbon emissions. But could something else be making these forests more vulnerable? When we “listen to the land” what do we learn? Joan Baxter asked some of the same questions and shares what some forestry experts in Canada are saying. We share this very insightful reporting in its original format with permission from the Halifax Examiner. Comments are welcome at staff@bio4climate.org.

– Beck Mordini, Executive Director

Before we even start talking about forests and the recent wildfires, Wade Prest wants to tell me a story about Nova Scotia’s forests of yore.

Prest is a woodlot owner, professional forester and former president of the Nova Scotia Woodlot Owners and Operators Association, whose family settled in Mooseland in the 1870s.

That area – north of what is today the Tangier Grand Lake Wilderness Area and about 90 kilometres east of Stanfield International Airport – was the site of the colonists’ 1858 discovery of gold in what is now Nova Scotia. (Of course they didn’t find gold on their own, but were led to the area by a Mi’kmaq hunting guide.)

Mooseland is about 90 km east of Halifax’s Stanfield International Airport, in Halifax Regional Municipality, and just a few km from St. Barbara’s open pit gold mine at Moose River. Credit: Joan Baxter

Prest tells me that following the reports of gold in Mooseland, the British colonial governor of Nova Scotia sent provincial secretary Joseph Howe to the area to investigate. In 1860, Howe and his entourage hiked through the woods from the head of the Ship Harbour Great Lake to the discovery site.

This is what Howe wrote to the governor about the forests he saw on that trek:

The path was pretty well blazed all the way and was not so difficult as I had anticipated. It lay chiefly through hardwood hills and where there were bogs or swamps they were firm enough to traverse them with comparative ease. For nearly the whole distance we were shaded by the branches of an unbroken forest to which the attention of our merchants and enterprising capitalists ought to be turned. Noble groves of birch, beech, maple, hemlock and spruce interspersed with ash, oak and pine seemed to invite the axe of the lumberman. We could not but marvel how vague rumours of gold digging had so soon excited the population whilst so much real wealth, with lakes and streams offering great facilities for transit to the seaboard had been so long disregarded…

Prest says that within 25 years of Howe’s visit to the area, the land had all been granted to lumbermen.

“Over time, these grants were consolidated into ever-larger holdings,” Prest adds. Eventually, they were acquired by Hollingsworth and Whitney, a company based in Boston, which logged the area heavily in the 1930s.

For a time, Hollingsworth and Whitney was the largest private landowner in Nova Scotia. Then in 1955, the Boston company sold its holdings to Scott Paper of Philadelphia, which would build the Pictou pulp mill a decade later.

According to Prest, Scott logged the area heavily again in the 1980s. Now, he says, most of it belongs to yet another U.S. company, the investment firm Wagner Forest Management, and harvesting continues.

“But as far as Acadian forest goes, you won’t find anything there today,” Prest says. “A sad story.”

Forest change and climate change

That “sad story” is just the prelude to the interview Prest has agreed to do about the forests of Nova Scotia and the recent forest fires, and what might explain their rapid spread and intensity, whether it relates to the way we’ve managed our forests, or to something else.

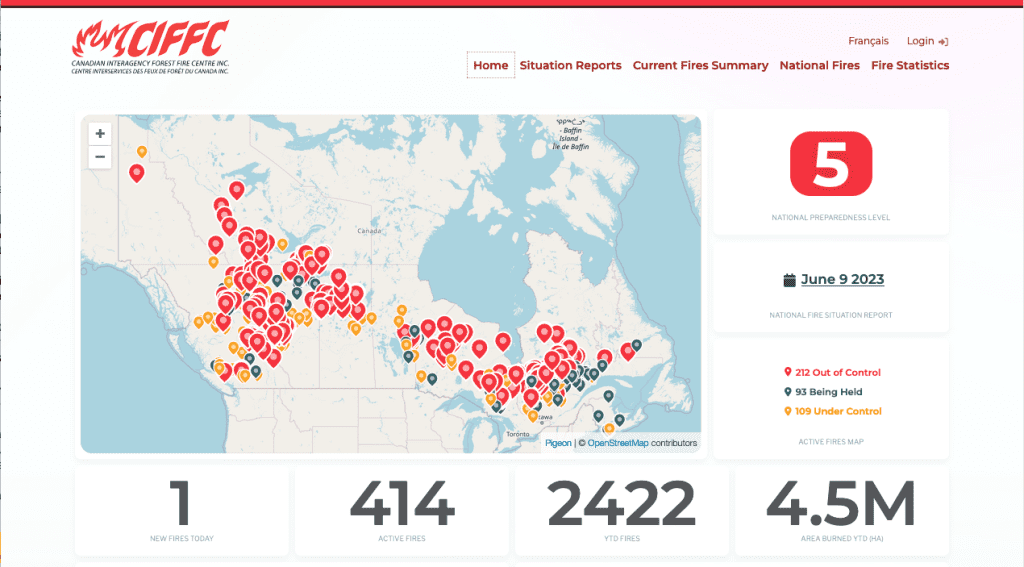

According to the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre, so far this year nearly 4.5 million hectares of forest have burned in Canada, an area the size of mainland Nova Scotia.

We are only in the second month of country’s annual six-month forest fire season. There are still hundreds of active wildfires across Canada causing evacuations, and air quality warnings as far away as the Carolinas in the U.S. and even in Norway.

Nova Scotia has already had two devastating fires that have caused as-yet-uncalculated human suffering and damage — one in Tantallon in suburban Halifax, and the largest in the province’s recorded history in Shelburne County, which as of June 11 had burned 235 square kilometres.

Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre Inc. (CIFFC) showing active wildfires in Canada as of June 9, 2023 Credit: CIFFC

“What’s really changed is the condition of our forest,” Prest tells me. “It’s no longer diverse.”

“Our original forest was probably mostly mixed. It tended towards a softwood mix in some areas, and to hardwood mix in others,” Prest explains. Prior to European settlement, he says Wabanaki-Acadian forests would have good canopy coverage, and underneath the canopy it would be generally damp most of the time, without a lot of sunlight getting through to the forest floor.

“And that in itself would be what would stop the fires from either starting or being widespread,” Prest says. “Certainly, the forest has changed.”

But in Prest’s view, while changes to the forests are certainly not helping reduce forest fire risk, those changes are not the primary cause — climate change is.

Prest says his woodlots, where he has been working hard to restore healthy species diversity and multi-aged forest for decades, have been hit hard by the hurricanes that are increasing in intensity and striking the province more often as the climate changes.

Prest has also started worrying more about fire because of the changing climate.

“I was concerned about the fire situation through the months of April and May,” he says. There was no snow to speak of during the winter, no ice on the lakes around Mooseland, and by the spring, when there should have been a thaw and high levels in rivers, the water levels were down.

“As May went on, it was getting pretty concerning,” Prest says.

“Fire would be much more of a disaster for me than even Hurricane Fiona and Dorian and Juan,” he says. Those windstorms wreaked havoc on the diverse and uneven-aged stands Prest had been allowing to regenerate and nurturing for decades.

“All my work for 40 years making it uneven-aged, with more and more valuable species, is sort of for naught.”

“Our forest structure is going to be very different in the future because of the change in climate, and because oceans are warmer, and probably going to get even more so,” Prest says. “There’s no reason for any of us to think this isn’t going to get worse.”

Wade Prest with his granddaugher Grace Henry some years ago in his woodlot in Mooseland, Nova Scotia. Credit: Laura Henry

With climate change, every forest is at risk

Prest doesn’t think even a healthy diverse Wabanaki-Acadian forest can cope with the kind of extreme weather events and droughts that climate change brings.

He explains that if the woods are too dry, an uneven-aged tree stand that has softwood in the understorey or mid-storey is susceptible to fire because the spruce and fir species constitute a “ladder fuel.”

“They enable a ground fire to get carried up into the canopy to become a crown fire,” Prest says.

Nor does he think lots of deciduous broad-leaf species such as maple and birch in a stand can protect it from fire with the extreme conditions climate change brings.

“Hardwood leaf litter dries out when the spring is dry as we had throughout April and then through May,” Prest says. And the leaf litter on the forest floor becomes “very flammable.”

“I’ve always been critical of industrial forestry practices, and have vigorously promoted the natural Acadian forest as a model for ecological, social, and economic sustainability for Nova Scotia,” Prest says.

He adds:

Now that we seem to have entered a time of accelerated climate change, manifested as more frequent and stronger wind disturbance, and perhaps an altered fire regim, we have to recognize that the Acadian forest has changed, is changing, will continue to change…I was always fond of telling woodlot owners that we had lots to learn about forests, but I honestly didn’t expect a disruption of this magnitude…Having finally succeeded in establishing “ecological forestry” as a legitimate concept, we now scramble to understand and adapt to a new and uncertain climate regime.

However, Prest cautions:

Unfortunately, you’ve got to be careful with that because it just makes a reason for the forest industry to say, “Well we should just harvest on short rotations, so we don’t lose our investment.” And that’s not what we want because it’s so ecologically improper, and I think we as a society understand all the values of the forests.

Prest says he wishes Nova Scotians would make forestry practices a voting issue, so that political leaders might finally “get an upper hand on the forest industry.”

A price on carbon

Since 1967, the year the pulp mill in Pictou opened, the provincial government has handed Forest Nova Scotia (formerly Forest Products Association of Nova Scotia) many millions of dollars to administer forest access road costs. Unbeknownst to many Nova Scotians, those dollars from the gas taxes they pay at the pump.

The “gas tax access program” is a sweet deal for Forest Nova Scotia, as the Examiner reported here. If small operators and woodlot owners wish to benefit from the program, they have to join Forest Nova Scotia, and in turn Forest Nova Scotia can claim to represent the whole forestry sector.

Prest tells me that since 1969, the Nova Scotia Woodlot Owners and Operators Association has been asking the province for a similar road access program for woodlot owners. Their efforts have been in vain.

Prest bemoans the fact that people resist the carbon tax, designed to make gasoline more expensive, which he points out is “the whole idea,” so it will reduce fossil fuel burning and greenhouse gas emissions.

He is referring to the federal government’s pollution pricing plan to combat climate change, which will start in Nova Scotia in July this year. The program raises prices for fossil fuels, but involves rebates to low- and middle-income families that typically exceed what they paid in higher fuel costs.

Prest worries that the majority of Canadians don’t understand that “we need to have a carbon tax, and why.”

Prest recalls the description by Joseph Howe of that tall, diverse and moist forest he walked through in July 1860, and how those qualities would help make the forest “fireproofed” to some extent.

But with climate change, Prest says, no forest is fireproof. “We’ve got a problem we haven’t faced before,” he says.

Wabanaki-Acadian forest one of world’s most diverse

Jamie Simpson is an environmental lawyer, a professional forester and woodlot owner, and the author of three books on forests in the Maritimes.

In an interview, Simpson says a corner of his 80-acre woodlot near Saint Andrews in New Brunswick was scorched by the recent forest fire that burned 1,300 acres in the area, started by a burning all-terrain vehicle.

Simpson’s woodlot was spared more harm only because of the “luck of the wind.”

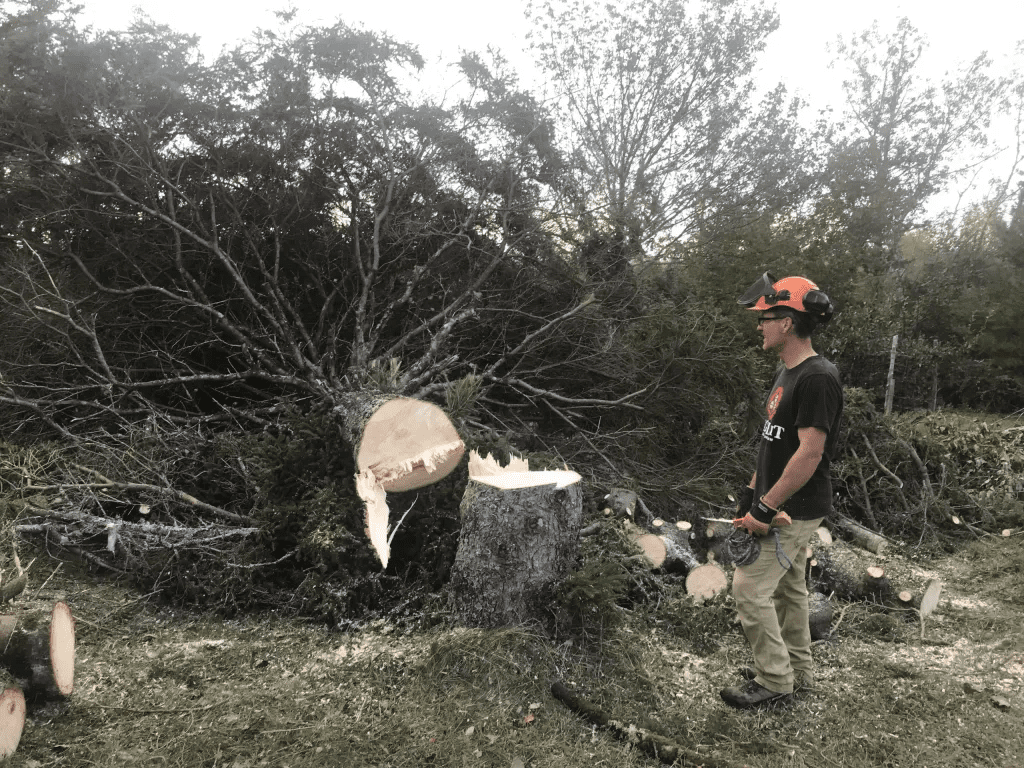

Jamie Simpson is also an arborist, and after Post-tropical Storm Fiona he helped many people clean up fallen trees, or fell trees uprooted or weakened by the wind, as was this white spruce. Credit: Joan Baxter

Simpson has been concerned for years about the health of Wabanaki-Acadian forests in eastern North America and how they will be affected by climate change, interested in how they can also help mitigate climate change.

In his 2014 book Journeys through eastern old-growth forests Simpson writes that old growth forest generally has a tall and largely unbroken canopy, except for occasional gaps caused by the deaths of scattered trees. Today there are only scattered remnants of old growth standing in the Maritimes, representing just 1% of original extent.

“The best insurance against climate change is to encourage and conserve natural forest diversity, especially that found in old forests,” he wrote.

In another of his books, Restoring the Acadian forest, Simpson describes the Wabanaki-Acadian forest, which covers the Maritimes and extends into Maine and Quebec, as:

… an area of transition between two larger forest ecosystems, the Northern Hardwood Forest to the south and the Boreal Forest to the north. As such, the Acadian Forest combines elements from each of these forests, creating a blend of softwood and hardwood trees (32 species in all) found nowhere else. In its natural state, the Acadian Forest is one of the most richly diverse temperate forests in the world.

Simpson tells me that forest practices such as clearcutting and “anything that results in a preponderance of young and even-aged forests” can make forests more susceptible to forest fires and pests, both of which climate change exacerbate.

He says such forest practices “tend to encourage more conifers, for a more boreal-type forest,” with an overabundance of fir and white spruce.

Says Simpson:

When you have a lot of conifers growing and they’re young to middle age, up to say 40 or 50 years old, in that sort of stage of their life they tend to be more vulnerable to forest fires. And that’s the condition that we’ve created across a lot of the Maritimes … partially through forestry practices, but also just simply through land clearing for agriculture and then allowing that land to grow up in forests, typically with white spruce.

‘Human-driven disasters’

Mike Lancaster, coordinator of the Healthy Forest Coalition in Nova Scotia, lives close enough to the fires in Halifax that he was in the “yellow alert zone.” For a week while the fires raged, he was prepared to be evacuated.

In an interview, Lancaster tells me he was not surprised by the forest fires, but he was surprised by how quickly they spread, and by some people’s lack of awareness of fire risks and the disregard for fire bans.

He says he falls into a “small demographic that is pretty much always happy when it’s raining.”

“I’m always particularly elated when it rains during holidays because that’s usually the highest risk time,” Lancaster says. “People are lighting off fireworks, which I think very few people associate with a large risk of wildfire. But it is. Just like campfires.”

“It doesn’t really matter if there’s a fire ban on the Canada Day or Natal Day or Labour Day weekends,” Lancaster says. “If it’s a nice weekend, it’s pretty hard to avoid. There will be a fire … whether or not there is a fire ban.”

Lancaster notes that both the Halifax and Shelburne fires were human caused, and that climate change is also a component.

“So these are definitely human-driven disasters,” he says.

According to Lancaster:

One of the greatest defences that we have against fire risk is diversity … not just of species composition but also age and physical attributes. Natural Wabanaki-Acadian forests are composed of a mosaic of gaps that have been established over centuries, which means our forests have evolved a built-in reduction of fire risk.

He notes that after World War II and the Vietnam War, there was an explosion in the development of herbicides that were used to kill off deciduous species and manage forests for softwood species industry was looking for.

“It is widely known that conifer forests present a greater forest fire risk than those which are deciduous dominant,” Lancaster says. Because the forestry industry in Nova Scotia has historically been geared to favour coniferous species, in his view, “That translates as an increased forest fire hazard

Lancaster believes we need to do better in quantifying and appreciating the full ecological and economic value of forests, given the incalculable costs of the wildfires not just in monetary terms, but also human and ecological ones. He adds:

I don’t even really have much of an understanding of just how much these fires are going to cost in terms of the firefighting efforts and the subsequent damages, but I’m assuming it’ll be an excess of a billion dollars.That’s about as far as my mind can wrap around it. But it’s got to be a staggering number … if we continue down the path that we have been going, then we’re not doing justice to our society and our citizenry and, you know, not assigning the true value and the true costs to that inaction [to reduce fire and climate change risk] or a continued action that accelerates their impacts.

Lancaster concludes:

We need to we need to fully embrace how forestry plays a part, both in increasing the [fire] risk and how it can play a part in reducing risk too, because that needs to be a component of the discussion. Forestry writ large can be used, through silviculture methodology, to eliminate plantations, and to re-naturalize, and … to convert plantations back into natural forest ecosystems that have a greater level of diversity.

Citizen scientists doing their biodiversity survey in forests near Goldsmith Lake, Nova Scotia. Credit: Nina Newington

Diverse forests store more carbon

Anthony Taylor is an associate professor of forest management at the University of New Brunswick who hails from the Musquodoboit Valley in Nova Scotia.

In 2020, Taylor was the lead author of a review of natural disturbances in Nova Scotia’s forests, which aimed to help inform the implementation of ecological forestry in the province to restore “forests to a more natural, pre-settlement state.” The authors looked at 300 years of data, Taylor says in an interview.

“What we found through that work was that the three biggest natural disturbances by far that affect the forests of Nova Scotia historically would be wind (tropical storms), spruce budworm, which is a natural insect in the forest here, but also fire being the other one.”[1]

“Forest management practices during the 20th century and up to today have contributed to a younger Acadian forest and one with a higher abundance of spruce and fir,” Taylor says. “But it’s really tricky to say by how much as we have poor data on what the baseline pre-European settlement forest was like.”

Taylor sees tree diversity as important in mitigating climate change. He is co-author of a recent paper published in Nature, which shows “conserving and promoting functionally diverse forests” promotes storage of carbon and nitrogen. That means the benefits are two-fold; a balanced mix of trees in a forest keeps more carbon in the ground and also increases soil fertility.

Anthony Taylor Credit: contributed

In an interview, Taylor explains that monoculture plantations or tree stands with fewer species are less effective at sequestering carbon in the soil than systems where there are multiple species interacting together.

Just as a smart investor reduces risk with a diverse portfolio, Taylor explains, a diverse and ecosystem is also more robust and less susceptible to disturbances like fire.

Taylor says maintaining tree diversity can also help reduce forest fire risks to some extent. “All forest will burn if the weather is dry enough, but most hardwood species and hardwood stands tend to be less flammable, so having mixed-wood and hardwood stands on the landscape is important.”

Still, Taylor believes the primary factor making forests vulnerable to fire is climate change, and just having a mixed forest with hardwoods and softwoods is not enough:

Having a mixture of species where some species are less susceptible to fire, species that are less flammable, for instance, is a strategy that could help. But there also comes a point when, if the climate warms enough that it doesn’t matter what the species composition is, if you get enough dry days in a row and you have ignition, even those less flammable species like the some of the birches and maples will still burn, as happened in Nova Scotia. The fires outside Hammonds Plains or even down in Shelburne were not just spruce and fir forest. There was a lot of mixed wood and hardwood content there. And so they could burn as well.

99% of forest fires in NS are human-caused

“We know a certain amount of climate change is going to take place no matter what,” Taylor says. “In this region, the average annual temperature is expected to warm a couple of degrees in the next 30 years.”

Given that bleak reality, Taylor has some other suggestions for reducing forest fire risks.

“Besides stopping climate change, the next biggest thing is becoming much more aware of our role in starting fires,” Taylor says. “We have so much more access to the forest than we ever had, largely through all terrain vehicles and that sort of thing.”

Taylor says the data for the past century show less than 1% of all fire ignitions in Nova Scotia are naturally caused by lightning. That means 99% are caused by humans.

More complex than rocket science

Taylor observes that there is also some debate around how Canada reports its annual greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) and how forest fires figure into that reporting.

As the Examiner reported here, a recent report by NRDC and Nature Canada criticized the Canadian government policy for not reporting emissions released by forest fires — 287 megatonnes in 2021 — because it considers forest fires to be “out of control of human activity,” while the GHG reporting is meant to count human-caused GHG emissions.

“When you have a record fire year like we’ve just had here so far in Canada … then that all represents a net source of carbon into the atmosphere,” says Taylor.

“To regain all that carbon, you have to wait for all those forests to grow again,” Taylor notes.

He acknowledges that the whole issue of how forests can mitigate climate change, and how they are also being affected by climate change is “very complex.”

“I like to say it’s not rocket science, it’s much more complex than that.”

After the interview Taylor sent me an email to sum up his thoughts on the subject.

“Climate change is going to increase the probability of forest fire in Nova Scotia, since a warming climate will increase the likelihood of severe fire weather days,” he wrote.

Topping his list of ways to combat the forest fire risk, he reiterated: “Stop climate change.”

By Joan Baxter

This article was orginally published in the Halifax Examiner. See the original article here.